Ordination

| Type | Name | Link |

|---|---|---|

| Slides | Ordination lecture slides | 💾 BCB743_07_ordination.pdf |

| Reading | Vegan–An Introduction to Ordination | 💾 Oksanen_intro-vegan.pdf |

The following methods are covered in the lecture slides. You are expected to be familiar with how to select the appropriate method, and how to execute each. Supplement your studying by accessing these sources: Numerical Ecology with R, GUSTA ME (see links immediately below), and Analysis of Community Ecology Data in R:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- Correspondence Analysis (CA)

- Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA)

- Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA)

- non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (nMDS)

- Redundancy Analysis (RDA)

- Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA)

- Distance-based Redundancy Analysis Analysis (CCA)

Ordination comes from the Latin word ordinatio, which means placing things in order (Chapter 9, Legendre and Legendre 2012). In ecology and some other sciences, it refers to a suite of multivariate statistical techniques used to analyse and visualise complex, high-dimensional data, such as ecological community data. In other words, high-dimensional data are ordered along some ‘reduced axes’ that explain patterns seen in nature. While clustering methods focus on identifying discontinuities or groups within the data, ordination aims to highlight and interpret gradients, which are ubiquitous in ecological communities.

Ordination is well-suited for handling multivariate ecological data, which can represent:

- A spatial context (e.g., a landscape) comprised of many sites (rows), each one characterised by multiple variables (columns), such as species abundances or environmental factors.

- A time series (e.g., repeated sampling) comprised of many samples (rows), each one containing multiple variables (columns), such as species or environmental variables.

- Multidimensional or multivariate data, where the number of dimensions (columns with information about species or environmental variables) approaches the number of samples (sites or times).

In such complex, high-dimensional data, analysing each variable separately using a series of univariate or bivariate analyses would be inefficient and unlikely to reveal the underlying patterns accurately. For example, in the Doubs River dataset, a univariate approach would require (27 × 26) / 2 = 351 separate analyses, which is impractical and prone to misinterpretation.

