Lecture 5: Light

- Explain what light is, and explore concepts of frequency, wavelength, and energy.

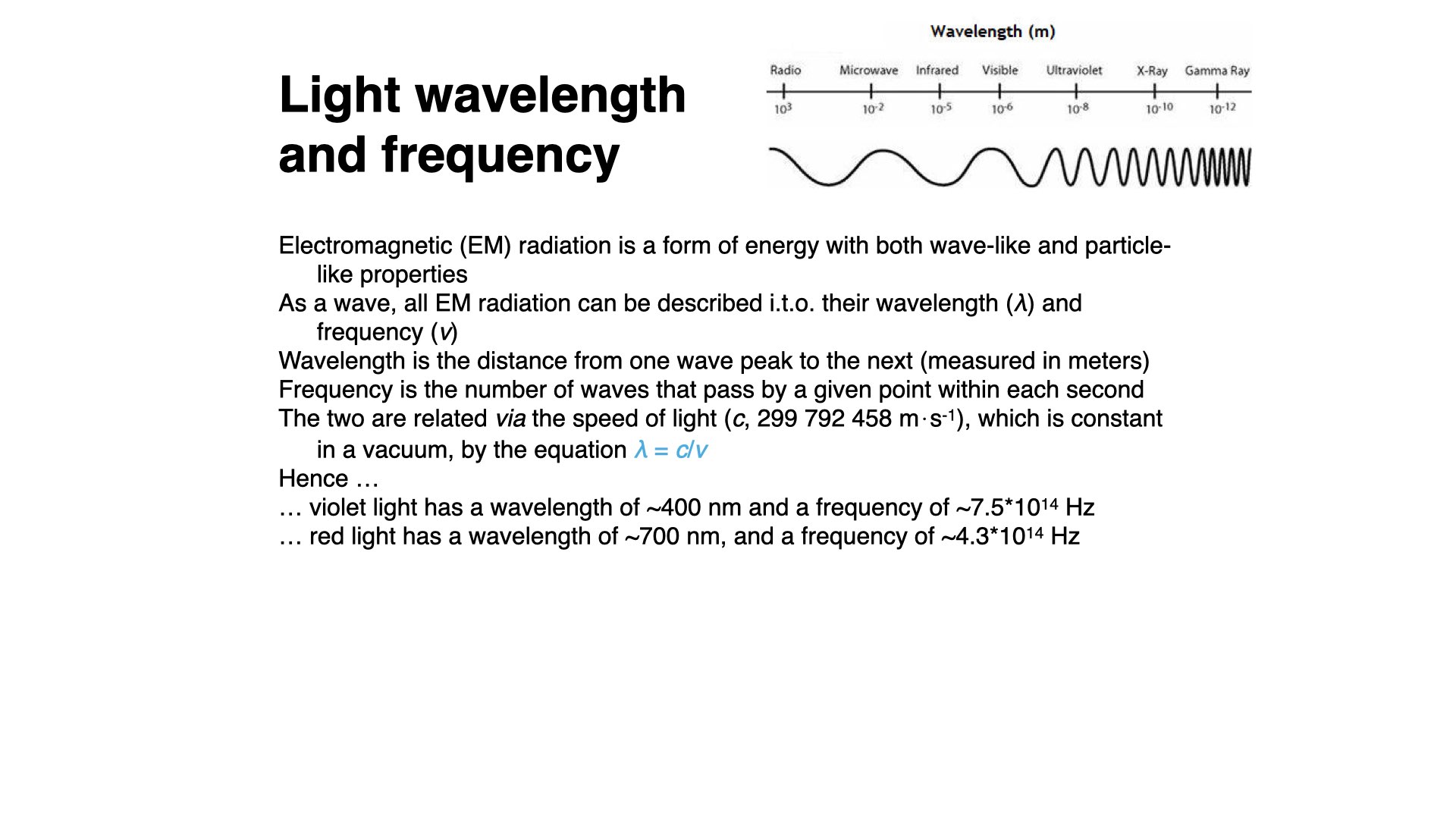

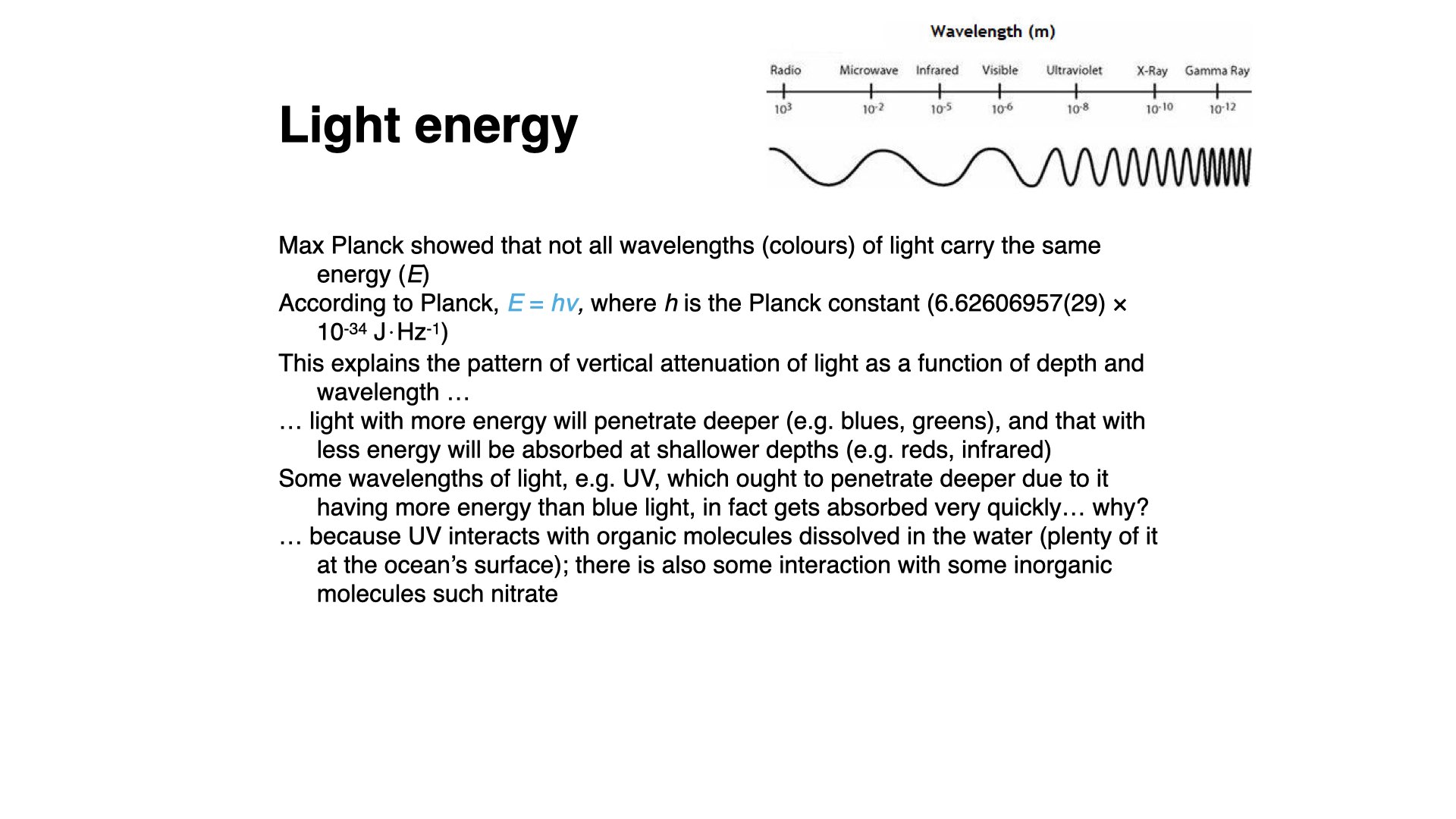

- Describe the electromagnetic spectrum and the different types of light.

- Define the ideas of light quality and quantity.

- Explain how light is measured and the different units used.

- Focus on the quantum nature of light and the concept of photons.

- Discuss the importance of light in ecosystems.

- Explain photochemical equivalence.

- Explain the concept of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) and its importance.

- Describe the different types of light sensors and their applications.

- Describe the Beer-Lambert Law and its applications.

