Lecture 7: Chromatic Adaptation

- Discuss the importance of light in photosynthesis and the different types of pigments involved.

- Explain the concept of light compensation point and light saturation point.

The lecture will focus on the importance of light for photosynthesis, exploring the different types of pigments involved and physiological concepts such as the light compensation point and light saturation point.

- Saffo, M. B. (1987). New light on seaweeds. Bioscience, 37(9), 654-664.

- Ramus, J., Beale, S. I., & Mauzerall, D. (1976). Correlation of changes in pigment content with photosynthetic capacity of seaweeds as a function of water depth. Marine Biology, 37(3), 231-238.

- Ramus, J., Beale, S. I., Mauzerall, D., & Howard, K. L. (1976). Changes in photosynthetic pigment concentration in seaweeds as a function of water depth. Marine Biology, 37(3), 223-229.

1 Introduction: Development of the Theory of Chromatic Adaptation

Welcome back again. Today, we are going to be talking about the development of the theory of chromatic adaptation. This is an interesting story that offers insight into how science evolves, and it demonstrates that over a span of about

Let us explore some of the key contributors to our theories surrounding chromatic adaptation.

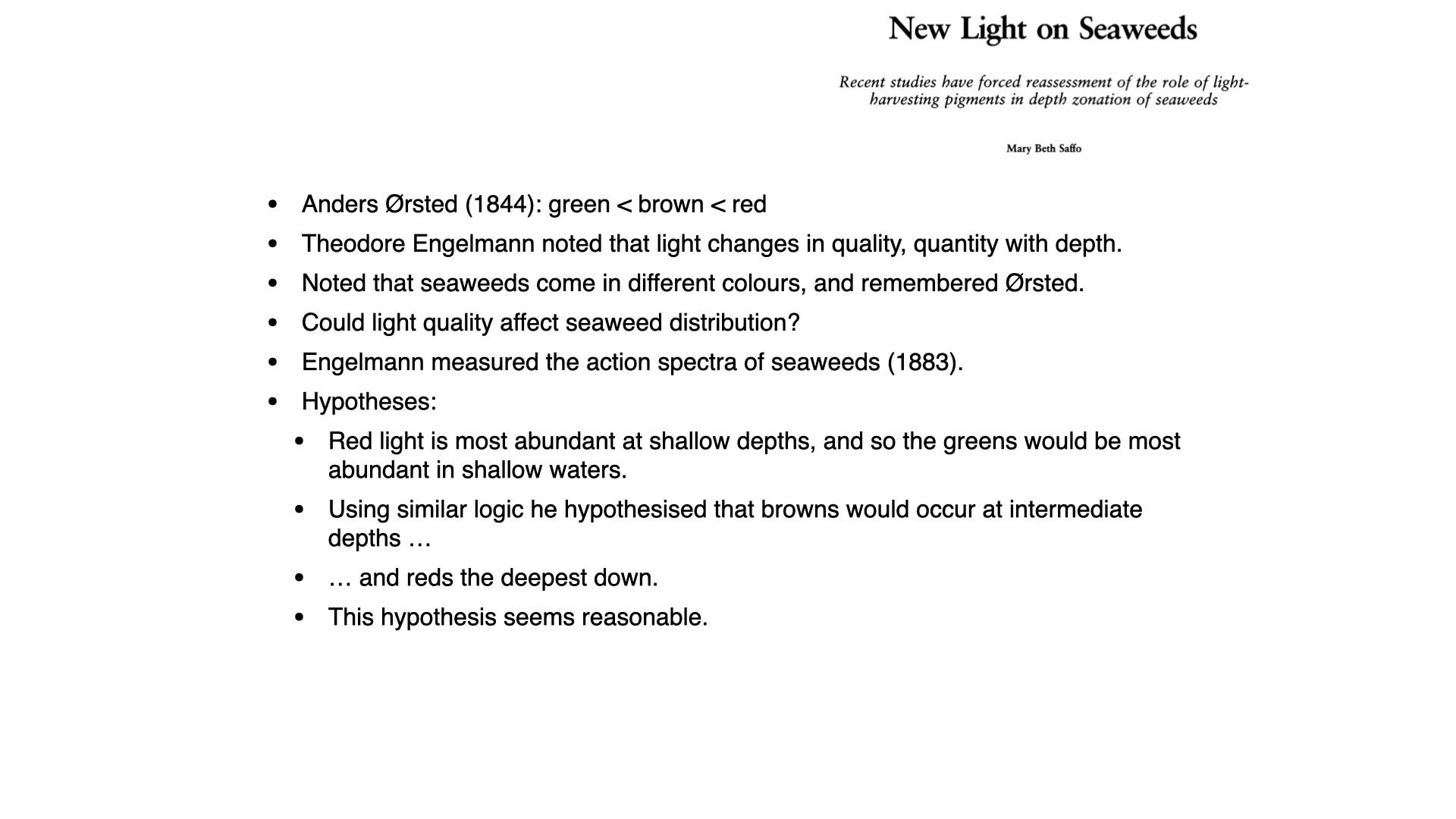

2 Early Observations: Anders ØRsted

The story begins in the mid-19th century with Anders Ørsted. In

3 Theodor Engelmann and Chromatic Adaptation Theory

Building on Ørsted’s observations, Theodor Engelmann published his theories around

On paper, this seems a reasonable hypothesis — even today, many might formulate similar conjectures without access to contemporary evidence. Engelmann sought to test this hypothesis experimentally.

4 Engelmann’s Experimental Design

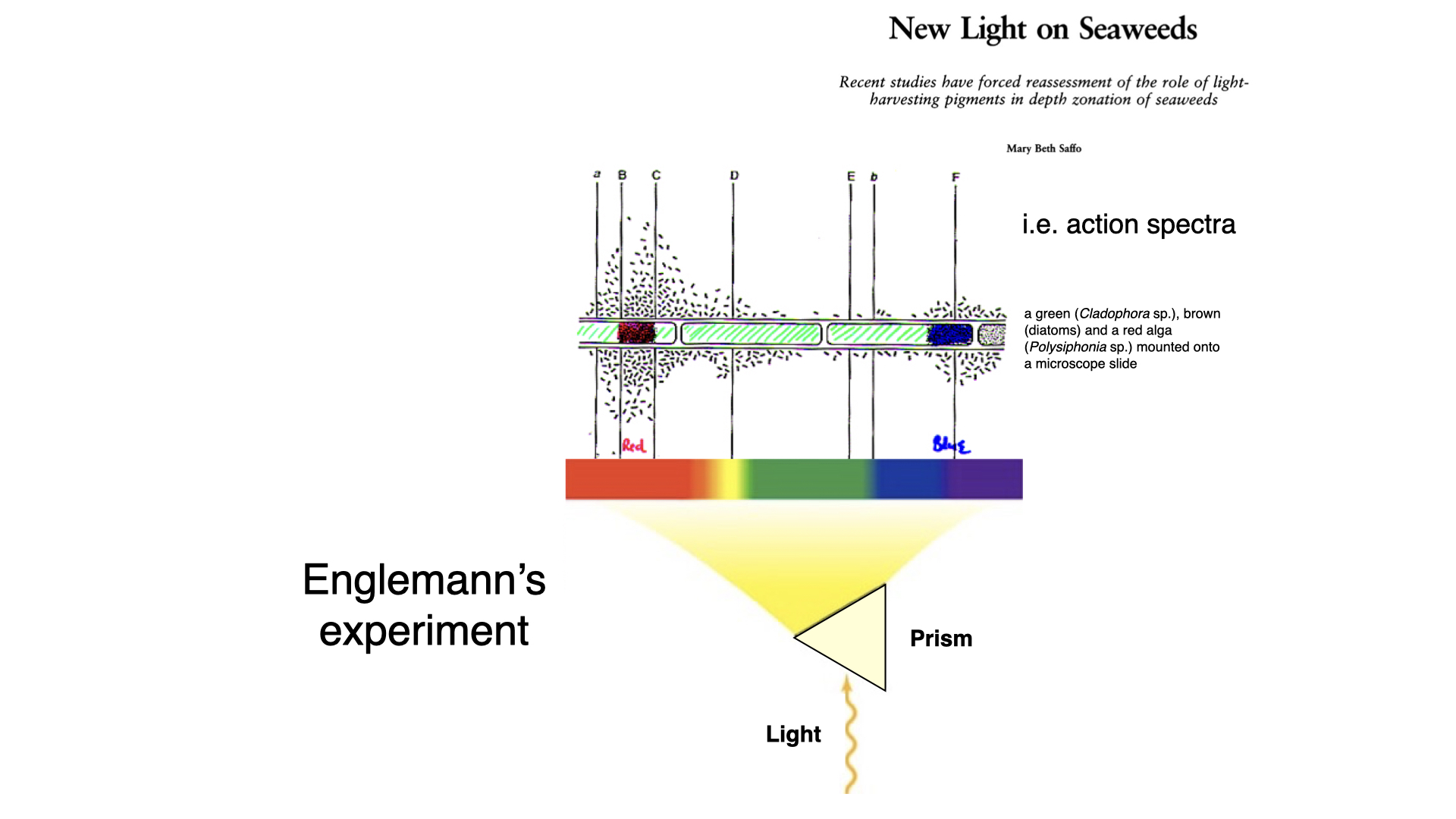

Engelmann’s clever experiment utilised a prism, constructed by Carl Zeiss — a leading figure in optics at the time. Zeiss’s company, known for its lenses and microscopes, continues to exist. Engelmann used the prism to split white light into its constituent spectral colours, ranging from red to blue, which he then projected onto a microscope slide.