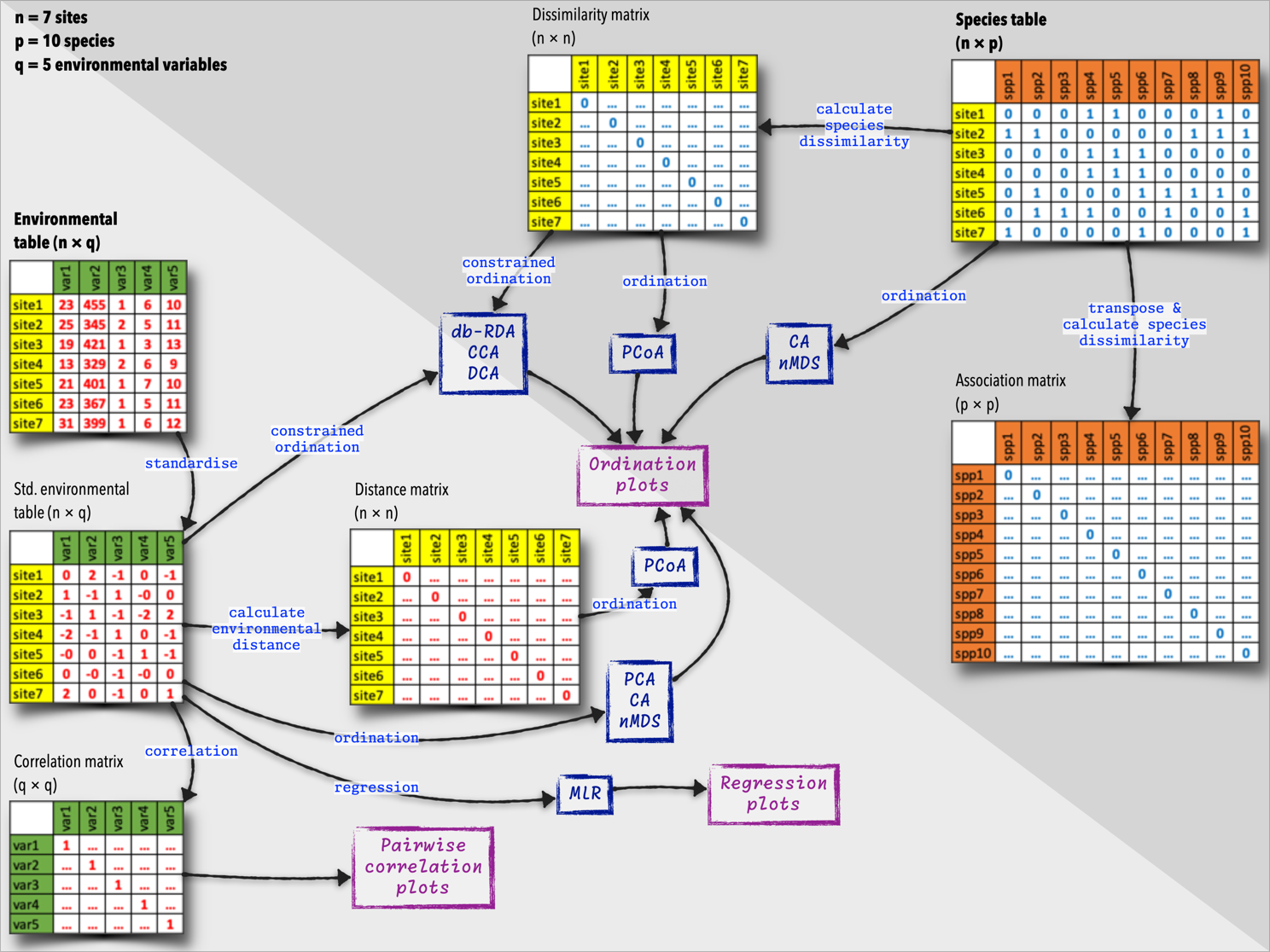

The multivariate data about environmental properties or species composition, which we present to the analyses as tables of species or environmental variables, can be prepared in different ways. The most common workflows involve the following steps (Figure 1):

- Species data: A table where each row represents a site or sample, and each column represents a species. The values in the table are species abundances, presences, or other species-related data.

- Environmental data: A table where each row represents a site or sample, and each column represents an environmental variable. The values in the table are environmental measurements, such as temperature, pH, or nutrient concentrations.

From here, we can derive the following types of matrices:

- Species × species association matrix: A matrix that quantifies the similarity or dissimilarity between species based on their co-occurrence patterns across sites.

- Site × site matrix of species dissimilarities: A matrix that quantifies the ecological differences between sites based on the species composition.

- Site × variable table of standardised environmental data: A table with standardised environmental conditions at each site.

- Site × site matrix of environmental distances: A matrix that quantifies the environmental differences between sites based on the environmental variables.

- Variable × variable correlation matrix: A matrix that quantifies the relationships between environmental variables.

Some of these newly-calculated matrices are then used as starting points for the ordination analyses.

Dimension Reduction

Ordination is a dimension reduction method. It:

- Takes high-dimensional data (many columns).

- Applies scaling and rotation.

- Reduces the complexity to a low-dimensional space (orthogonal axes).

Ordination represents the complex data along a reduced number of orthogonal axes (linearly independent and uncorrelated), constructed in such a way that they capture the main trends or gradients in the data in decreasing order of importance. Each orthogonal axis captures a portion of the variation attributed to the original variables (columns). Interpretation of these axes is aided by visualisations (biplots), regressions, and clustering techniques.

Essentially, ordination geometrically arranges (projects) sites or species into a simplified dataset, where distances between them in the Cartesian 2D or 3D space represent their ecological or species dissimilarities. In this simplified representation, the further apart the shapes representing sites or species are on the graph, the larger the ecological differences between them.

Imagine you have a 3D pear and a strong beam of light that casts the pear’s shadow onto a flat surface. When you place the pear in the beam of light, the shadow that forms on the surface represents a 2D projection of the 3D object. Depending on how you rotate the pear, the shadow can appear in different shapes. Sometimes, it looks like the characteristic pear shape, while other times, it might resemble a round disc or an elongated ellipse.

‘Projection’ in ordination works in a similar way. Consider the original data as the 3D pear, existing in a high-dimensional space where each dimension represents a different variable. The goal of ordination is to find new axes (principal components) that capture the most insightful variations in the data. These axes are akin to the rotation of the pear in the beam light to cast the shadow.

