Class tests

Questions and Answers

Question 1

Discuss the unimodal species distribution model, and describe how this model can explain the structuring of communities along environmental gradients. In your discussion, also talk about β-diversity.

Answer

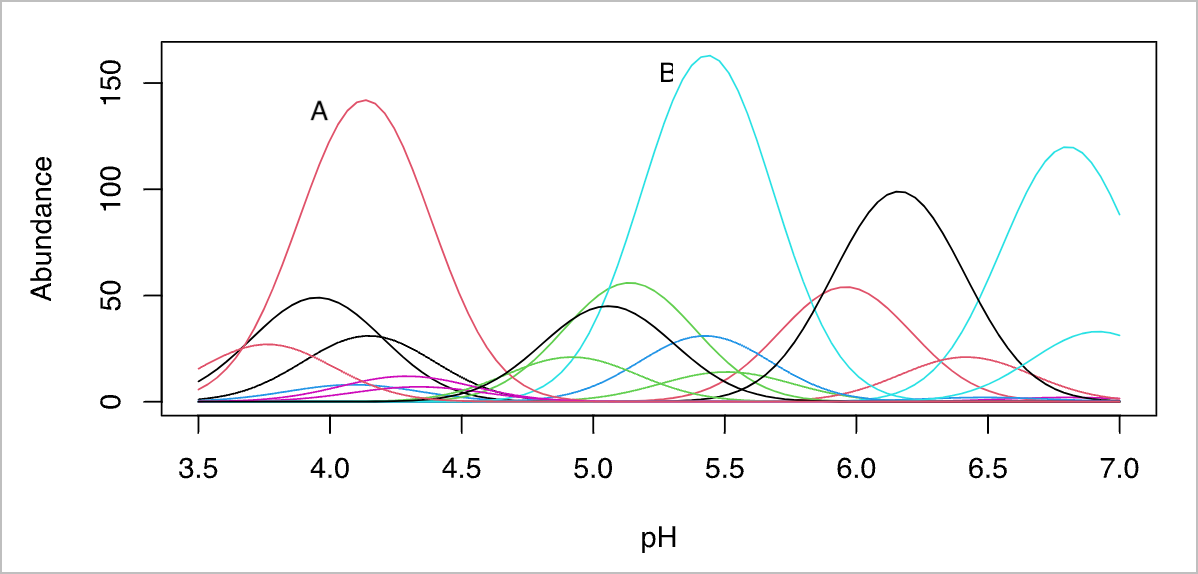

The unimodal model is an idealised species response curve where a species has only one mode of abundance—i.e. one locality on the landscape where conditions are optimal and it is most abundant (i.e. the fewest ecophysiological and ecological stressors are present there). If any aspect of the environment is suboptimal (greater or lesser than the optimum), the species will perform more poorly and have a lower abundance (a lower fitness). The unimodal model in the most basic sense can be seen as a Gaussian curve, and it offers a convenient heuristic tool for understanding how species can become structured along environmental gradients. Multiple unimodal distributions are often visualised as a coenocline—a graphical display of all species response curves, which shows how a species’ fitness is affected by any one of a multitude of environmental variables e.g. pH in Figure 1.

\(\beta\)-diversity is a concept that describes how species assemblages (communities) measured within the ecosystem of interest vary from place to place, e.g. along the various transects or among the quadrats used to sample the ecosystem. \(\beta\)-diversity can result from the gradual change in environmental characteristics along gradients. This can be clearly seen in a coenocline, where the modal centre of distribution of many species is arranged at different positions along an environmental gradient. See Figure 1. As Species A becomes less abundant when its physical distance away from the place on the landscape which is most conducive to its fitness increases, so it is replaced by Species B at a distant location where its environmental conditions are optimal. And so on with all the other species along the length of the gradient. This process is called environmental filtering, which results in a decrease in similarity as the distance between sites increases—sometimes this is called the niche difference model. Such patterns are typically visible along steep environmental gradients such as elevation slopes (mountains), latitude, or depth in the ocean, to name only three. It is also the dominant mechanism underlying island biogeography.

Question 2

Using a clear example that you can easily relate to, discuss the concept of ‘ecological infrastructure.’ In your explanation, mention other (i.e., in addition to the ‘infrastructural services’) ecological services this example ecosystem offers and any other benefits that people might derive from its existence and well-being. In your discussion, explain how the ecological infrastructure works (what it does and how) in a properly functioning ecosystem and, if people destroyed it, how we might replicate its service.