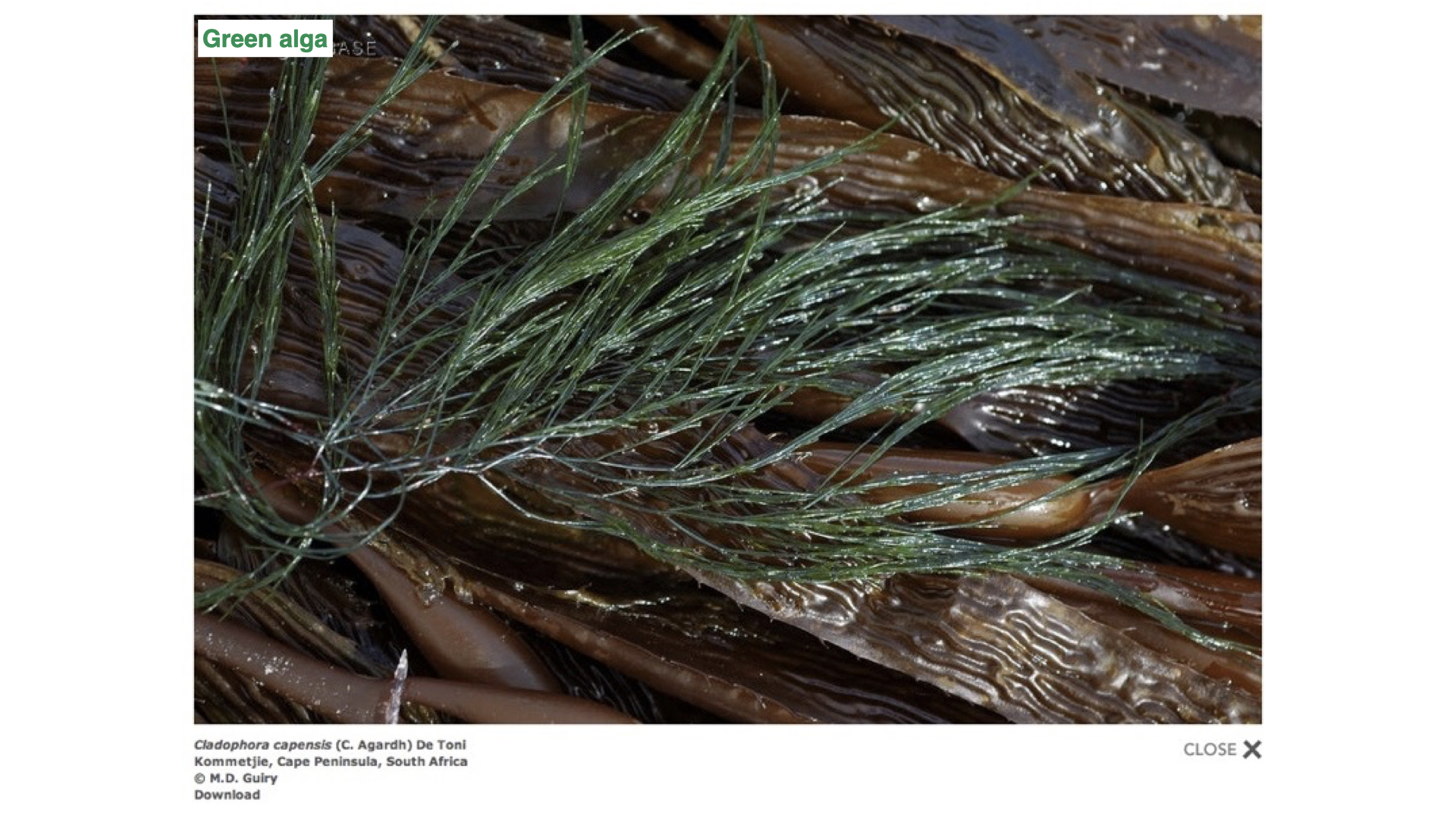

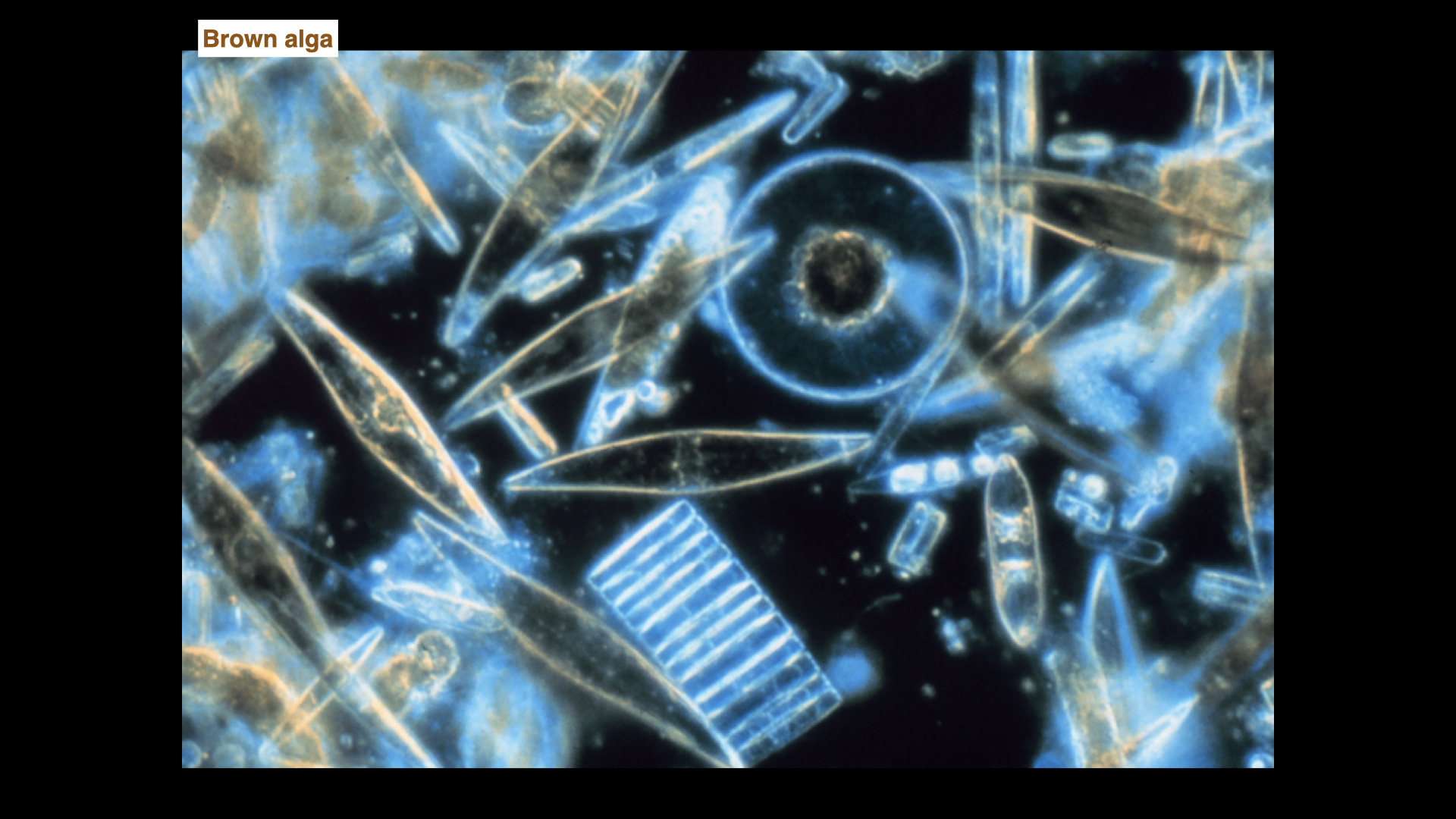

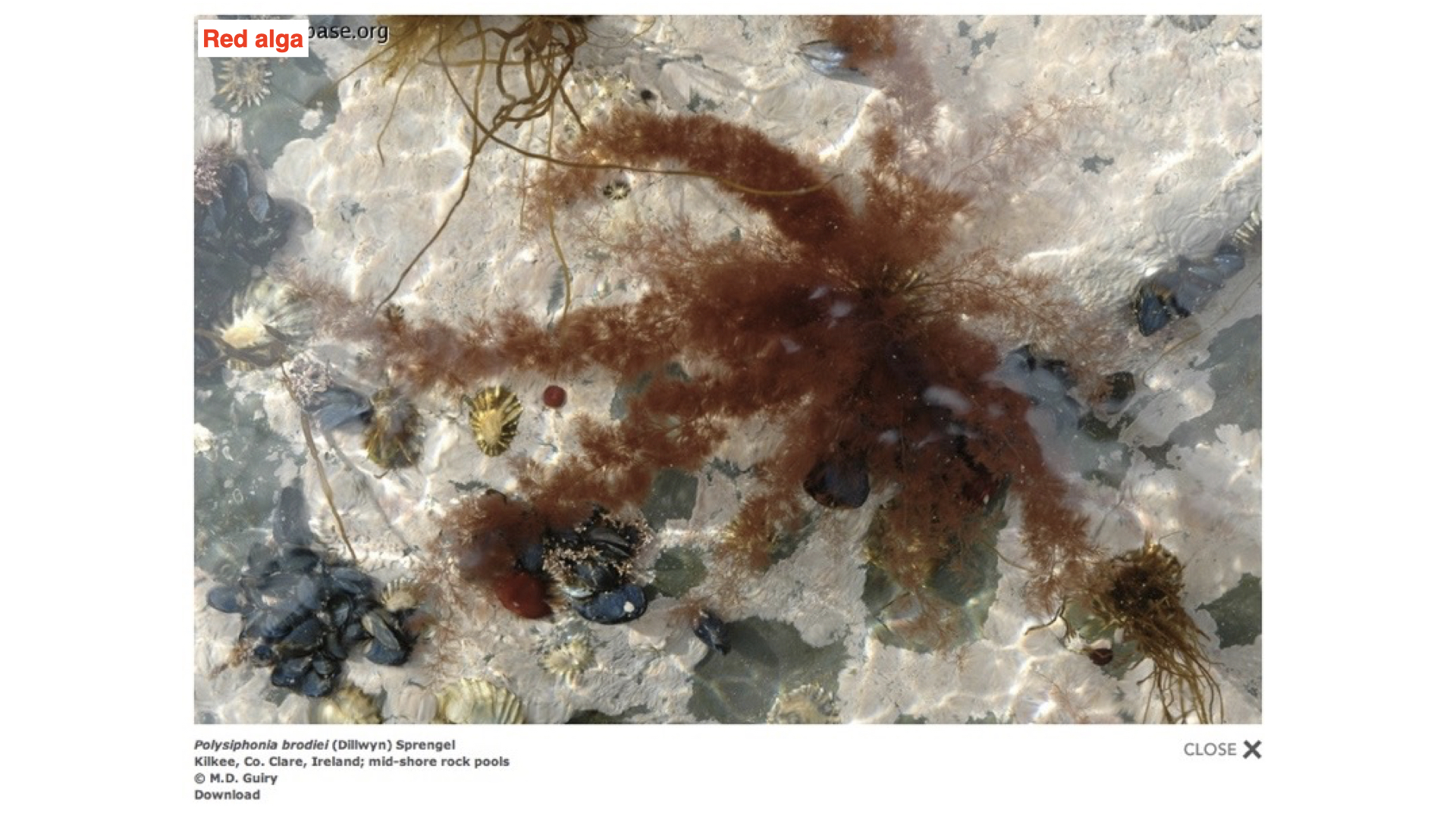

On this slide, along the gradient of coloured light, he positioned different algae: a green alga (for example, Cladophora, though Engelmann used a species within this genus), a brown alga (unicellular diatoms, known for their xanthophyll pigments and golden-brown hue), and a red alga (such as the filamentous Polysiphonia, which contains phycobiliproteins like phycocyanin and phycoerythrin).

In the watery medium surrounding the algae, Engelmann introduced aerotactic bacteria — organisms attracted to regions with the highest oxygen concentration. The premise was that as each type of alga was exposed to a spectrum of light, photosynthesis would occur most efficiently at wavelengths suited to its pigments. The bacteria would congregate where oxygen (a byproduct of photosynthesis) was produced most abundantly, thereby indicating which regions of the light spectrum promoted photosynthesis for each algal type.

4.1 Action spectrum demonstration

Engelmann observed, for example, that in green algae — containing primarily chlorophyll-a (and to a lesser extent, chlorophyll-b)—the bacteria accumulated at two main peaks along the slide: those corresponding to red and blue light. This demonstrated, for the first time, an action spectrum — the relationship between wavelength and photosynthetic activity — though Engelmann did not yet reference absorption spectra (as you will see later with the work of Haxo and Blinks).

He also performed this experiment with brown algae and red algae. In these cases, thanks to their accessory pigments (xanthophylls in browns, phycobilins in reds), photosynthesis also occurred in the green gap region where chlorophyll-a is ineffective. Bacteria correspondingly accumulated in the wavelengths that these accessory pigments absorb.

5 Implications and Predictions

Engelmann’s results seemed to experimentally confirm Ørsted’s reasoning from

He reasoned that brown algae, with their ability to exploit greenish wavelengths due to xanthophylls, would be most successful at intermediate depths. Meanwhile, red algae — able to use blue light particularly efficiently — would dominate the deeper ocean, where blue and green light are most available.

At the time, no one had directly surveyed seaweed distribution by colour at different depths, but the experimental and theoretical framework appeared solid. For decades, Engelmann’s work underpinned ecological thinking about seaweed vertical distribution — even as recently as the

6 Moving Forward

As we shall see in the next lecture, later work by Haxo and Blinks provided further evidence for this mode of thinking. However, more recent research began to challenge this story, signalling the emergence of a different understanding — a topic we will discuss in more detail in due course.

7 Revisiting Engelmann’s Work

Continuing with our narrative on chromatic adaptation, let us turn our attention to some of the research undertaken by Haxo and Blinks, which was carried out approximately 50 or 60 years after Engelmann’s initial experiments. They were able to repeat similar experiments to those of Engelmann, but with the benefit of more modern technological advancements. Specifically, they had access to laboratory-built devices capable of precisely generating monochromatic spectra of light.

In their studies, Haxo and Blinks used a variety of red, brown, and green seaweeds — akin to Engelmann’s approach. However, they extended the methodology by examining not only the action spectra, but also the absorption spectra of both intact thalli and pigment extracts from the different seaweeds. As a result, they utilised three distinct lines of evidence in tandem: action spectra, absorption spectra from intact tissue, and spectra from pigment extracts. Engelmann had primarily focused on action spectra, whereas Haxo and Blinks introduced this more differentiated and integrated approach.

Based on their accumulating evidence, they drew several novel conclusions.

8 Green Algae: Action and Absorption Spectra

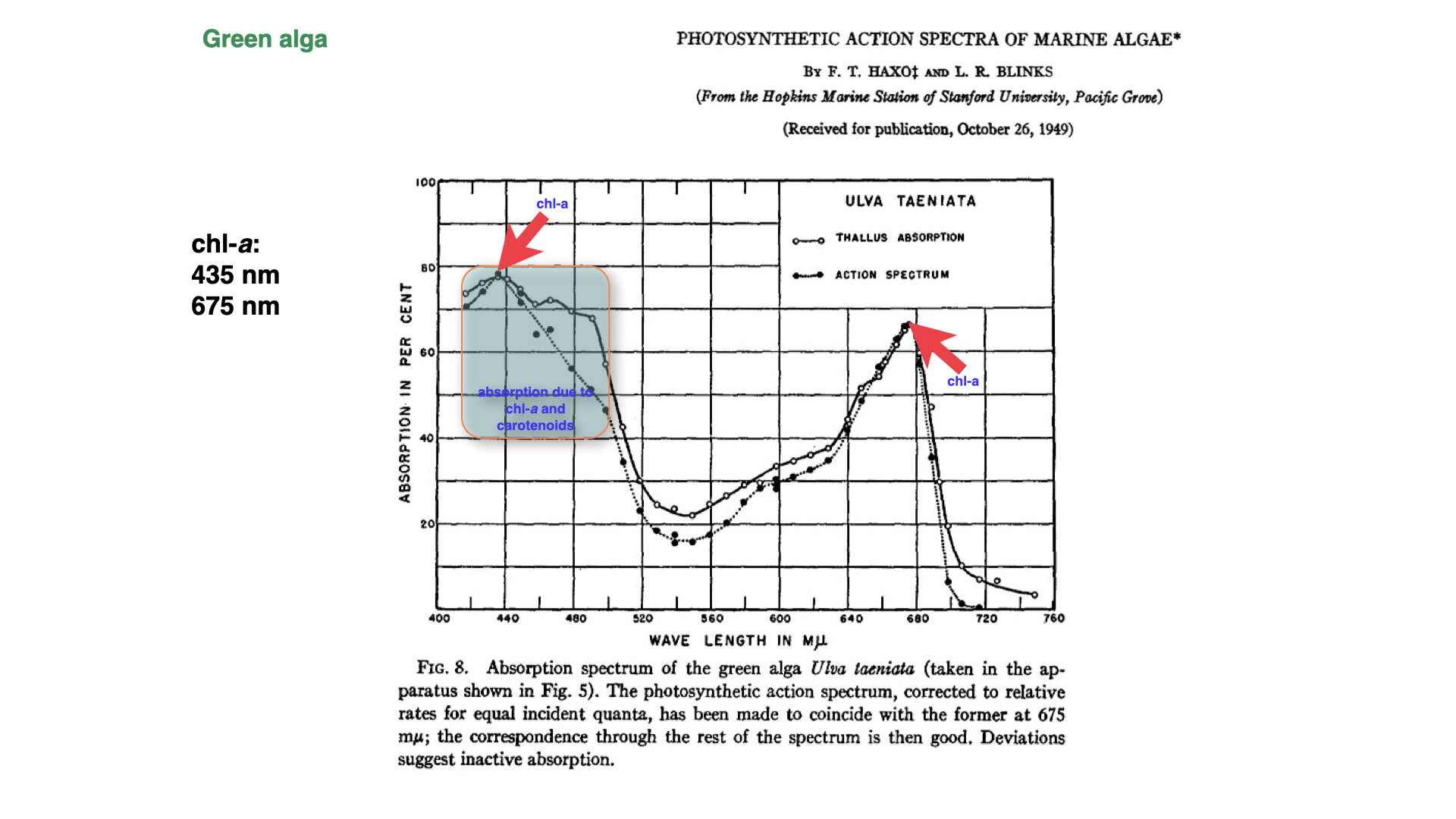

When conducting experiments on green algae, Haxo and Blinks found that the thallus absorbs light most efficiently in the zones of blue light, approximately

Additionally, the absorption spectrum in the thallus matched very closely the action spectrum established for green algae. Whereas Engelmann’s methods relied on the movement of aerotactic bacteria as an indirect measure of photosynthesis, Haxo and Blinks directly measured photosynthetic rates.