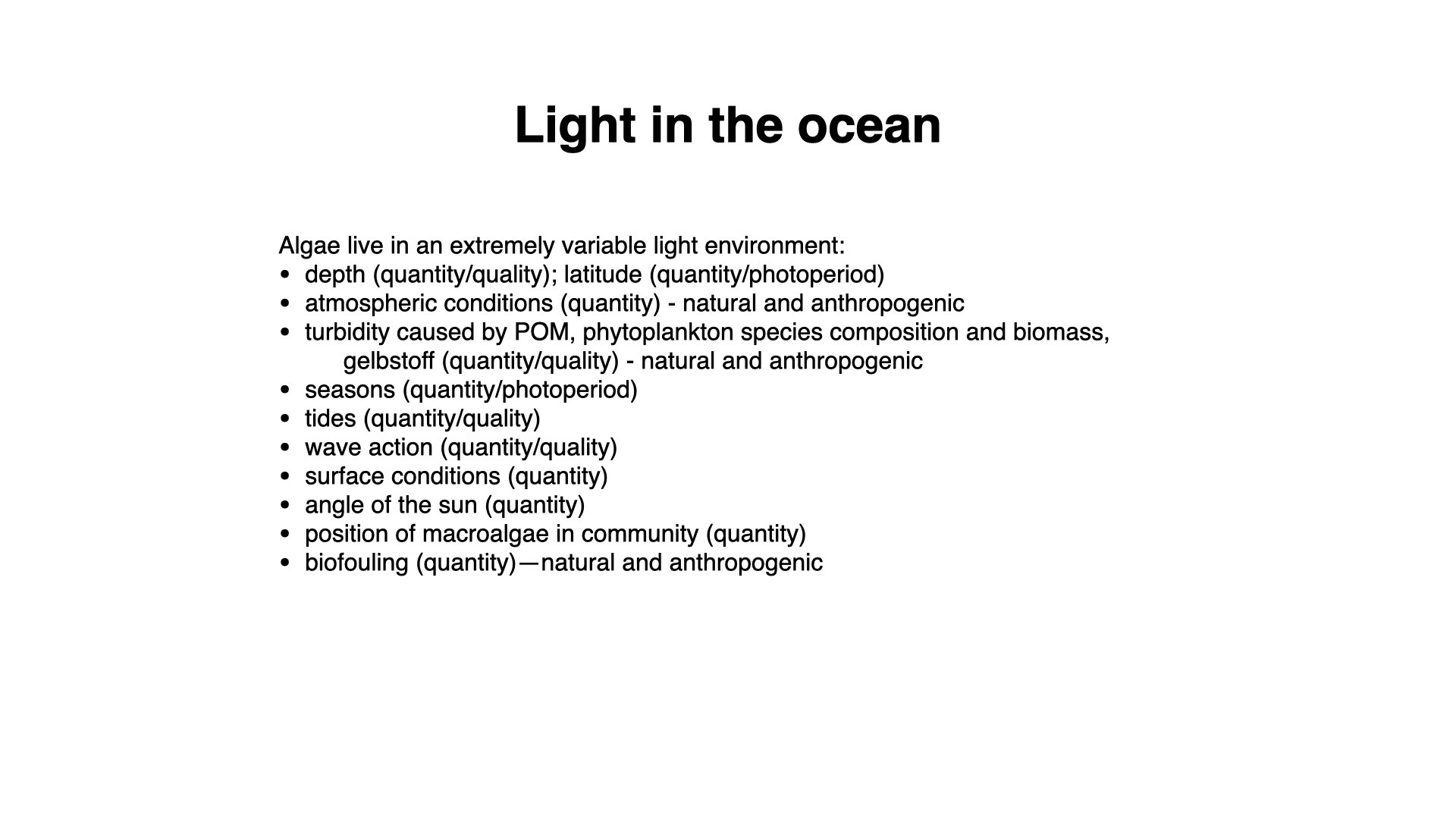

- Explore the properties of the ocean that affect light penetration and variability.

- Explore the properties of the atmosphere and terrestrial systems that affect light availability and variability.

Here I provide you with a thorough understanding of light as a critical factor in ecosystems, particularly its role in plant ecophysiology. The lecture will explore the physical properties of light, including its frequency, wavelength, and energy, and how these aspects interact with biological systems. You will gain insight into how light is measured, the concept of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), and the quantum nature of light through the idea of photons. Finally, you will explore how the properties of terrestrial, atmospheric, and oceanic systems affect light availability and variability, including applications of the Beer-Lambert Law.