Answer

Wetlands as ecological infrastructure

What is ecological infrastructure? Ecological infrastructure is natural ecosystems that provide services beneficial to people. These services would, in the absence of ecological infrastructure, have to be provided by engineering solutions.

Benefits people derive from wetlands People tend to develop settlements, towns and cities in low-lying areas such as flood plains around estuaries. These areas are prone to periodic rising water levels, and recently they are also more and more being impacted by extreme floods (associated with climate change). Healthy flood plains often comprise wetlands, which are habitats occupied by dense emergent macrophytes along the edges of estuaries and flood plains. These systems can provide a buffer to rising water levels, and they may reduce the flow rate of water. People can benefit from intact wetlands as this buffer zone provides a level of protection to built structures in the vicinity of the estuaries. Wetlands also purify the water (water filtration removes excessive N, P and POM), which makes for an environment that is more supportive of good human health (fewer water borne diseases and pollutants which may be a public health concern).

However, often wetlands are destroyed by dredging and then filled in to make area available for occupation by people. In such transformed systems, protection against floods and rising water levels can be provided by constructing engineered systems at great cost. Examples of such engineered systems include breakwaters and levees. These systems, however, do not provide the other services required for maintaining good water quality, and additional engineering solutions, costing yet more tax-payers money, need to be provided. Additionally, downstream natural areas on which people depend will also become increasingly impacted due to the deterioration or loss of wetlands, and engineering solutions cannot mitigate against such consequences.

Thus, ecological infrastructure provide services to people simply by virtue of being maintained in a healthy state. This economic cost of achieving this is virtually non-existent, provided people act responsibly to protect these systems.

Ecological services from wetlands Wetlands provide a complex 3D habitat that provides numerous ecological services to a host of associated fauna and flora. These biotic assemblages benefit from their association with wetlands from the feeding/foraging opportunities provided within the habitat structure, the breeding and nursery grounds wetlands provide, attachment surfaces on the wetland plants and the sediments trapped within, and shelter and hiding opportunities from predators. Wetlands also reduce the flow rate of the water passing through them, and as such the still water within is attractive to some species that are unable to tolerate faster flow rates. Typically, healthy wetlands are active in their cycling (uptake) of N and P, and as such the water quality may be better compared to surrounding areas. This is also true for decreasing the water turbidity due to their filtration services. This makes wetlands ideal environments to some species that are sensitive to pollution. <Many more services are provided by the sediments in wetlands, which offer additional opportunities for enhancing biodiversity in these areas>. Overall, the net effect it that it supports species diversity, i.e. higher biodiversity in landscapes with functional wetlands present compared to areas without wetlands. Higher species diversity also offer many bequest services, and offer a potential source of genetic diversity and materials to assay for important bio-active substances that might be useful to people.

Question 3

Discuss the general characteristics of species tables, environment tables, and dissimilarity and distance matrices we can derive from these tables.

Answer

Environmental tables Environmental tables have variables down the columns (headings are the names of the env vars) and the sites run across the columns (row names are the names of the sites), with one site in a row. Different kinds of environmental variables can be contained in the table, as many as the researcher thinks is necessary to explain the patterns in the species tables. In the cells are the quantities of the various environmental variables measured at the different sites. The measurement units may differ between columns, so later, before analysis, these data must be standardised.

Species tables The species tables have as many rows as the number of rows in the environmental table—so, for each site where species are recorded, there will be corresponding measurements of the environmental conditions there. Rows in a species table have the same orientation and meaning as in the environmental table. The columns, however, contain the names of the species recorded at the sites. In the cells is some quantity that reflects something about the species at the sites—it might indicate whether a species is there or not (presence/absence), its relative abundance, or biomass. The way in which the species are quantified must be the same across all columns.

Dissimilarity matrix The dissimilarity matrix is derived from the species table by calculating one of the species dissimilarity indices (Bray-Curtis, Sørensen, Jaccard, etc.). It is square and symmetrical, and the diagonals are zero because they are essentially comparing sites with themselves in respect to the kinds of species and their abundance or presence/absence there. A value of 1 would mean that the sites are completely different from each other—this would be seen in a similarity matrix, which is the inverse of a dissimilarity matrix. Each of the other cells represent the community difference between a pair of sites whose names are present as column or row headers.