For green algae, their findings were represented on a graph: the absorption peak for chlorophyll-a appears in the blue light region, as well as in the red. The solid line, marked with open circles, depicts the absorption spectrum, i.e., the extent to which the thallus absorbs light at the tested wavelengths. The dotted line illustrates the action spectrum — the rate of photosynthesis across those wavelengths. Strikingly, at the peaks of chlorophyll-a absorption — in both the blue and red regions — the action and absorption spectra are almost identical.

However, there exists a significant discrepancy in the region from approximately

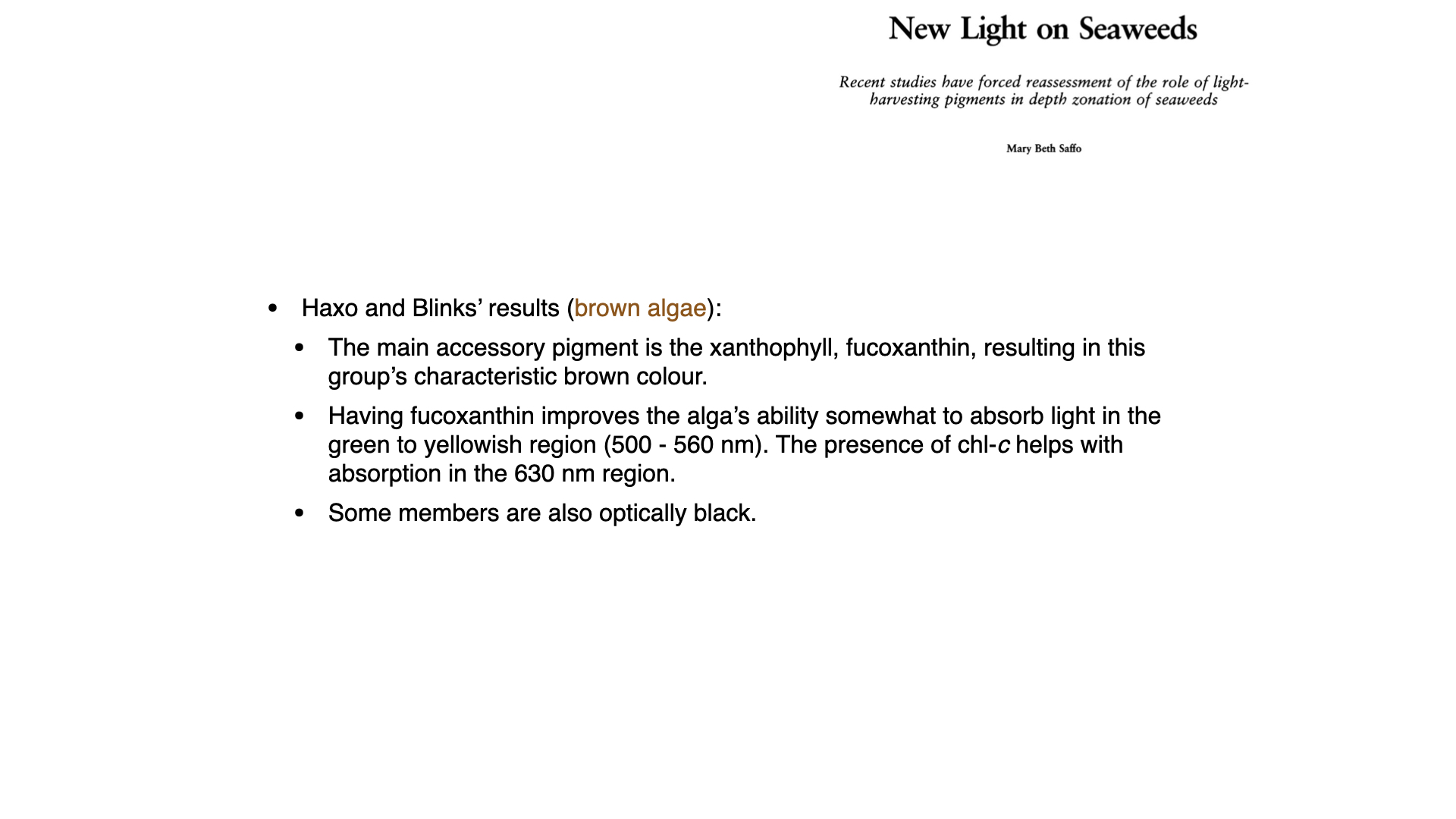

9 The Role of Accessory Pigments in Brown Algae

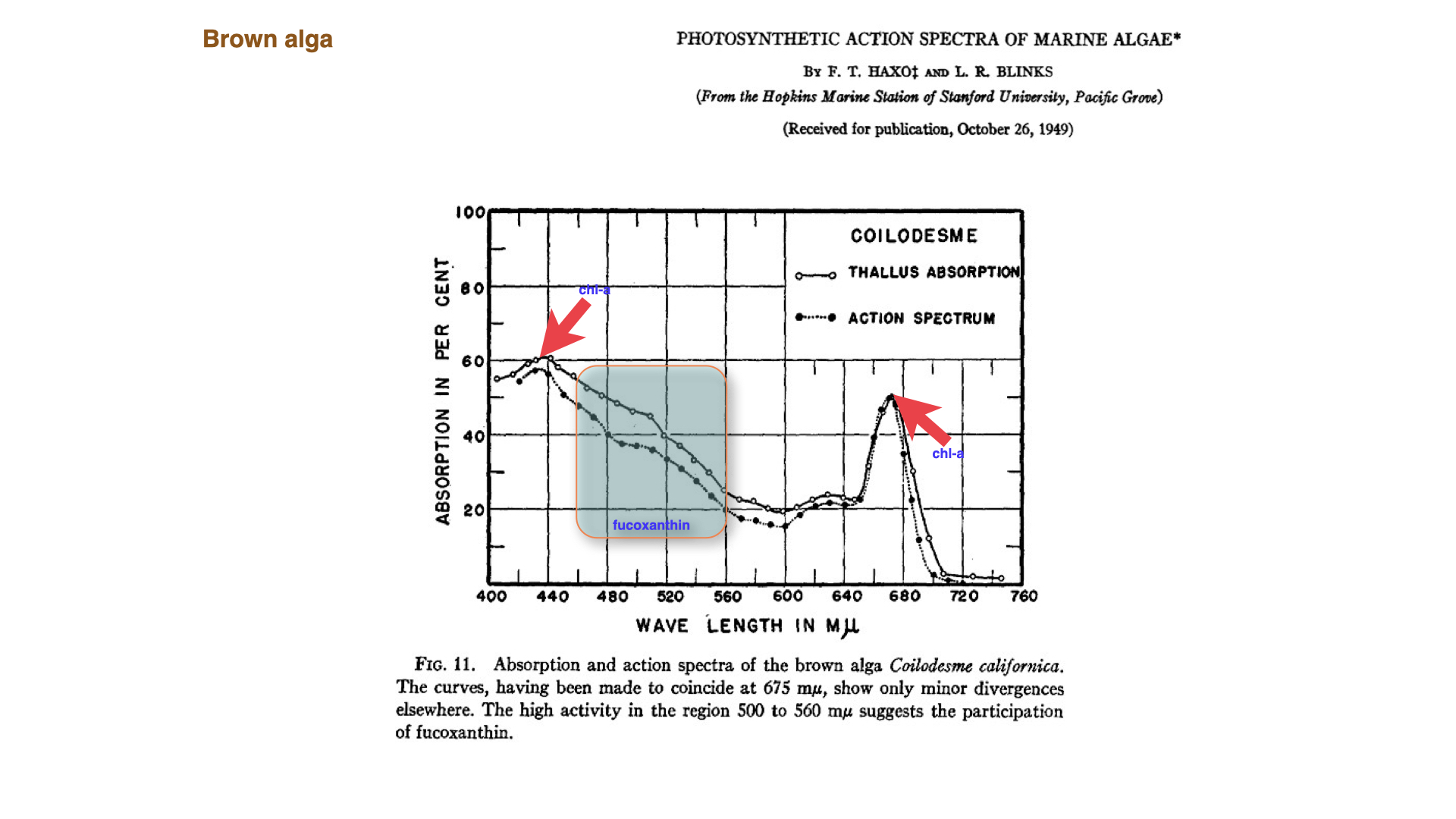

Similar experiments with brown algae showed that the dominant accessory pigments are xanthophylls, particularly fucoxanthin, which give these seaweeds their distinctive colour. Fucoxanthin enhances absorption in the green to yellowish part of the spectrum — between

Some brown algal species accumulate so much chlorophyll-c that they appear almost “optically black,” meaning they are nearly opaque to all light — a phenomenon we will discuss in more detail later.

In summary, peaks persist in both the blue and red regions (where chlorophyll-a absorbs maximally). However, in the so-called “green gap” region — which would otherwise show limited absorption were it not for accessory pigments — the presence of fucoxanthin allows light capture, thereby enabling chlorophyll-a to drive photosynthesis in the green to yellowish region. Xanthophylls, primarily fucoxanthin in this context, expand the functional spectral range available to brown algae.