- Explain the nature of light by understanding its frequency, wavelength, and energy, and how these properties relate to the electromagnetic spectrum.

- Describe the electromagnetic spectrum and identify different types of light, including visible, ultraviolet, and infrared, and their relevance to biological systems.

- Define the concepts of light quality and light quantity, explaining how each affects biological processes in plants and ecosystems.

- Understand how light is measured and the units used, including those related to light intensity and energy, such as lumens, watts, and photons.

- Explain the quantum nature of light and the concept of photons. This includes demonstrating an understanding of the additive nature of quantum light measurements.

- Explain the concept of photochemical equivalence, and how it applies to the efficiency of light-driven processes in biological systems.

- Understand Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR), its importance to photosynthesis, and how PAR is measured and applied in ecophysiological studies.

- Identify different types of light sensors and their applications in measuring light quantity and quality in various environments.

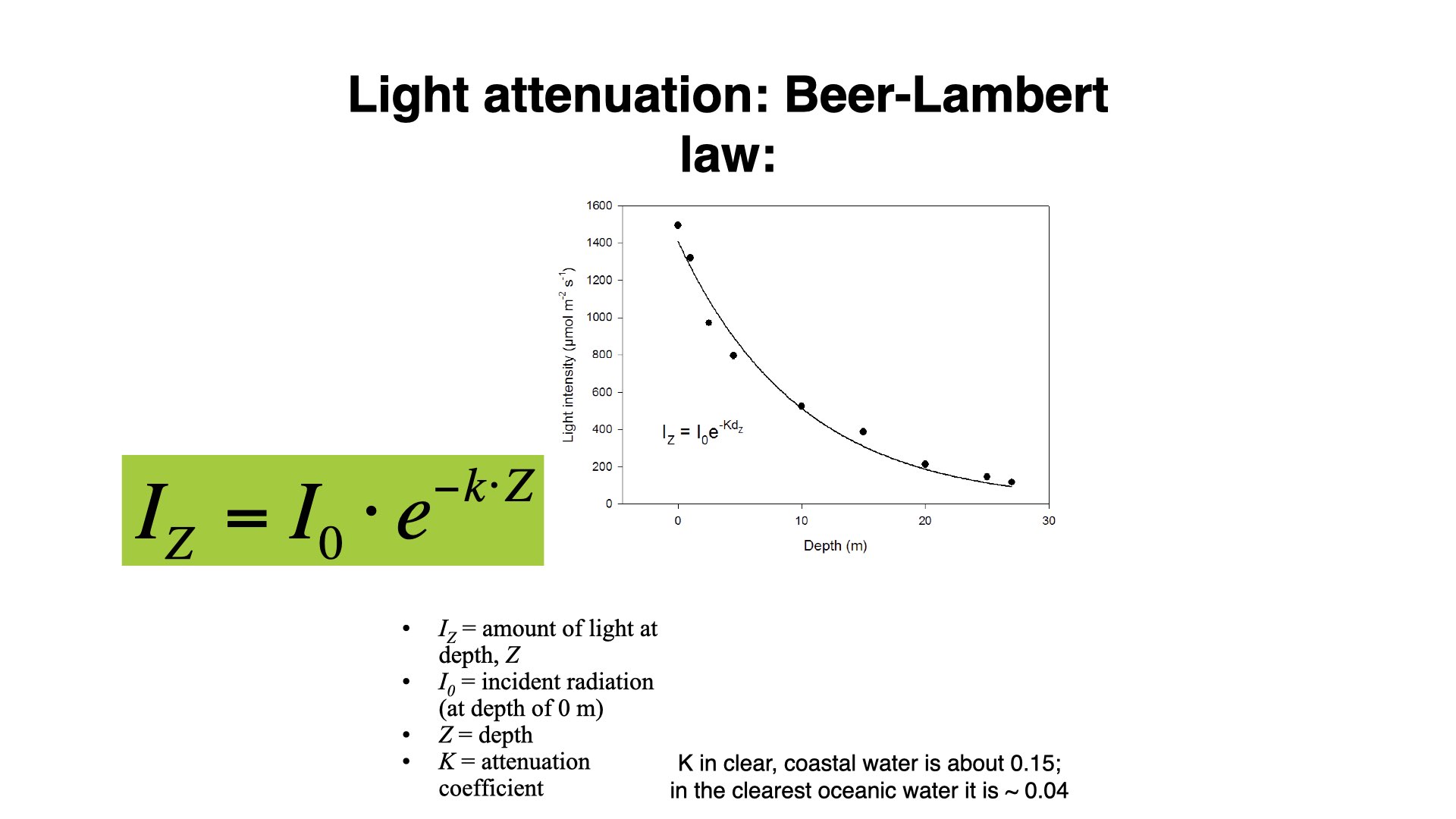

- Describe the Beer-Lambert Law and its applications in understanding light attenuation in different media, such as water and plant canopies.