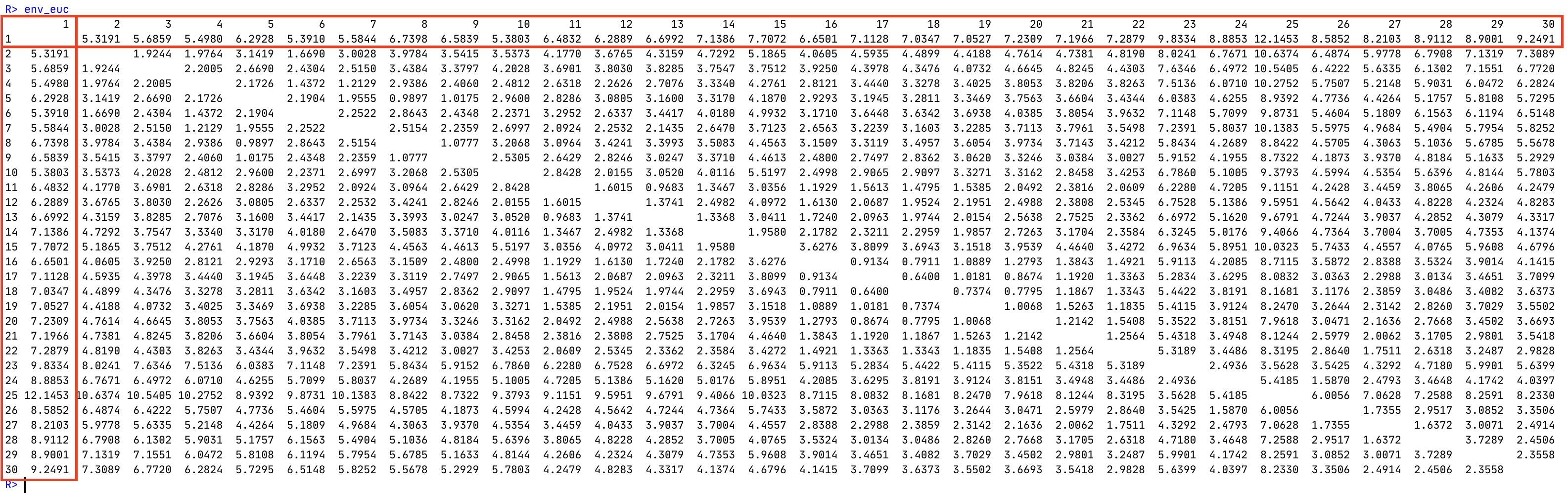

Distance matrix A distance matrix is produced from a standardised environmental table. It is square and symmetrical, and there are as many rows and columns as there are variables in the environmental table. This matrix reflects how similar/dissimilar pairs of sites are with regards to the environmental conditions present there. The interpretation of the diagonal is the same as in dissimilarity matrices.

Question 4

Provide a short explanation, with examples, for what is meant by this statement:

“Communities often seem to display very strong structural graduation relative to ‘variables’ such as altitude, latitude, and depth; however, these variables are not the actual drivers of the processes that structure communities.”

Answer

Altitude, latitude, and depth serve to indicate the position sites on Earth’s surface. They do not have physical properties associated with them. Species cannot require altitude, latitude, or depth to sustain their physiological needs. They are merely proxy variables for other variables that can affect the physiology of the species occurring there. I am less interested in how beta-diversity (turnover, niche models, unimodal models) works, and more interested in how the proxy relationships might play out. For example, …

Question 5

It is the year 2034 and as a result of a decade of campaigning the South African Green Party has become a real contender to be the runner up behind the populist EFF, which has come into power in South Africa in 2029.

As the leader of the Green Party, write an Opinion Piece that outlines the ecological solutions your party has to offer for when (if) it becomes the official opposition to the current ruling party. Your party’s ecological solutions offer the promise of solving many of the socio-economic solutions that face South Africans in the 2030s.

Answer

This is an opinion piece and an expected answer is not available.

In this answer I am looking for how ecosystems’ ecological services and goods may be used for the betterment of people, the environment, and the economy. I am not looking for a listing of SA’s problems. I am not looking for way in which budgets can be better spent, or how enforcement can be improved. I am also not really looking for the implementation of renewable energy sources as wind or solar (although that will definitely be part of the solution). We know that hunger needs to be alleviated; people must be educated; we need better farming techniques; developments must be sustainable; and people’s economic freedom ensured. But how? How can we use nature’s solutions to do so?

We need to build into the various initiatives a reliance on the country’s natural infrastructure. We can also develop novel, fit-for-purpose ‘ecological’ infrastructure that incorporate many of the principles of natural ecosystems with the same kinds of benefits to people (e.g. roof-top gardens, integrated forming and aquaculture, etc.).