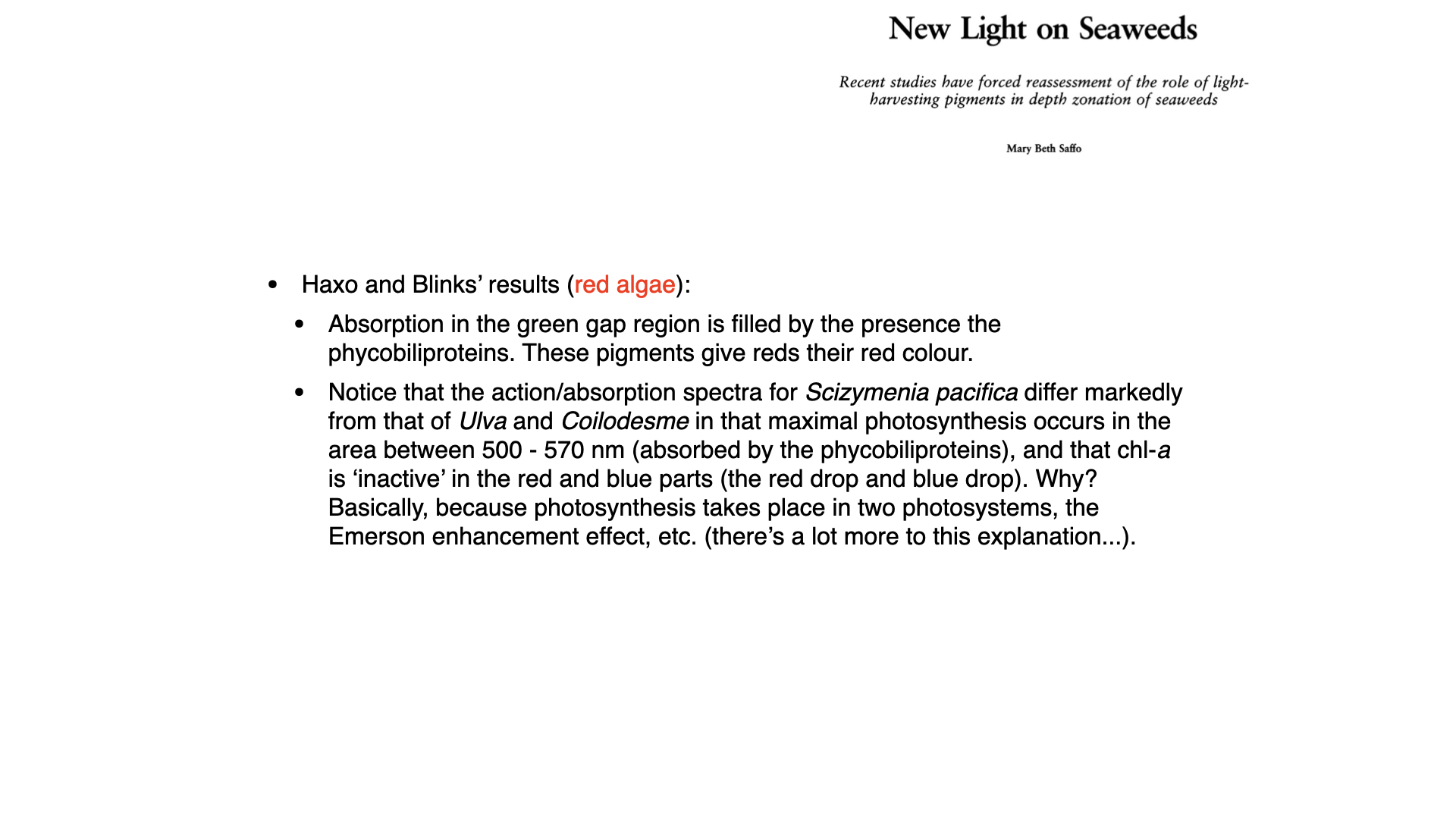

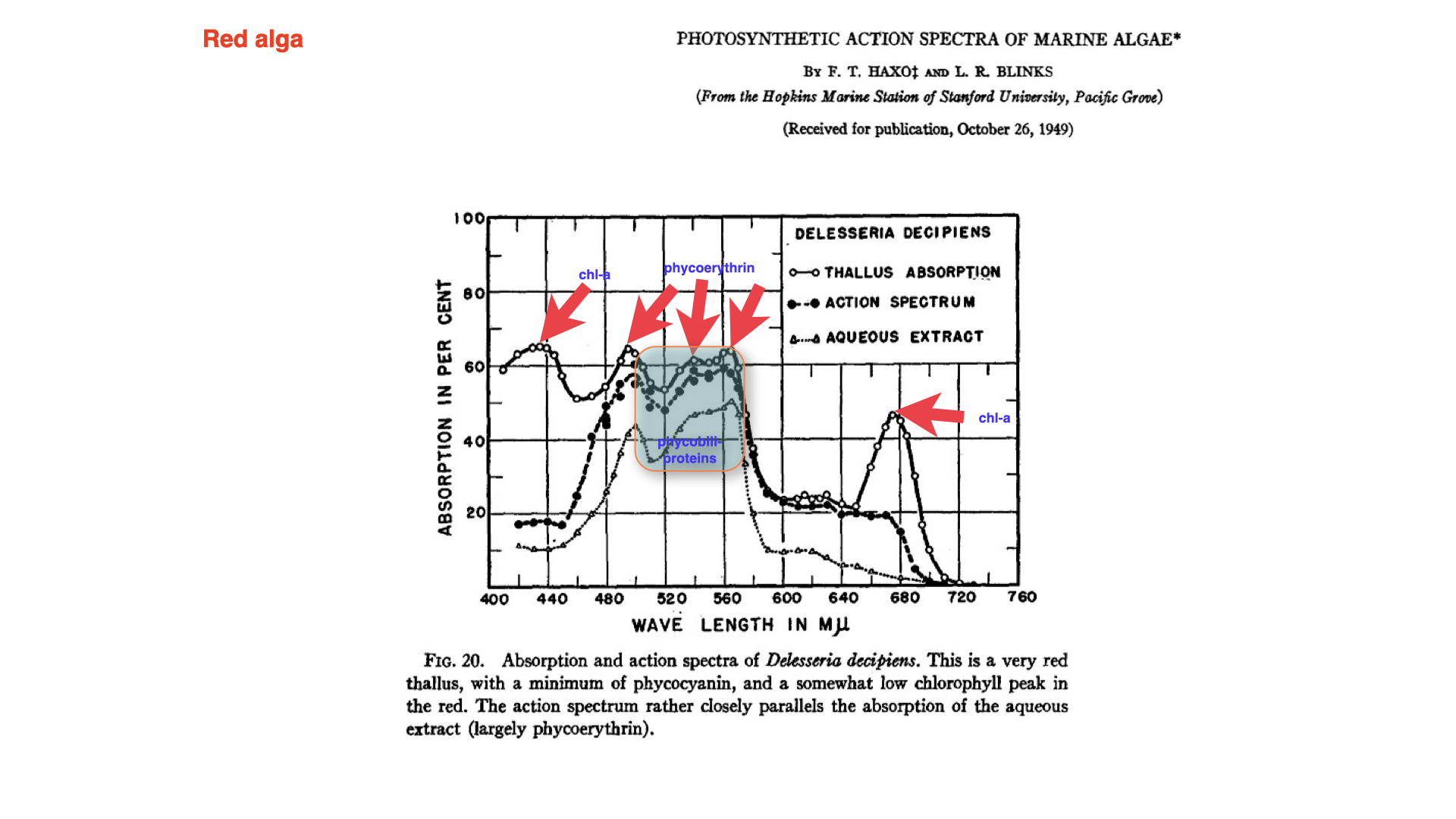

10 Red Algae: Patterns, Anomalies, and the Emerson Enhancement Effect

Red seaweeds demonstrate a broadly similar pattern, with absorption and action spectra matching closely except for a notable anomaly between

Overall, the major divergence between the absorption and action spectra at particular peaks is attributable to this phenomenon. For deeper exploration, seminal literature exists, such as the 1964 publication by Govindjee (often cited simply as “Govindjee”), one of the preeminent figures in photosynthesis research. If you wish to read further on the Emerson enhancement effect, consult works by Rajni Govindjee and Govindjee.

11 From Engelmann to Haxo and Blinks: Confirmation and Caution

Fundamentally, the work of Haxo and Blinks provides modern and more definitive confirmation of Engelmann’s earlier findings, as noted in subsequent review papers by authors such as Mary Beth Saffo . However, the conclusions drawn by Haxo and Blinks are somewhat more measured regarding the vertical distribution of seaweeds.

In the case of red algae, where phycobilins function as accessory pigments, they conclude that it is logical to assume the current vertical distribution of red algae is influenced, at least in part, by the photosynthetic effectiveness conferred by phycobilins. This enables some species to extend their distribution to depths inaccessible to other algae. Essentially, red algae — by virtue of their red pigment, which can absorb blue light — are able to survive further down the water column. Nevertheless, they note that other algal groups, such as greens and browns, are also located at considerable depths, and red algae are present even in shallow waters.

12 Chromatic Adaptation and Vertical Distribution: Theory and Reality

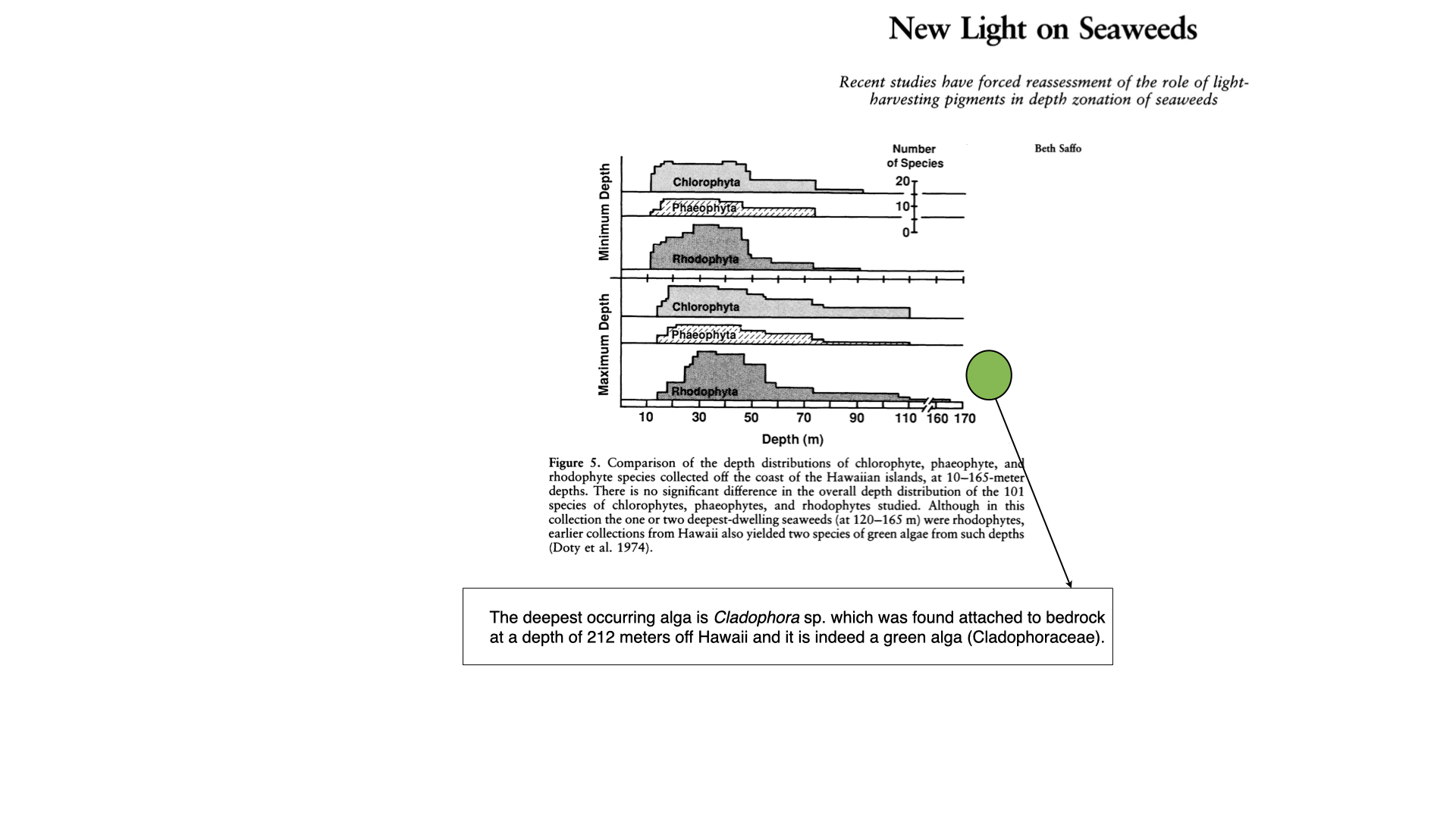

This real-world evidence introduces a measure of doubt to the hypothesis that green algae occupy shallow waters, red algae deep waters, and brown algae intermediate depths. Observational data show substantial overlap among all three groups regarding both minimum and maximum depth ranges. For instance, even though red algae are documented as extending down to roughly

Such empirical data suggest that the theoretical framework of chromatic adaptation — namely, that a seaweed’s pigment determines its depth distribution — does not hold up against actual observations. Instead, pigmentation seems not to be reliably indicative of environment, nor a sole determinant of where a species is found.

13 Towards an Explanation

Thus, the chromatic adaptation theory does not adequately explain the actual vertical distribution of seaweeds. To gain a clearer understanding of what does underlie these patterns, we must examine further research, especially the work of Rosenberg and Ramus, which will form the subject of our next lecture.

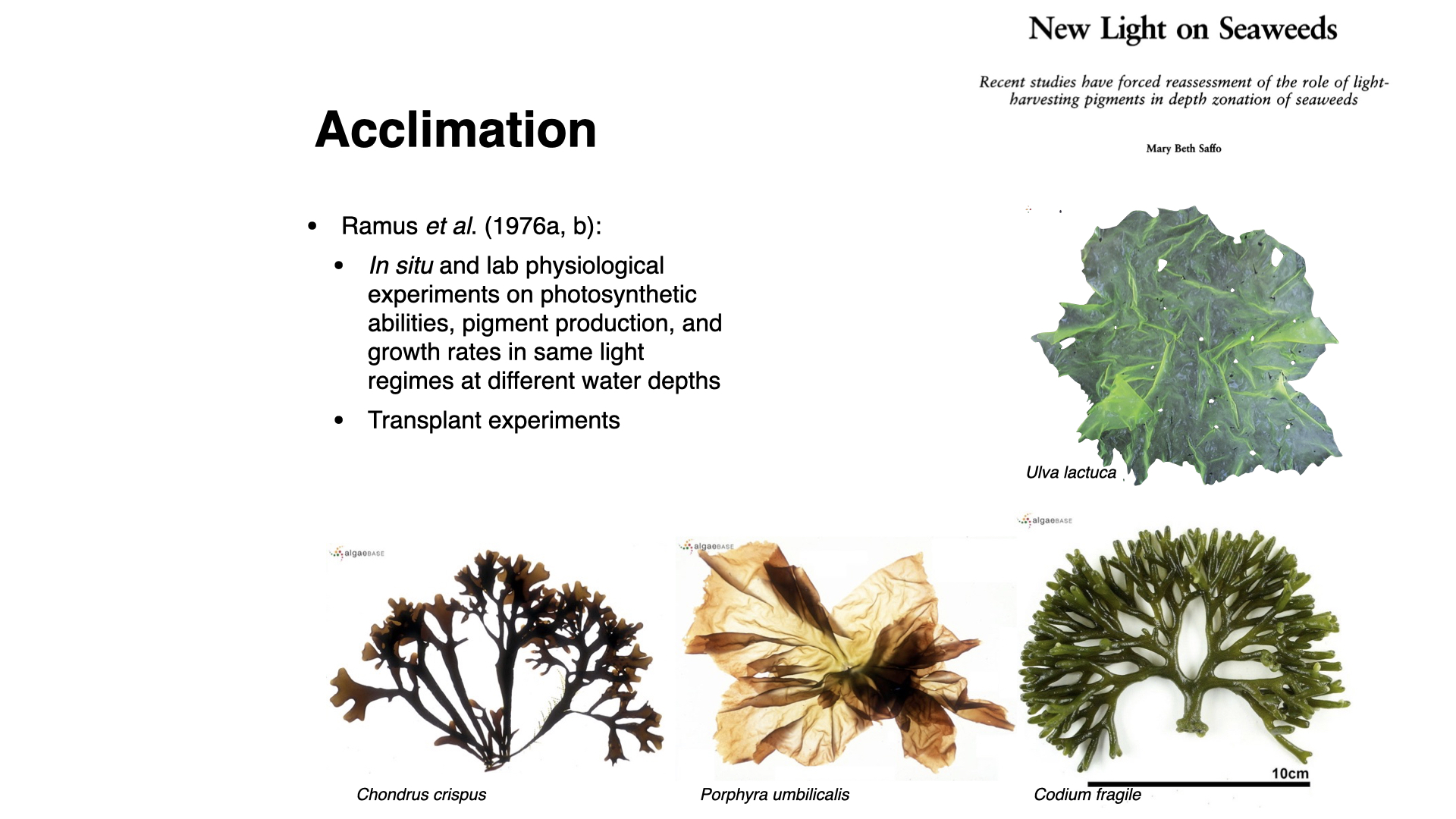

14 In Situ Experiments on Seaweed Acclimatisation

Right, so now we are going to look at the third part of our series of lectures on chromatic adaptation and, this time, we are going to examine some in situ experiments that explore how seaweeds adapt — or more accurately, acclimatise — to different light regimes within the ocean. This is a very different approach compared to the earlier studies by Engelmann, Haxo, and Blinks, all of whom relied on laboratory studies, isolating seaweeds from the ambient environment and failing to explore how they respond adaptively or acclimatise to changing environmental conditions. This is where Rosenberg and Ramus’s work is quite distinct.