- Explore the properties of the ocean and atmosphere that affect light penetration, variability, and availability in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, emphasising the environmental factors that influence light absorption and transmission.

1 Introduction: Light as a Plant Stress

Welcome to BDC 223. Today, we are going to continue our lectures on the various stresses that plants experience and the ways in which they interact with their environment. Our focus for today is light. There are several key questions we need to explore in this lecture, and these are also the core points that you will need to understand by the end of our coverage on light.

The main aspects you must grasp include why light is important, and the different properties of light — specifically, the quantity and the quality of light. We must consider what happens to light in both marine and terrestrial environments, and what properties of the world cause light to vary in both quantity and quality in these places. Furthermore, we will look at how we measure light, the effects of light on plants, how plants capture light, the process of photosynthesis, designing experiments to measure photosynthesis, and how photosynthesis relates to plant growth rate. All of these topics will feature in this segment of the lectures.

2 Why Light Is Important to Plants

Light, together with temperature, is perhaps one of the most important factors affecting plants. In fact, as far as plants are concerned, it is the single most important aspect determining many of their properties. It has a drastic effect on photosynthesis. The very reason photosynthesis exists is due to plants’ ability to harvest light, extract radiant energy, and convert it into chemical potential energy, which is then used to sustain growth and drive other aspects of plant productivity.

Light also influences photoperiodisms, which refer to the various endogenous rhythms that plants undergo, mediated and synchronised by either photoperiod or light intensity. There is also photomorphogenesis, the process by which developmental and morphological changes in plants are regulated by light.

Of course, light further influences all manner of ecological interactions. Together with temperature, light has a large consequence for the distribution of plants across the surface of land and within the ocean’s depths.

3 Global and Temporal Variability of Light

Looking at global scales, light is extremely variable across the surface of the Earth, and also across various temporal scales — ranging from seconds, to minutes, to hours, to days, and to seasons. Typically, from year to year, the amount of light tends to be quite stable, but at shorter temporal scales (months, weeks, days, minutes, seconds), it is very variable indeed. We need to understand what causes this variation.

3.1 Quantity and quality of light

It is important to distinguish between the quantity and the quality of light. When referring to the quality of light, we are talking about its colour. The quantity of light is related purely to its intensity, with no distinction made as to whether the light is blue, red, or any other colour. You can have dim red light and bright red light, or dim blue and bright blue sources. Quantity simply means the intensity, regardless of wavelength. Wavelength, on the other hand, is more closely related to quality, or colour.

4 Wavelength, Frequency, and Energy Relationships

Light is just a portion of the electromagnetic radiation spectrum. Human eyes are sensitive to light of wavelength between about

Light possesses both wave and particle properties. The wavelength and frequency of light are measurable and are related to each other via the speed of light (

Short wavelength radiation, like violet light, has high frequency, and red light (around

Energy is also related to wavelength. The energy of a photon is given by

I am not likely to set this sort of calculation in an exam, but it is a possibility for a test or class exercise, so make sure you understand the relationship.