The essay must consider these kinds of things.

Question 6

Explain in a short (1/3 page paragraph) what is meant by ‘environmental distance.’

Answer

Environmental distance encompasses all the characteristics of a landscape, such as measurements of the variables temperature, water content, soil nutrient concentrations, pH, etc., in a manner that makes it possible to provide a single, integrative metric that informs the researcher how similar or different sites across the landscape are to each other. Environmental distances are typically calculated as Euclidian distances (using the Pythagorean Theorem), but others are available such as Gower’s or Manhattan Distances and can be used for specific needs. In R they can be calculated using the vegdist() function in the vegan package. The calculation results in a pairwise distance matrix, with each cell value containing the environmental distance between a pair of sites. All possible combinations of site pairs are represented in this square matrix. The larger the value between two sites—the distance—the more different sites are with respect to their environmental properties. These distances can be used as explanation for how species communities differ across the landscape, such that sites with large environmental distances between them typically develop very different ecological communities.

Question 7

Explain how the data in the site-by-species matrix can be transformed into species-area curves. What are species area curves, and what explains their characteristic shape? What is the purpose of these curves?

Answer

Taken mostly directly from the online resource.

Species accumulation curves (species area relationships, SAR) try and estimate the number of unseen species. These curves can be used to predict and compare changes in diversity over increasing spatial extent. Within an ecosystem type, one would expect that more and more species would be added (accumulates) as the number of sampled sites increases (i.e. extent increases). This continues to a point where no more new species are added as the number of sampled sites continues to increase (i.e. the curve plateaus). It plateaus because if a homogeneous landscape is comprehensively sampled, there will be a point beyond which no new species will be found as we sample even more sites.

Species accumulation curves, as the name suggests, works by adding (accumulation or collecting) more and more sites along \(x\) and counting the number of species along \(y\) each time a new site is added. In the community matrix (the sites × species table), we can do this by successively adding more rows to the curve (seen along the \(x\)-axis). In other words, we plot on \(y\) the number of species associated with 1 site (the site on \(x\)), then we plot the number of species associated with 2 sites (the sum of the number of species in Site 1 and Site 2), then the number of species in Sites 1, 2, and 3. Etc. We do this until the cumulative sum of the species in all sites has been plotted in this manner. Typically some randomisation procedure is involved (the order in which sites are added up is randomised).

Question 8

Using South African examples, discuss the principle of distance decay of similarity in biogeography and ecology.

Answer

To follow tomorrow (I’m tired now).

Question 9

Please refer to Figure 1:

- To graphically represent distance decay, we typically plot the data in the first column or first row (they are the same) of an environmental distance matrix. Why this row/column? What is unique about the first row/column? [3]

- How does the information in the first row/column differ from that in the subdiagonal? [3]

- What information is contained in any other cell in the environmental distance matrix? [2]

- What values are in the blanks down the diagonal? Why are these values what they are? [2]

Answer

Looking down the first column, the environmental distance tends to increase the further a site is from Site 1. This is because sites further away from the origin (Site 1) tend to become increasingly dissimilar in terms of their environmental conditions as a host of drivers impact on (e.g. in the Doubs data) the water quality variables—–e.g. near the terminus of the river several pollutants will have perturbed the system (flatter slopes are more conducive to polluting human developments). Typically the increasing environmental distance that develops further away from the origin can directly be attributed to a few very influential variables; again, in the Doubs data, it is the variables nitrate, ammonium, flow rate, and biological oxygen demand that primarily affect the trend in environmental distance. At the source, there are pristine conditions (low DIN and low BOD) and near the terminus sites are polluted. Similar explanations to this one can be developed for a host of environmental gradients (e.g. along the coastline of SA where there is a temperature gradient; across the country along the rainfall gradient; with altitude; with depth; etc.). Any of these can be used as examples.

Whereas the diagonal compares a site with itself, the subdiagonal (the diagonal row just one up or down from the diagonal filled with zeroes) captures the difference in environmental conditions (environmental distance) between adjoining sites (Site 1 vs Site 2, Site 2 vs Site 3, Site 3 vs Site 4, etc.). These changes are far more gradual than along the first row or down the first column. This is because the physical distance in geographical space is quite small for sites that are positioned next to one-another, and so too will be the environmental distance. Plotting these on a graph with environmental distance on \(y\) and the adjacent site pairs on \(x\) will generally yield a flat(-ish) line.