Specifically, we will focus on experiments by John Ramus from the late 1970s, which are rather fascinating in their design. Ramus investigated acclimatisation as a process whereby seaweeds, irrespective of their colour, become suited to different light regimes found in the marine environment.

14.1 Experimental design

The method they used was as follows: Seaweeds acclimatised to shallow water — the surface, say, for a couple of weeks, so that their photophysiological machinery and pigment profiles had the chance to adapt — were compared to seaweeds that had, during the same period, been grown in deeper water, at approximately

Noting that seaweeds come in a range of colours, they included red and green seaweed species. The red algae possess phycobilins as accessory pigments, along with some

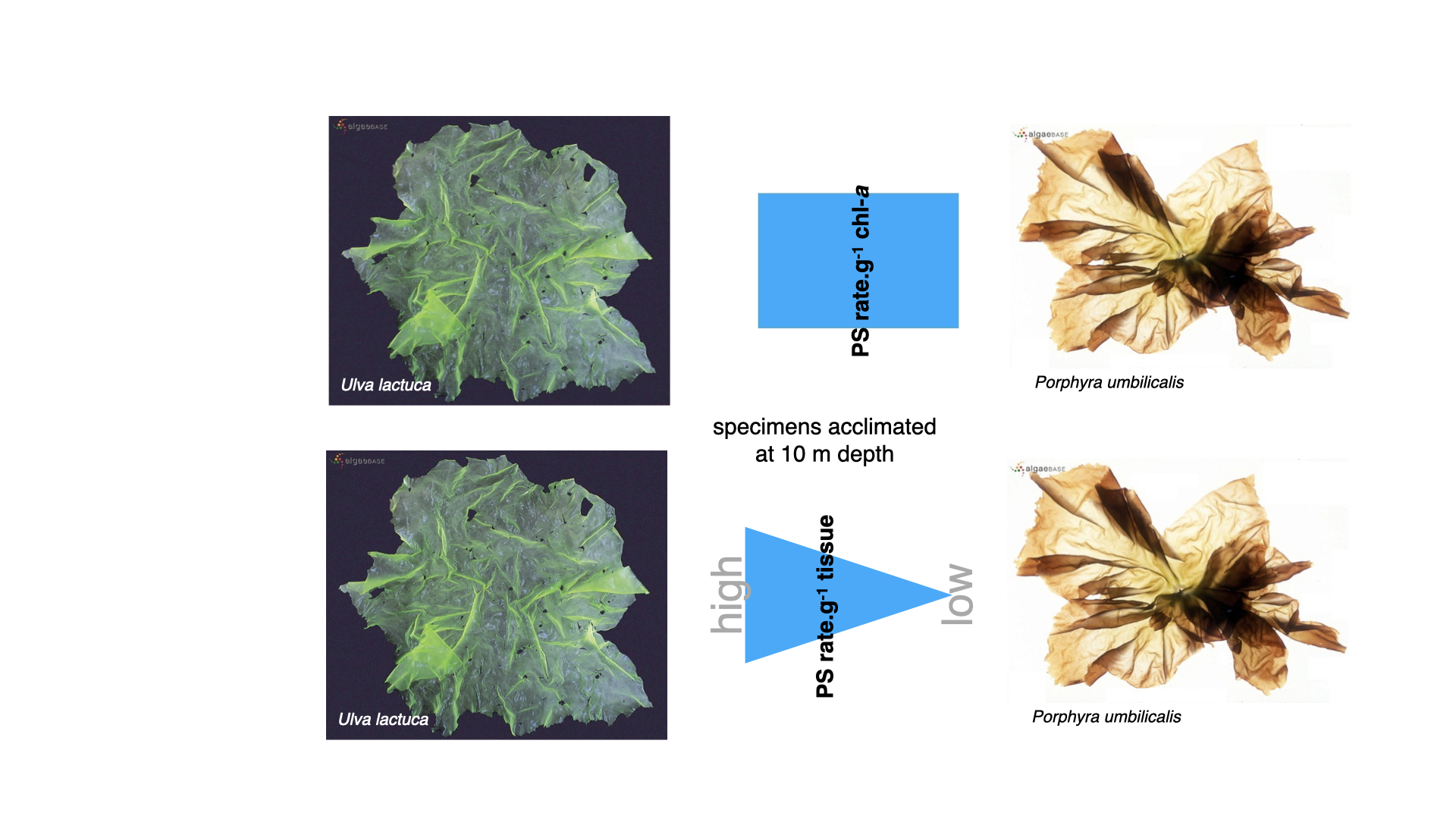

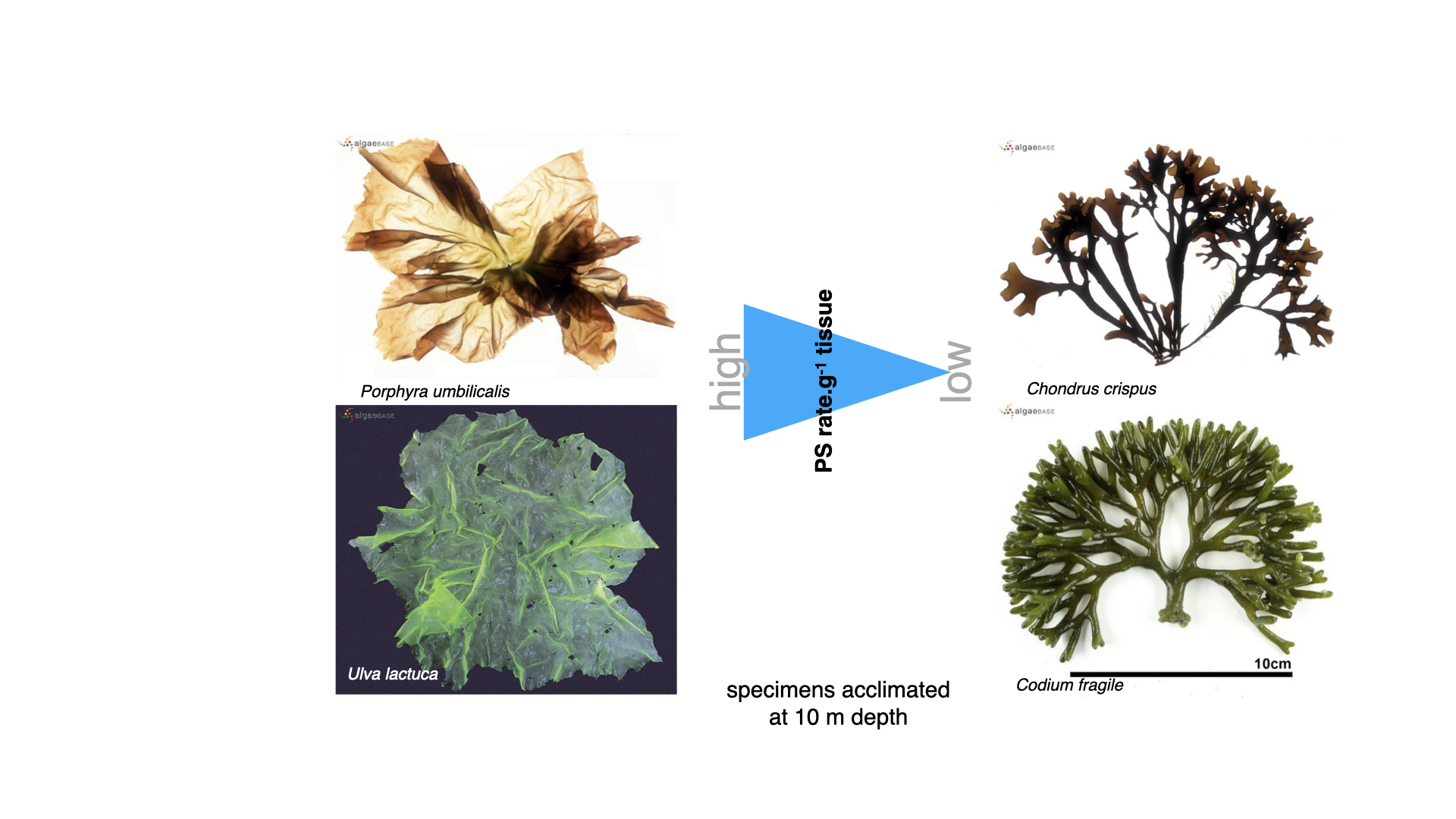

They selected four species:

- Chondrus crispus (red)

- Porphyra umbilicalis (red)

- Codium fragile (green)

- Ulva lactuca (green)

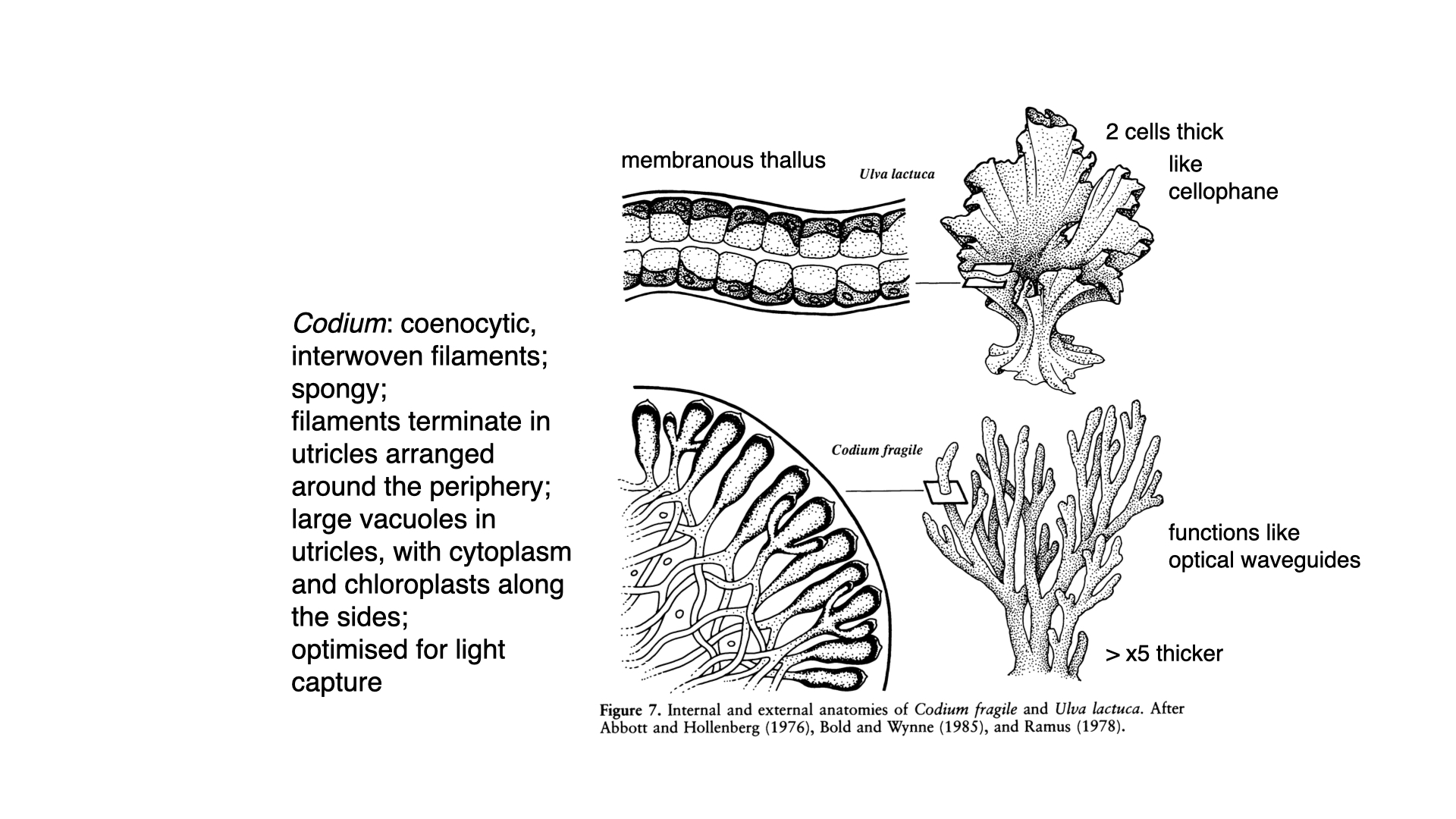

You will notice these represent two functional forms: the coarsely branched type (Chondrus and Codium) and the membranous group (Porphyra and Ulva). By spanning both different pigment groups and functional forms, Ramus and colleagues devised a transplant experiment to address how various algae types acclimatise to different oceanic light levels.