When you ‘project’ the data onto these new axes, you are essentially rotating the pear in the light beam to create a 2D (or lower-dimensional) shadow on a plane. This shadow, or projection, represents the data in a reduced form. Just like rotating the pear reveals different shapes of shadows, rotating the data (changing the axes) in ordination can reveal different structures and patterns within the data. Some rotations will clearly show the underlying structure (e.g., the pear shape), while others might obscure it (e.g., the round disc).

This process of projection helps in visualising complex, high-dimensional data in a simpler form and makes it easier to identify patterns, clusters, and relationships between variables.

The reduced axes are ordered by the amount of variation they capture, with the first axis capturing the most variation, the second axis capturing the second most, and so on. The axes are orthogonal, so they are uncorrelated. They are linear combinations of the original variables, making them interpretable.

“Ordination primarily endeavours to represent sample and species relationships as faithfully as possible in a low-dimensional space” (Gauch, 1982). This is necessary because visualising multiple dimensions (species or variables) simultaneously in community data is extremely challenging, if not impossible. Ordination compromises between the number of dimensions and the amount of information retained. Ecologists are frequently confronted by 10s, if not 100s, of variables, species, and samples. A single multivariate analysis also saves time compared to conducting separate univariate analyses for each species or variable. What we really want is for the dimensions of this ‘low-dimensional space’ to represent important and interpretable environmental gradients.

Benefits of Ordination

An ecological reason for preferring ordination over multiple univariate analyses is that species do not occur in isolation but in communities. Species in a community are interdependent and influenced by the same environmental factors. As such, community patterns may differ from population patterns. Some ordination methods can also offer insights into β diversity, which is the variation in species composition among sites.

A statistical reason for avoiding multiple univariate analyses is the increased probability of making a Type I error (rejecting a true null hypothesis) with numerous tests, known as the problem of multiple comparisons. In contrast, multivariate analysis has a single test, enhancing statistical power by considering species in aggregate due to redundancy in the data.

Ordination focuses on “important dimensions,” avoiding the interpretation of noise, thus acting as a “noise reduction technique” (Gauch, 1982). It allows determining the relative importance of different gradients, which is virtually impossible with univariate techniques. For example, one can assess whether the first axis represents a stronger gradient than the second axis.

A major benefit of ordination is that its numeric output lends itself to graphical representation, often leading to intuitive interpretations of species-environment relationships. This is useful for communicating results to non-specialists.

Types of Ordinations

The first group of ordination techniques includes eigen-analysis methods, which use linear algebra for dimensionality reduction. The second group includes non-eigen-analysis methods, which use iterative algorithms for dimensionality reduction. I will cover both classes in this lecture, with non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling being the only example of the second group.

The eigen-analysis methods produce outputs called eigenvectors and eigenvalues, which are then used to determine the most important patterns or gradients in the data. These properties and applications of eigenvectors and eigenvalues will be covered in subsequent sections. The non-eigen approach instead uses numerical optimisation to find the best representation of the data in a lower-dimensional space.

Below, I prefer a classification of the ordination methods into constrained and unconstrained methods. This classification is based on the type of information used to construct the ordination axes, and how they are used. Constrained methods use environmental data to construct the axes, while unconstrained methods do not. The main difference between these two classes is that constrained methods are hypothesis-driven, while unconstrained methods are exploratory.

Unconstrained Ordination (Indirect Gradient Analysis)

These are not statistical techniques (no inference testing); they are purely descriptive. Sometimes they are called indirect gradient analysis. These analyses are based on either the environment × sites matrix or the species × sites matrix, each analysed and interpreted in isolation. The main goal is to find the main gradients in the data. We apply indirect gradient analysis when the gradients are unknown a priori, and we do not have environmental data related to the species. Gradients or other influences that structure species in space are therefore inferred from the species composition data only. The communities thus reveal the presence (or absence) of gradients, but may not offer insight into the identity of the structuring gradients. The most common methods are:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): The main eigenvector-based method, working on raw, quantitative data. It preserves the Euclidean (linear) distances among sites, mainly used for environmental data but also applicable to species dissimilarities.

- Correspondence Analysis (CA): Works on data that must be frequencies or frequency-like, dimensionally homogeneous, and non-negative. It preserves the

- Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA): A variant of CA that is more suitable for species data tables with long environmental gradients which creates an interesting visual effect in the ordination diagram, called the arch-effect. Detrending linearises the species response to environmental gradients.

- Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA): Devoted to the ordination of dissimilarity or distance matrices, often in the Q mode instead of site-by-variables tables, offering great flexibility in the choice of association measures.

- non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (nMDS): A non-eigen-analysis method that works on dissimilarity or rank-order distance matrices to study the relationship between sites or species. nMDS represents objects along a predetermined number of axes while preserving the ordering relationships among them.

Constrained Ordination (Direct Gradient Analysis)

Constrained ordination adds a level of statistical testing and is also called direct gradient analysis or canonical ordination. It typically uses explanatory variables (in the environmental matrix) to explain the patterns seen in the species matrix. The main goal is to find the main gradients in the data and test the significance of these gradients. So, we use constrained ordination when important gradients are hypothesised. Likely evidence for the existence of gradients is measured and captured in a complementary environmental dataset that has the same spatial structure (rows) as the species dataset. Direct gradient analysis is performed using linear or non-linear regression methods that relate the ordination performed on the species to its matching environmental variables. The most common methods are:

- Redundancy Analysis (RDA): A constrained form of PCA, where ordination is constrained by environmental variables, used to study the relationship between species and environmental variables.

- Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA): A constrained form of CA, where ordination is constrained by environmental variables, used to study the relationship between species and environmental variables.

- Detrended Canonical Correspondence Analysis (DCCA): A constrained form of CA, used to study the relationship between species and environmental variables.

- Distance-Based Redundancy Analysis (db-RDA): A constrained form of PCoA, where ordination is constrained by environmental variables, used to study the relationship between species and environmental variables.

PCoA and nMDS can produce ordinations from any square dissimilarity or distance matrix, offering more flexibility than PCA and CA, which require site-by-species tables. PCoA and nMDS are also more robust to outliers and missing data than PCA and CA.

Ordination Diagrams

Ordination analyses are typically presented through graphical representations called ordination diagrams, which provide a simplified visual summary of the relationships between samples (the rows), species (columns), and environmental variables (also columns) in multivariate ecological data.

Basic Elements of Ordination Diagrams

- Sample Representation:

- Individual samples or plots (rows) are displayed as points or symbols.

- The relative positions of these points reflect the similarity (points plotting closer together) or dissimilarity (points spread further apart) between samples based on their species composition.

- Species Representation:

- In linear methods (e.g., PCA, RDA): Species are represented by arrows, with direction indicating increasing abundance and length suggesting rate of change.

- In weighted averaging methods (e.g., CA, CCA): Species are shown as points, representing their optimal position (often suggesting a unimodal distribution).

- Environmental Variable Representation:

- Quantitative Variables: Displayed as vectors, with the arrows’ direction showing the gradient of increasing values and length indicating correlation strength with ordination axes.

- Qualitative Variables: Represented by centroids (average positions) for each category.

- Default plot options use base graphics, but more advanced visualisations can be created using ggplot2.

Construction of the Ordination Space

- The coordinates given by the eigenvectors (species and site scores) are displayed on a 2D plane, typically using PC1 and PC2 (or PC1 and PC3, etc.) as axes.

- This creates a biplot, simultaneously plotting sites as points and environmental variables as vectors.

- The loadings (coefficients of original variables) define the reduced-space ‘landscape’ across which sites are scattered.

- Different scaling options (e.g., site scaling vs. species scaling) can emphasise different aspects of the data.

Interpretation of the Diagram

- Sample Relationships:

- Proximity between sample points indicates similarity in species composition.

- The spread of sites along environmental arrows represents their position along that gradient.

- Species-Environment Relationships:

- The angle between species arrows or their distance from sample points reflects association or abundance patterns.

- The arrangement of sites in the reduced ordination space represents their relative positions in the original multidimensional space.

- Environmental Gradients:

- Arrow length indicates the strength of the relationship between the variable and the principal component.

- The cosine of the angle between arrows represents the correlation between environmental variables.

- Parallel arrows suggest positive correlation, opposite arrows indicate negative correlation, and perpendicular arrows suggest uncorrelated variables.

- Biplots are heuristic tools and patterns should be further tested for statistical significance if necessary.

- Outliers can greatly influence the ordination and should be carefully examined.

References

Reuse

Citation

@online{smit,_a._j.2021,

author = {Smit, A. J.,},

title = {Ordination},

date = {2021-01-01},

url = {http://tangledbank.netlify.app/BCB743/ordination.html},

langid = {en}

}