Any other cell simply compares any arbitrary site with any other in terms of the difference in environmental conditions between them. This environmental distance will also be (generally) quite closely related to the physical geographical distance (or altitude, depth, etc.) between the sites.

The ‘blanks’ are actually zeroes, which you would get if one would compare a site with itself. There is no difference between a site and itself, so hence no environmental difference between them.

Question 10

- Given a set of environmental data (e.g. pH, temperature, light, total N concentration, conductivity), what is the first step to follow prior to calculating environmental distance? Why is this necessary? [3]

- Provide an equation for how you would accomplish this first step. [2]

- What is the name of the equation / procedure to follow in the calculation of ‘environmental distance’? [1]

- Describe the principle of ‘environmental distance’. [9]

Answer

The first step would be to standardise the data. This is necessary because the different environmental variables are represented by different measurement scales (units). So, to prevent those with the largest magnitude (e.g. altitude, which is measured in 100s or 1000s of meters) to become the dominant ‘signal’ in the overall response when measured alongside something like temperature (10s of degrees Celsius), they have to be adjusted to comparables scales.

Standardisation involves calculating the mean of a variable, \(x\), and then subtracting this mean from each observation, \(x_{i}\). This value is then divided by the standard deviation of \(x\). So, something like \(x_{i} - \bar{x} / \sigma_x\).

Theorem of Pythagoras, or Euclidian distance.

Environmental distance encompasses all the characteristics of a landscape, such as measurements of the variables temperature, water content, soil nutrient concentrations, pH, etc., in a manner that makes it possible to provide a single, integrative metric that informs the researcher how similar or different sites across the landscape are to each other. Environmental distances are typically calculated as Euclidian distances (using the Pythagorean Theorem), but others are available such as Gower’s or Manhattan Distances and can be used for specific needs. In R they can be calculated using the

vegdist()function in the vegan package. The calculation results in a pairwise distance matrix, with each cell value containing the environmental distance between a pair of sites. All possible combinations of site pairs are represented in this square matrix. The larger the value between two sites—the distance—the more different sites are with respect to their environmental properties. These distances can be used as explanation for how species communities differ across the landscape, such that sites with large environmental distances between them typically develop very different ecological communities.

Question 11

What makes macroecology different from the traditional view of ecology?

Answer

Macroecology is an all-encompassing view of ecology, which seeks to define the geographical patterns and processes in biodiversity across all spatial scales, from local to global, across time scales from years to millennia, and across all taxonomic hierarchies (from genetic variability within species, up to major higher level taxa, such as families and orders). It attempts to arrive a unifying theory for ecology across all of these scales—e.g. one that can explain all patterns in structure and functioning from microbes to blue whales. Most importantly, perhaps, is that it attempts to offer mechanistic explanations for these patterns. At the heart of all explanation is also deep insights stemming from understanding evolution (facilitated by the growth of phylogenetic datasets—see below).

This is a modern development of ecology, whereas up to 20 years ago the focus has been mostly on populations (the dynamics of individuals of one species interacting amongst each other and with their environment) and communities (collections of multiple populations, and how they interact with each other and their environment, and how this affects the structure and dynamics of ecosystems).

On a basic data analytical level, population ecology, community ecology, and macroecology all share the same approach as far as the underlying data are concerned. We start with tables of species and environmental conditions (along columns) at a selection of sites (along rows), and these are converted to distance and dissimilarity matrices. From here analyses can show insights into how biodiversity is structured, e.g. species-abundance distributions, occupancy-abundancy curves, species-area curves, distance decay curves, and gradient analyses. In the last decade, modern developments in statistical approaches have contributed towards the development of macroecology, because of the growth of hypotheses-driven multivariate statistical approaches geared to test for the presence of one or several ecological hypotheses—this was not seen in population and community ecology so much. Contributing towards the growth of macroecology and the underlying statistical approaches, the deluge of new data across vast scales has also necessitated deeper analytical development, i.e. leveraging statistical tools and also the power of modern computing infrastructure. These modern approaches are also bringing into the fold of combined computations based on species and environmental tables also data on the phylogenetic relationships amongst organisms (and hence this brings the context of evolution).

Reuse

Citation

@online{j._smit2022,

author = {J. Smit, Albertus},

title = {Class Tests},

date = {2022-11-30},

url = {http://tangledbank.netlify.app/BDC334/Class_tests.html},

langid = {en}

}