14.2 Comparing functional forms and light adaptation

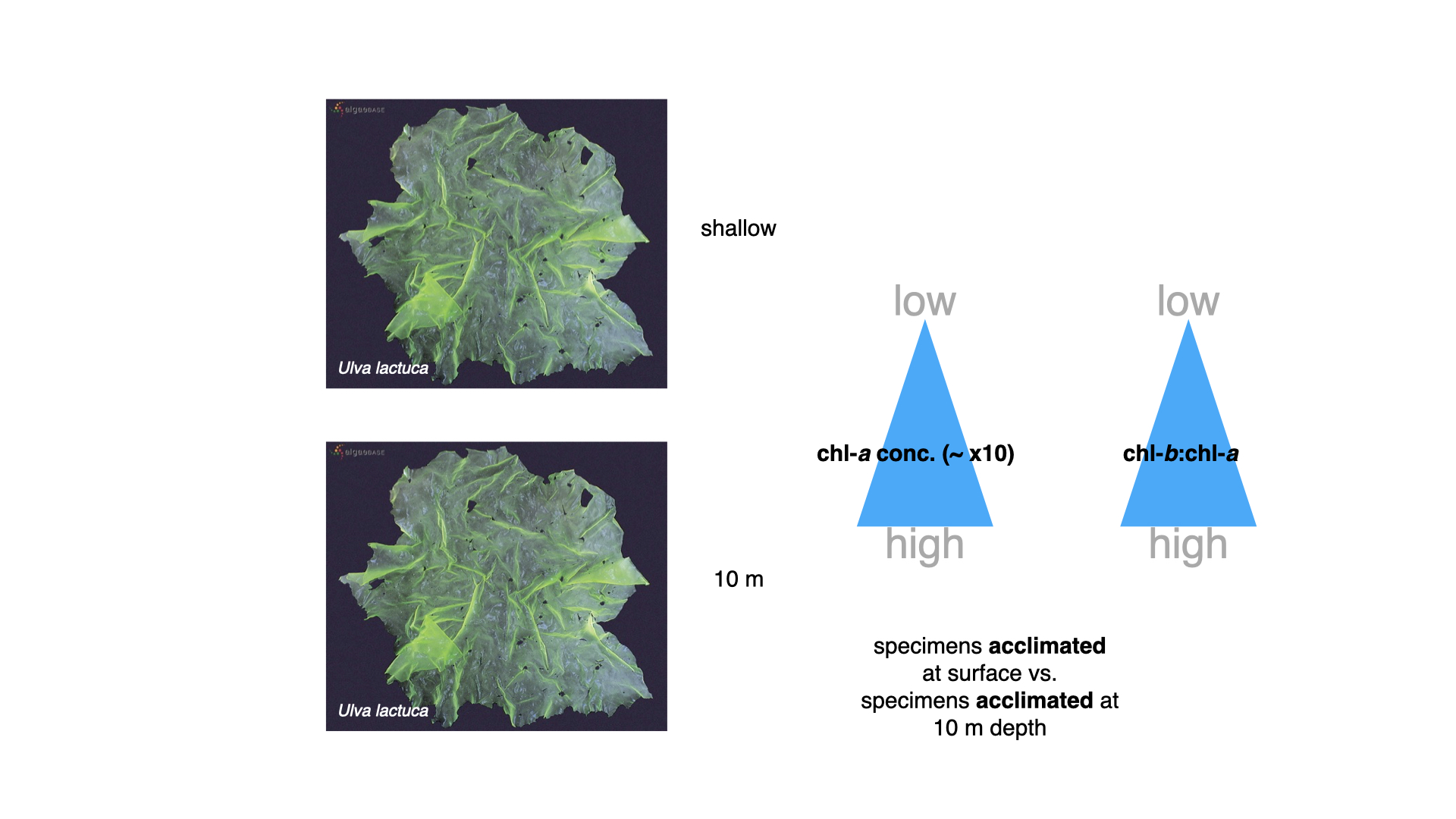

So, focusing on comparisons within the same functional form, particularly the membranous group—Ulva and Porphyra, green and red respectively — let us consider specimens acclimatised to

However, when expressing photosynthetic rate per gram of tissue (i.e., per gram of Ulva or Porphyra), Ulva outperforms Porphyra. The underlying reason is simple: one gram of Ulva contains more chlorophyll-a than one gram of Porphyra. This makes sense, since Ulva is mainly composed of chlorophyll-a, whereas in Porphyra, much of the pigment content consists of accessory pigments (principally phycobilins), rather than chlorophyll-a.

14.3 Surface area to volume effects

Additionally, when comparing red and green seaweeds at

14.4 Transplant experiments: shallow vs deep

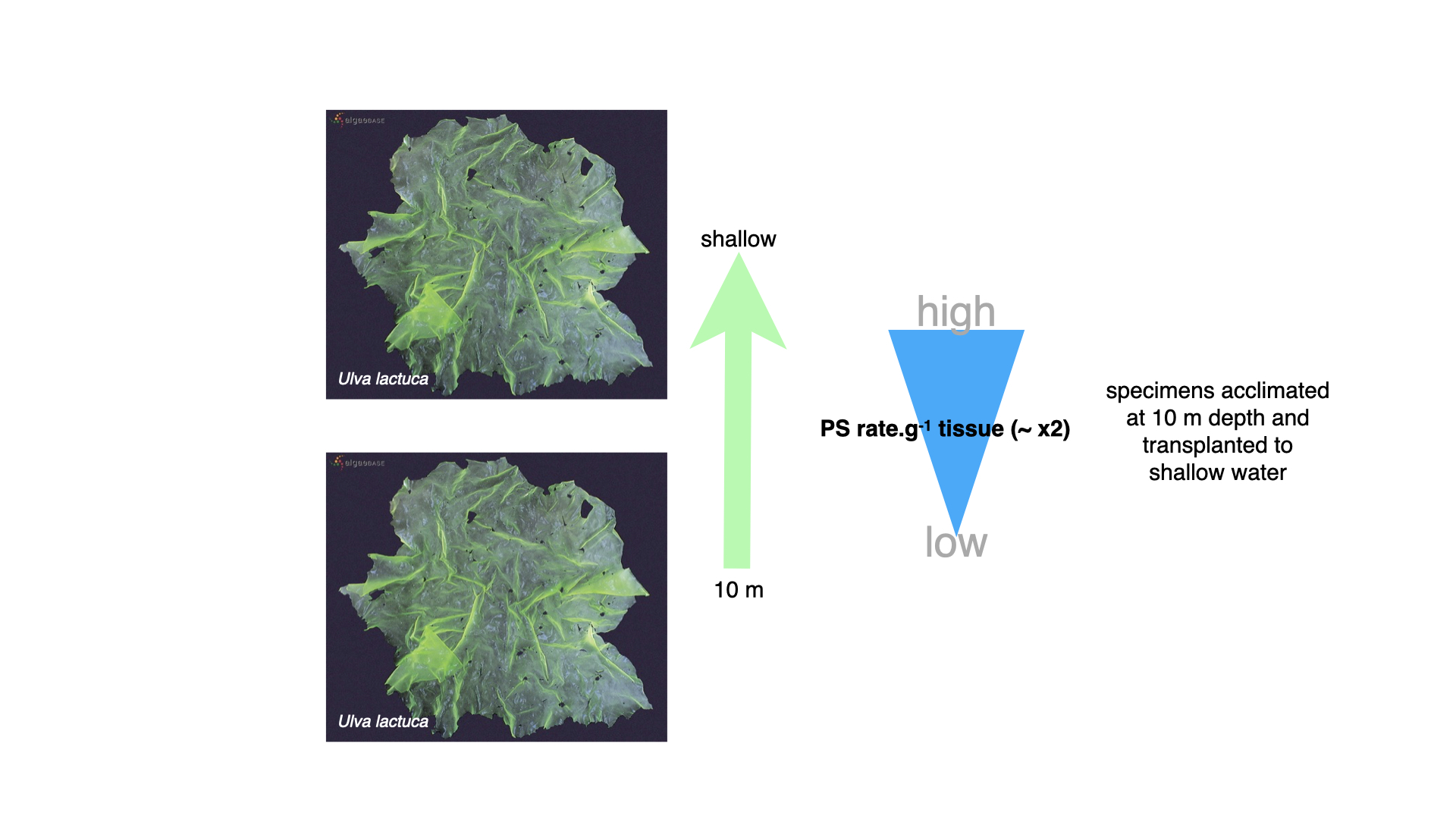

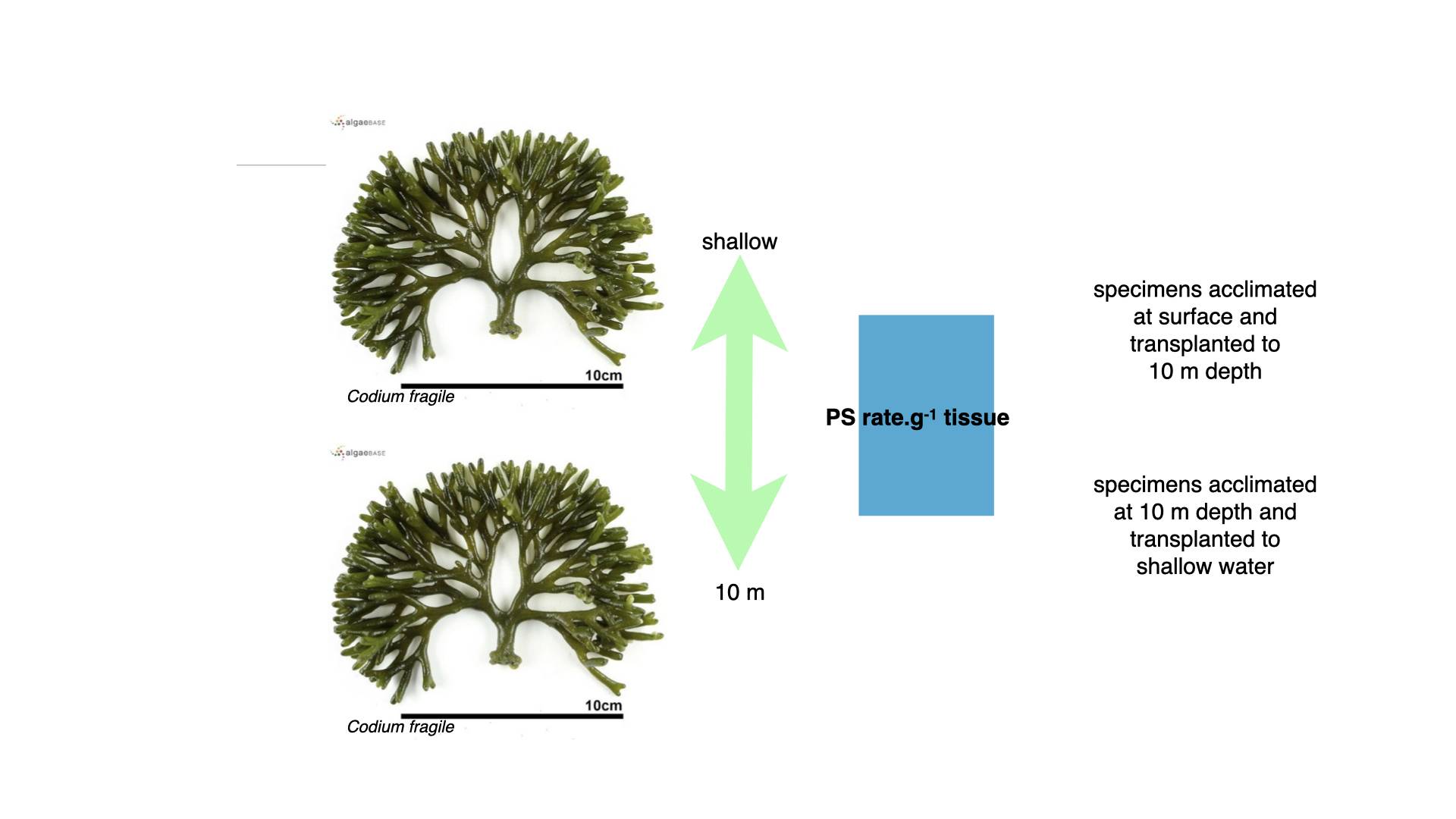

For the transplant experiments, they took seaweeds acclimatised to

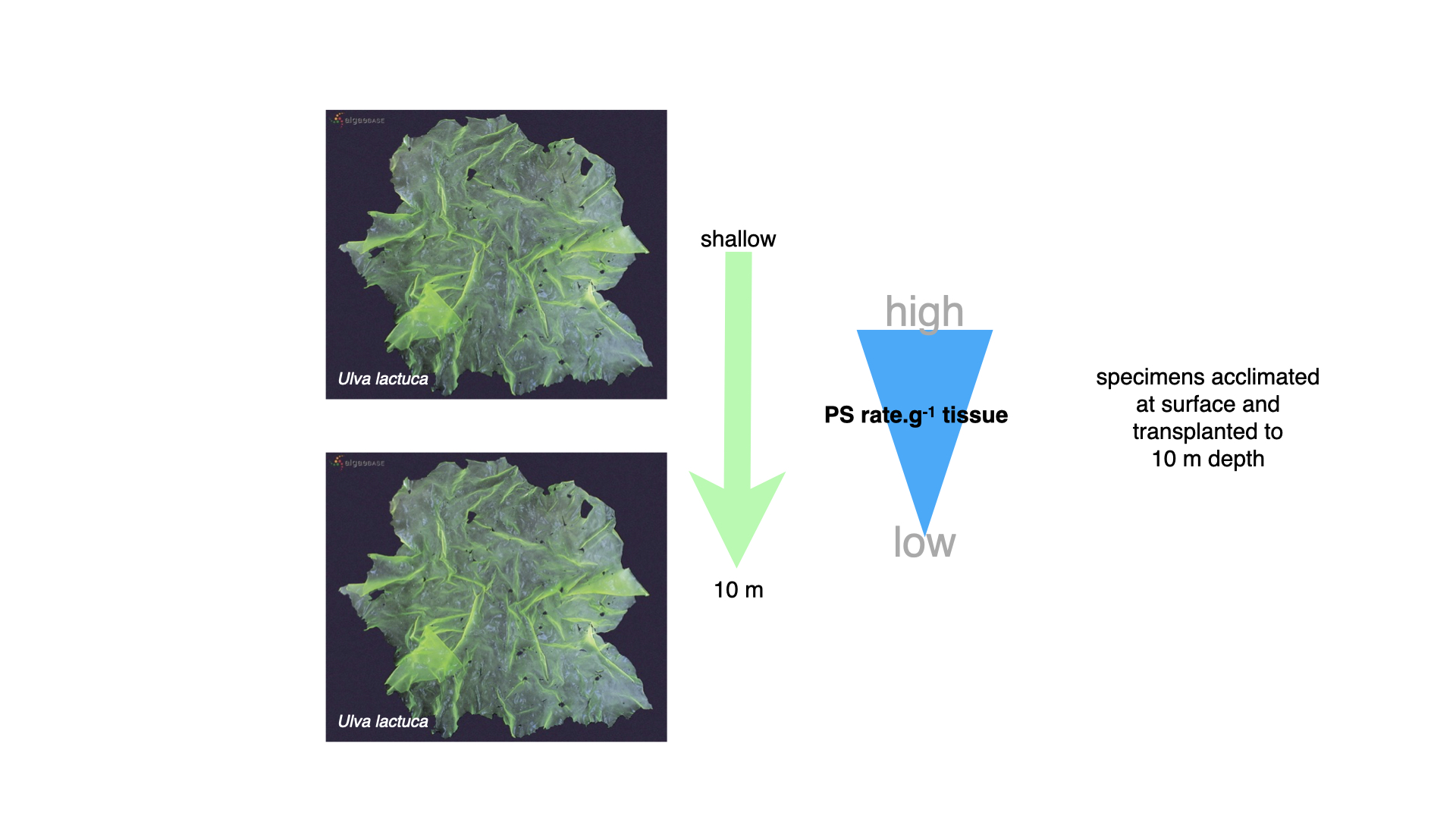

Executing the reverse — transplanting from the surface to

Comparing pigment concentrations, seaweeds acclimatised to

Codium, the coarsely branched green alga, however, presented a different case. Regardless of being grown shallow or deep, the rate of photosynthesis per gram of tissue remained nearly identical, even after transplantation.

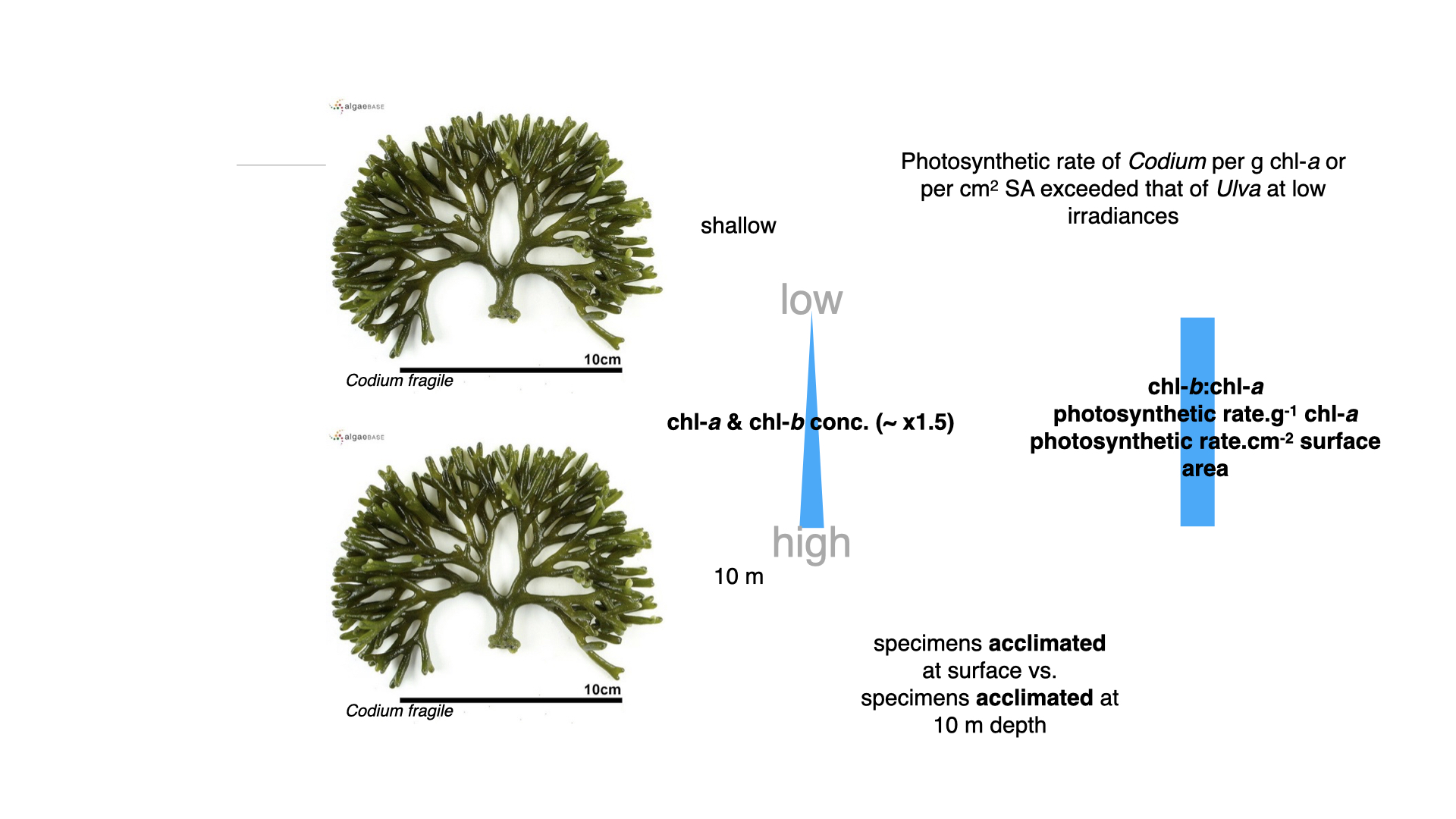

Looking into pigment concentrations for surface versus deep-acclimatised Codium, the difference was marginal — only about 1.5 times higher chlorophyll-a and b at depth. Moreover, neither the ratio of chlorophyll-b to chlorophyll-a, nor photosynthetic rates per chlorophyll-a or per surface area, differed much between environments.

In summarising all these results, many types of comparisons arise, helping test numerous hypotheses concerning seaweed acclimatisation and adaptation to varying environments.

14.5 Acclimatisation mechanisms and plasticity

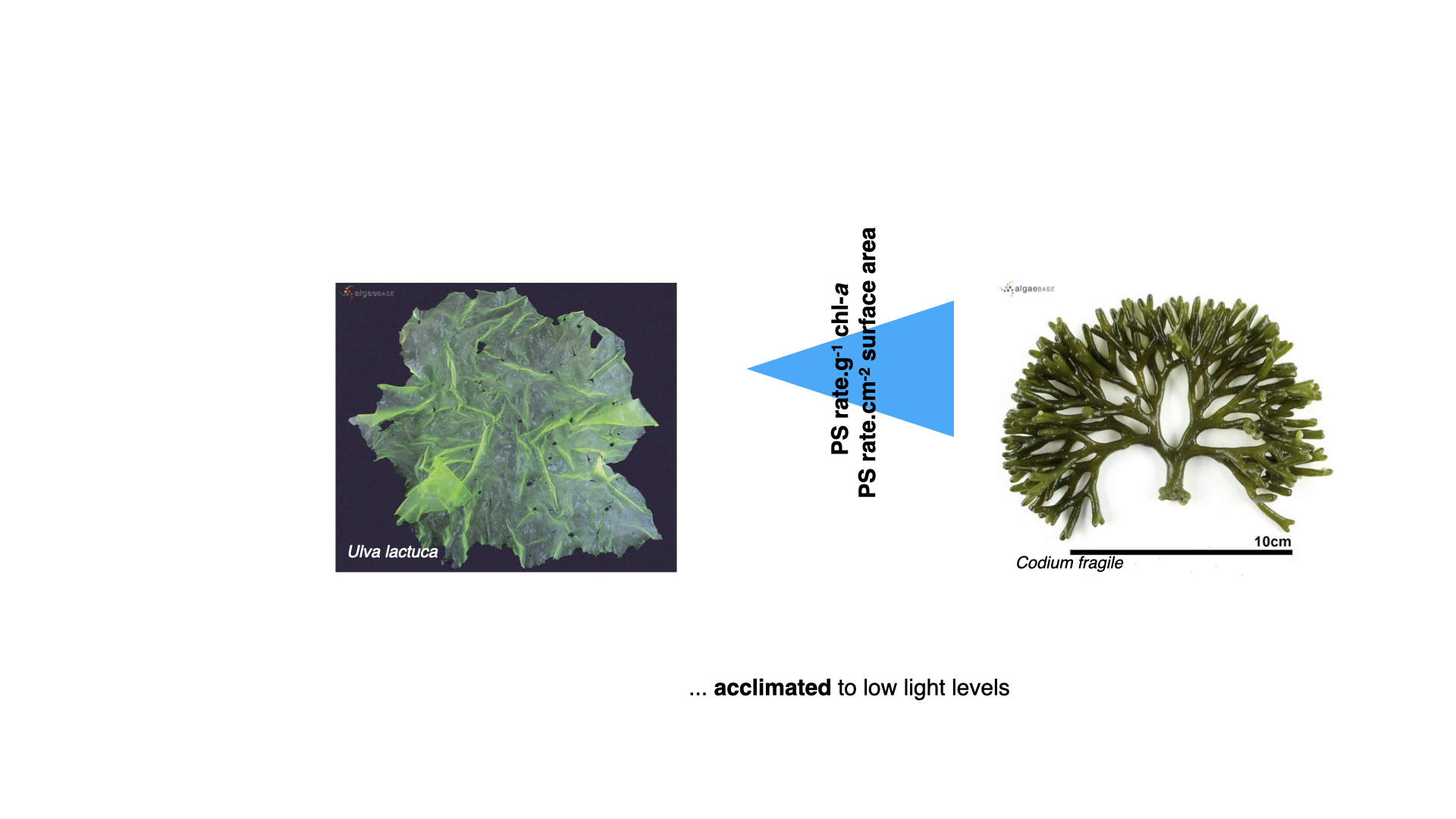

Once seaweeds were acclimatised to low light, they found that the photosynthetic rate per gram of chlorophyll-a in Codium—the coarsely branched green alga — was higher, and likewise, rate per unit surface area was greater compared with Ulva.

So, what is happening? This mountain of data reveals several important adaptive responses. For seaweeds like Ulva, this can be understood via the plasticity of their photophysiological mechanisms. Ulva, for instance, can modify its physiology, pigment composition, and growth responses in reaction to prevailing environmental conditions — a demonstration of physiological plasticity.

So, as Ulva is transplanted from high to low light (surface to depth), an immediate reduction in photosynthetic rate occurs — less light equals less photosynthesis. This represents the organism being placed at a lower segment of its PI (photosynthesis–irradiance) curve. However, left at depth for several weeks, Ulva gradually manufactures more chlorophyll-a and invests more energy into accessory pigment production (chlorophyll-b). The increased chlorophyll content raises light-harvesting capability, bringing the photosynthetic rate back up — sometimes reaching up to ten times greater than for non-acclimatised specimens moved directly from the surface to depth.

The ratio of chlorophyll-b to a rises too, signifying compensatory synthesis of accessory pigments under dim conditions.

The opposite holds when moving from deep to shallow: photosynthesis rates spike instantly, but over time, pigment concentrations (particularly chlorophyll-b relative to chlorophyll-a) decrease, as high irradiance makes accessory pigments unnecessary. But across all conditions, the photosynthetic rate per gram of chlorophyll-a remains constant, because chlorophyll-a’s physiological efficiency as a light-harvesting molecule does not change with acclimatisation.

14.6 Codium’s distinctive behaviour

Codium, however, does not behave the same way. Despite having similar pigments to Ulva, its internal architecture is markedly different, which underpins its dissimilar responses.

14.7 Structural and optical differences: ulva vs codium

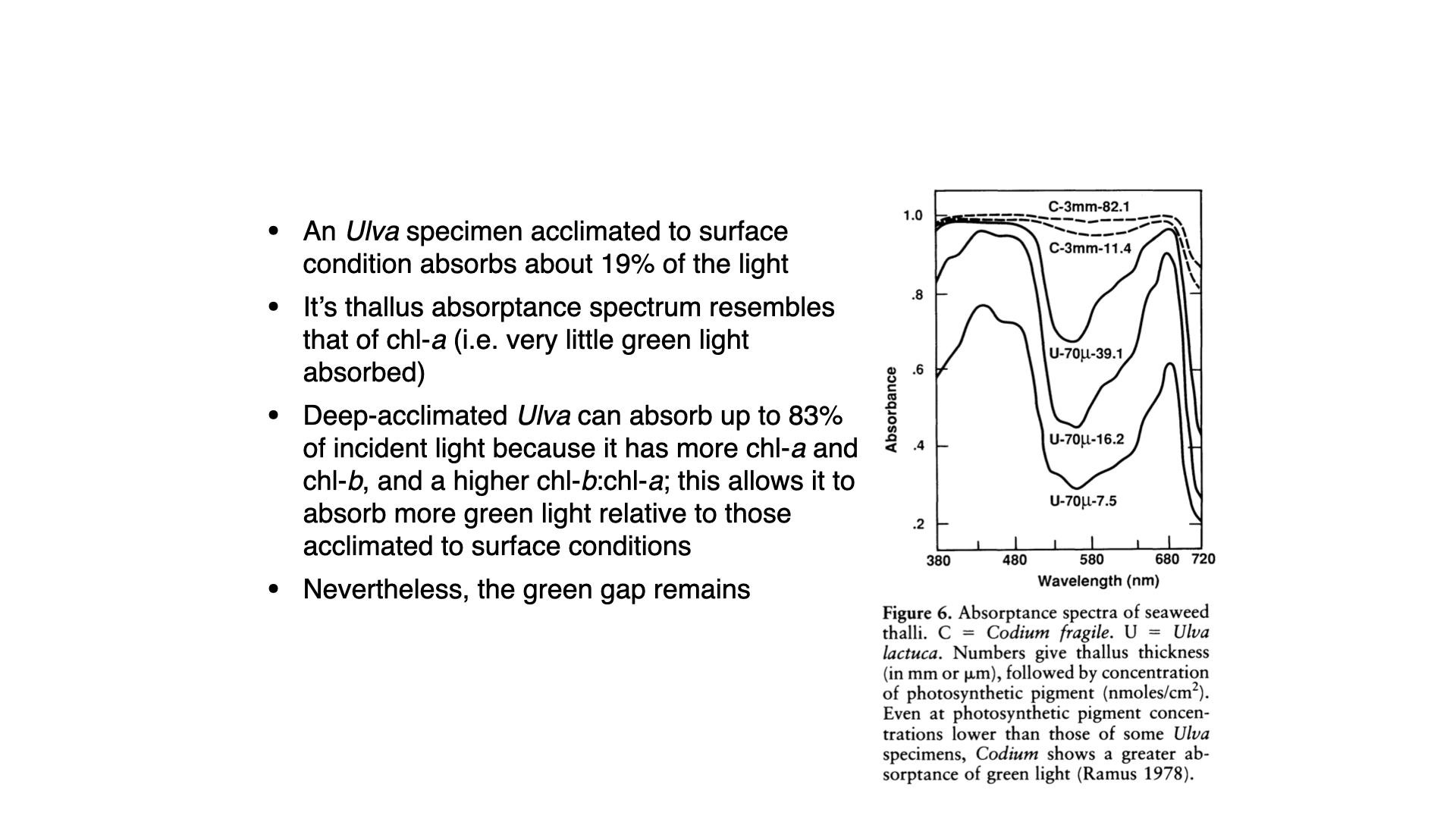

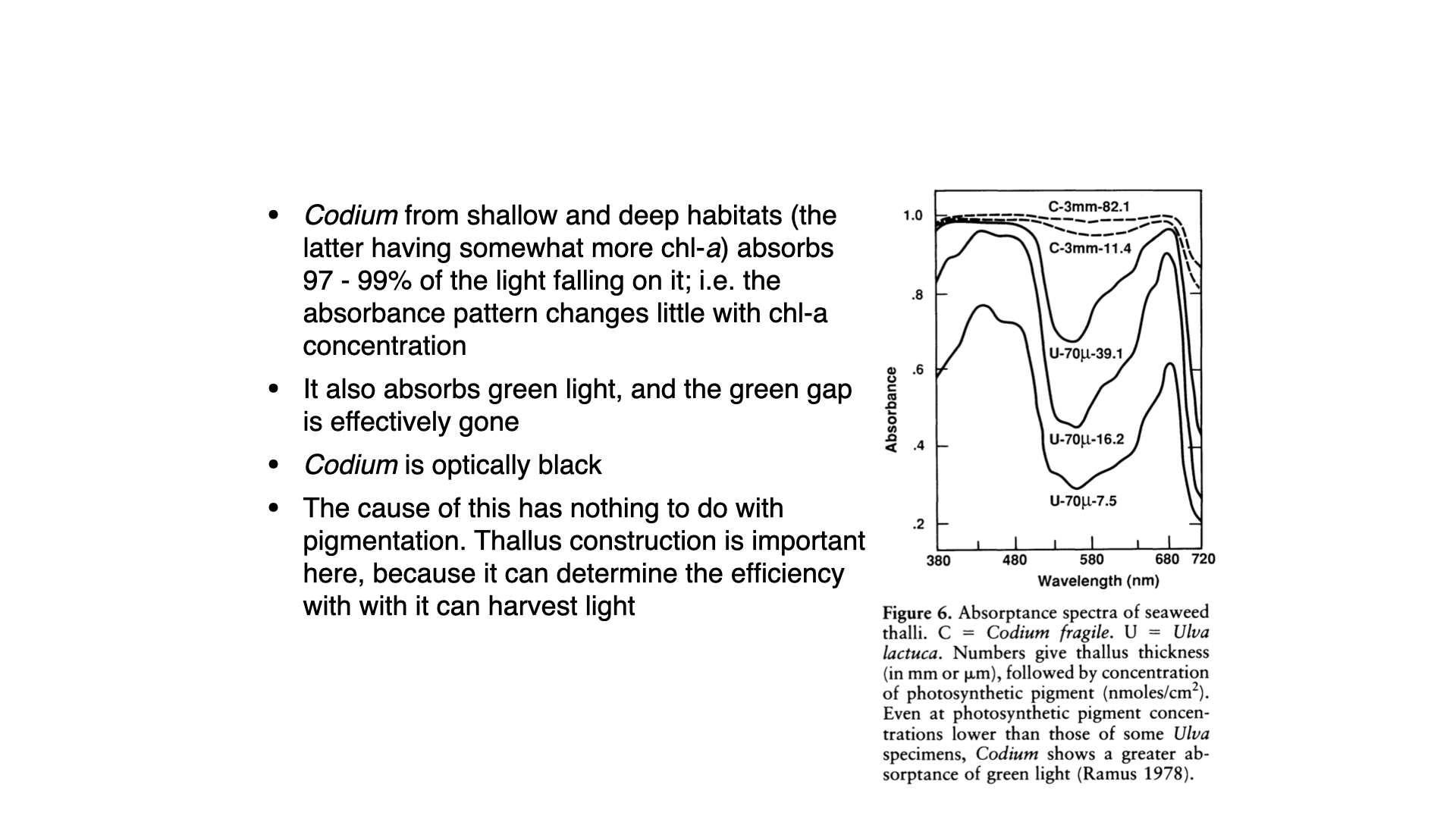

To clarify, let us examine Ulva. Surface-acclimatised Ulva absorbs only

At high light, absorption is reduced — the organism is inefficient at harvesting all incident light, since what it does capture is ample for its needs. Its high surface area to volume ratio allows rapid translation of harvested light into growth.

Transplanted to depth, the same thin Ulva thallus ramps up its pigment content — notably chlorophyll-a—and thus absorbs more light across the spectrum, especially when blue and red light dominate at depth. Absorption in the green region (the “green gap”), as well as across the spectrum, increases because accessory pigments like chlorophyll-b accumulate.

But even with increased pigment content, there is always a green gap, as Ulva lacks the accessory pigments required to efficiently absorb green wavelengths. Interestingly, Codium also lacks such accessory pigments, yet it is able to absorb significant amounts of light even in the green gap.

The reason is that Codium is optically black. That is, its tissues are so densely packed with pigment, particularly chlorophyll-a, within a very thick (

In an optically black seaweed, chlorophyll-a molecules retain their intrinsic absorption spectrum: they are “green” pigments, so they reflect and transmitting green light near 550 nm. How, then, can an alga, composed substantially of these same pigments, appear optically black and absorb almost the entirety of the incident spectrum (including the green light that individual chlorophyll-a pigments reflect)? The answer lies in the convergence of several mechanisms, i.e., complementary pigment absorption profiles, structural light scattering, and path length enhancement within the thallus architecture. These factors interact to suppress reflectance and transmittance across the visible range to produce near-total absorptance despite the spectral limitations of chlorophyll-a alone.

The first and most direct contributor is accessory pigment composition. While chlorophyll-a dominates absorption in the red and blue regions of the spectrum, its absorption coefficient near 550 nm drops to roughly 10–15% of peak values. This is a substantial reduction but it never reaches absolute zero. In Codium, as in other chlorophytes, chlorophyll-b and carotenoids provide spectral coverage beyond chlorophyll-a’s reach. Siphonaxanthin and siphonein, the predominant carotenoids in Codium, absorb in the blue-green portion of the spectrum (approximately 450–550 nm), and this partially fills the chlorophyll-a “green gap.” The cumulative absorption spectrum of the pigment complement therefore exhibits greater breadth than chlorophyll-a in isolation, and reduces the transmission window that would otherwise produce a green appearance. The degree to which carotenoids alone account for the dark phenotype depends on their concentration relative to chlorophyll-a (which varies with species, light environment, and physiological state) but their contribution cannot be dismissed. In many visibly dark algae, accessory pigments provide the primary mechanism for broadband absorption; red algae and cyanobacteria, for instance, rely on phycobilins that absorb intensely in the green, causing them to appear brown, red, or nearly black depending on pigment ratios.

Pigment chemistry alone does not fully explain the optical behaviour of structurally complex tissues. Even with residual chlorophyll-a absorption and supplementary chlorophyll-b and carotenoids, a sparse distribution of pigments in an optically thin medium would still permit significant reflectance and transmittance of green wavelengths. What transforms this accessory pigment cocktail into a near-perfect absorber is the optical organisation of the thallus, i.e., the three-dimensional arrangement of pigments within a scattering matrix that dramatically alters the internal light field.

When photons enter a densely pigmented, structurally heterogeneous tissue such as Codium, they encounter multiple refractive index discontinuities: cell walls, cytoplasm-vacuole interfaces, chloroplast membranes, and potentially air-water boundaries in the tubular, siphonous thallus structure characteristic of the genus. Rather than crossing the tissue in a direct path, photons undergo repeated scattering events which redirect their trajectories through the pigment-dense cytoplasm. This process extends the effective optical path length far beyond the physical thickness of the tissue. Wavelengths that would be poorly absorbed in a single encounter with chlorophyll-a (green photons, for instance) are subjected to tens or hundreds of absorption opportunities as they ping-pong through the scattering medium. Over many scattering events, the cumulative probability of absorption approaches unity even for wavelengths with modest absorption coefficients, provided those coefficients are non-zero.

This effect is captured by the concept of optical thickness, a dimensionless parameter relating the physical depth of a medium to the mean free path of photons within it. A medium is optically thin when photons typically escape before absorption; it is optically thick when the probability of absorption during the photon’s residence time approaches one. In an optically thick tissue with high pigment loading, the reflectance spectrum flattens, and overall absorptance across the visible range rises toward unity. Codium achieves optical thickness through both its inflated, tubular morphology (which maximises tissue volume and internal scattering interfaces) and its high pigment concentration, producing behaviour resembling that of an optically black medium under natural illumination. (The term “black body” is sometimes invoked colloquially but is imprecise, as it conflates absorptive properties with thermal emission characteristics irrelevant to photosynthetic optics.)

The interaction between pigment concentration and scattering introduces something else. Increasing pigment density enhances absorption per unit path length but may simultaneously alter scattering properties depending on how pigments are spatially distributed. Dense chloroplast packing or thylakoid stacking can reduce the number of refractive index discontinuities available to scatter light, potentially decreasing scattering efficiency even as absorption increases. Conversely, pigment aggregates or densely stained organelles can themselves introduce scattering centers if their refractive index differs sufficiently from the surrounding cytoplasm. The net optical effect … whether a tissue behaves as a strong scatterer, a strong absorber, or both … depends on the microstructure of the thallus, the subcellular pigment placement, and the balance between absorption and scattering cross-sections. These parameters are not easily generalised across taxa or even across different tissues within a single organism, and quantitative assessment requires spectrophotometric measurements that partition absorption from scattering, often using integrating sphere techniques or inverse Monte Carlo modelling of light transport.

So, the green gap in chlorophyll-a absorption is not chemically eliminated in Codium or any other dark alga; chlorophyll-a retains its characteristic minimum near 550 nm. Rather, the structural context removes escape routes for green photons through scattering-mediated path length enhancement, while accessory pigments provide direct absorption in spectral regions where chlorophyll-a is weakest. The relative contributions of these two mechanisms (pigment complementarity versus structural optics) is an empirical question dependent on the specific organism and its physiological state. In Codium, the high chlorophyll-b and carotenoid content suggests that pigment chemistry plays a non-negligible role, but the siphonous, tubular morphology and dense pigment packing almost certainly amplify absorptance through scattering effects as well.

The broader implication is that tissue-level optical properties cannot be predicted from pigment absorption spectra alone, nor from morphology in isolation. The interaction between chemistry and structure determines photon fate, and organisms tuned by natural selection to maximise photon capture exploit both dimensions. The dark appearance of Codium reflects this integration: pigments absorb wavelengths directly where their coefficients are large, and structural scattering compensates for regions where molecular absorption is weak but non-zero. The pigment remains green in the sense that isolated chlorophyll-a molecules would still reflect green light if examined in dilute solution; the alga behaves as an optically black absorber because its three-dimensional organisation ensures that green photons, once admitted to the tissue, are unlikely to re-emerge.

The concentration of chlorophyll-a at the periphery means that any incident light is almost certainly absorbed before it can penetrate far, or it becomes trapped and wave-guided by the internal filaments, ensuring maximal light capture. This is why Codium maintains consistently high photosynthetic efficiency and pigment concentrations independent of depth, and thus shows little acclimatory response.

Ulva, by contrast, with its thin, “cellophane” membrane, allows much light to pass through, relying on every cell receiving direct illumination, but cannot match Codium’s absorptive efficiency in the green region or at depth.

15 Conclusion

So, to summarise: Ulva demonstrates remarkable plasticity in pigment and physiological responses, allowing acclimatisation to new light regimes — and does so primarily by increasing pigment concentrations at depth. Codium, by virtue of its dense, optically black construction and peripheral pigment placement, absorbs much more light and shows less need for physiological adjustment. Light absorption and photosynthetic rate per chlorophyll-a remain steady, but overall structural and anatomical properties, plus pigment arrangement, explain differences in adaptive responses between these two types of green algae.

That covers the key findings and interpretations you need to understand regarding light capture strategies and chromatic adaptation in seaweeds.

Reuse

Citation

@online{smit,_a._j.,

author = {Smit, A. J.,},

title = {Lecture 7: {Chromatic} {Adaptation}},

url = {http://tangledbank.netlify.app/BDC223/L07-chromatic_adaptation.html},

langid = {en}

}