There are also shorter wave portions in the UV spectrum (

Infrared radiation, above about

5 Visible Light and Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR)

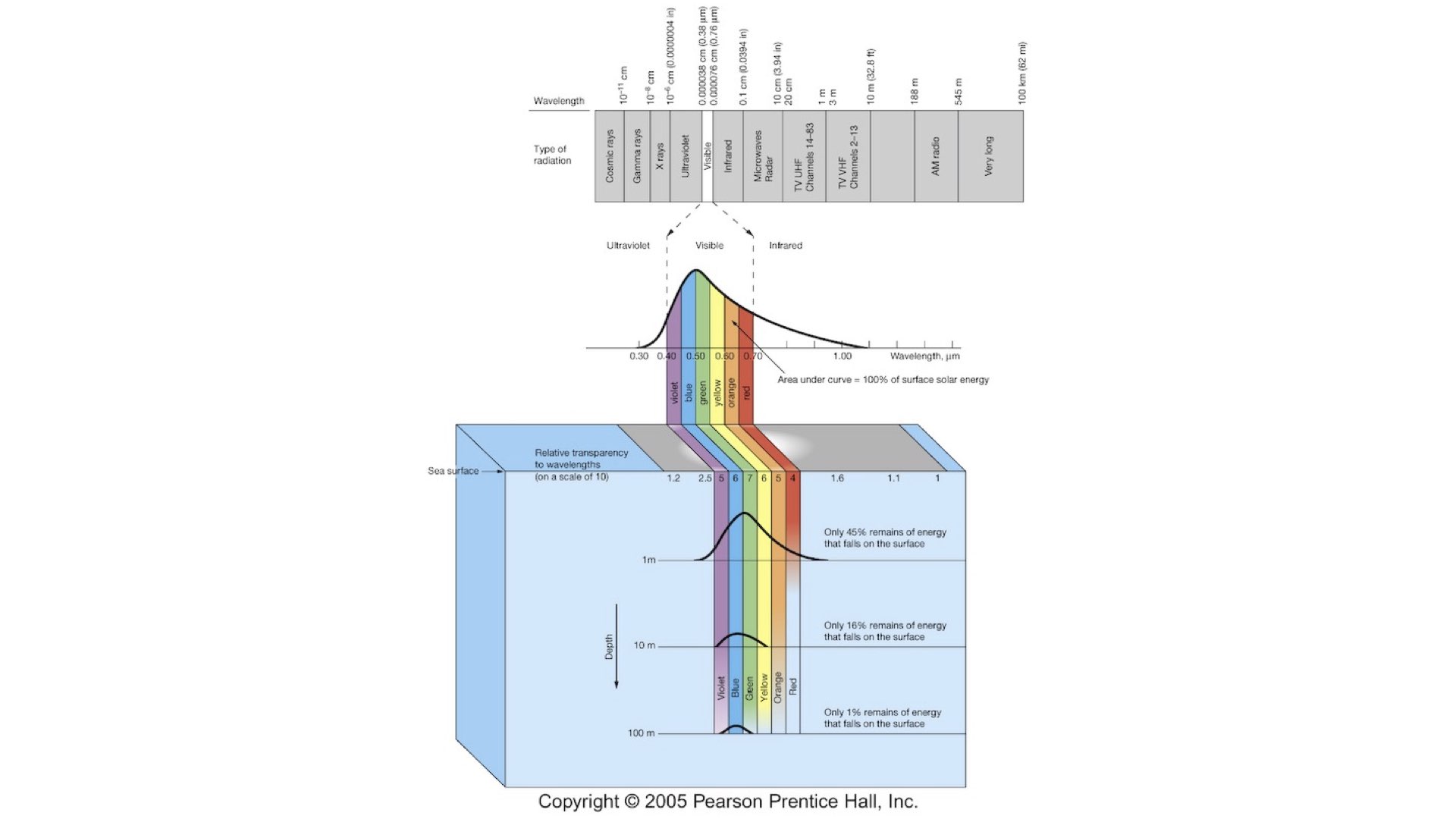

6 Light Interactions in the Marine and Terrestrial Environments

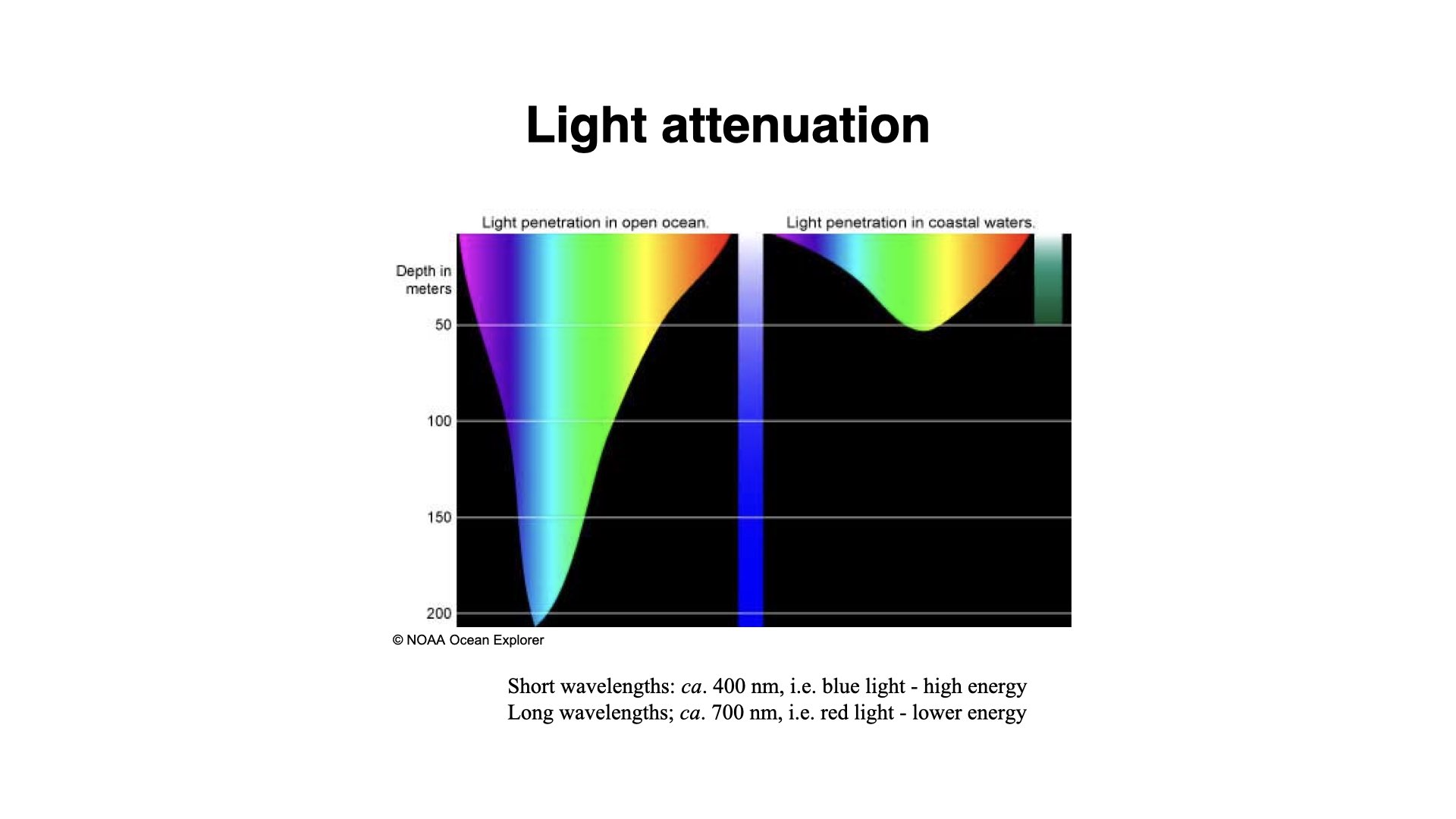

When light falls on water, some of the longer wavelengths, such as reds, and to a lesser extent, some blues, are absorbed by the water. Red light has lower energy and does not penetrate as deeply into the water column as blue light, which is higher in energy and penetrates much deeper into the ocean.

On land, there is not nearly as much variation in light quality as there is in the marine environment. However, it is crucial to understand what happens to light under water. Red light is absorbed first, and blue light can travel much deeper. As blue light is scattered in the water column, that is why when you look down into the ocean or put your head underwater, the world appears blue. Similarly, this is why the Earth looks blue from space — the blue light from the ocean surface is being scattered, while red light is absorbed. The red light also warms the ocean surface.

For example, if you take a white plate or a piece of white paper underwater and dive down five or ten metres, it appears blue because there is a predominance of blue light at those depths.

7 Light Penetration and Beer-Lambert Law

The extent to which light diminishes as we go down a water column is called attenuation. This is described by the Beer-Lambert Law, which provides us with an equation to calculate the light intensity at a given depth (

In coastal environments, the attenuation coefficient is generally high, due to increased turbidity — lots of particles and suspended solids absorbing and scattering light. In open ocean waters, this coefficient is much lower, allowing light to penetrate deeper due to clearer water.

You will certainly be assessed on your understanding of the Beer-Lambert Law, both in written assessments and practicals where you may need to apply this equation to actual data.

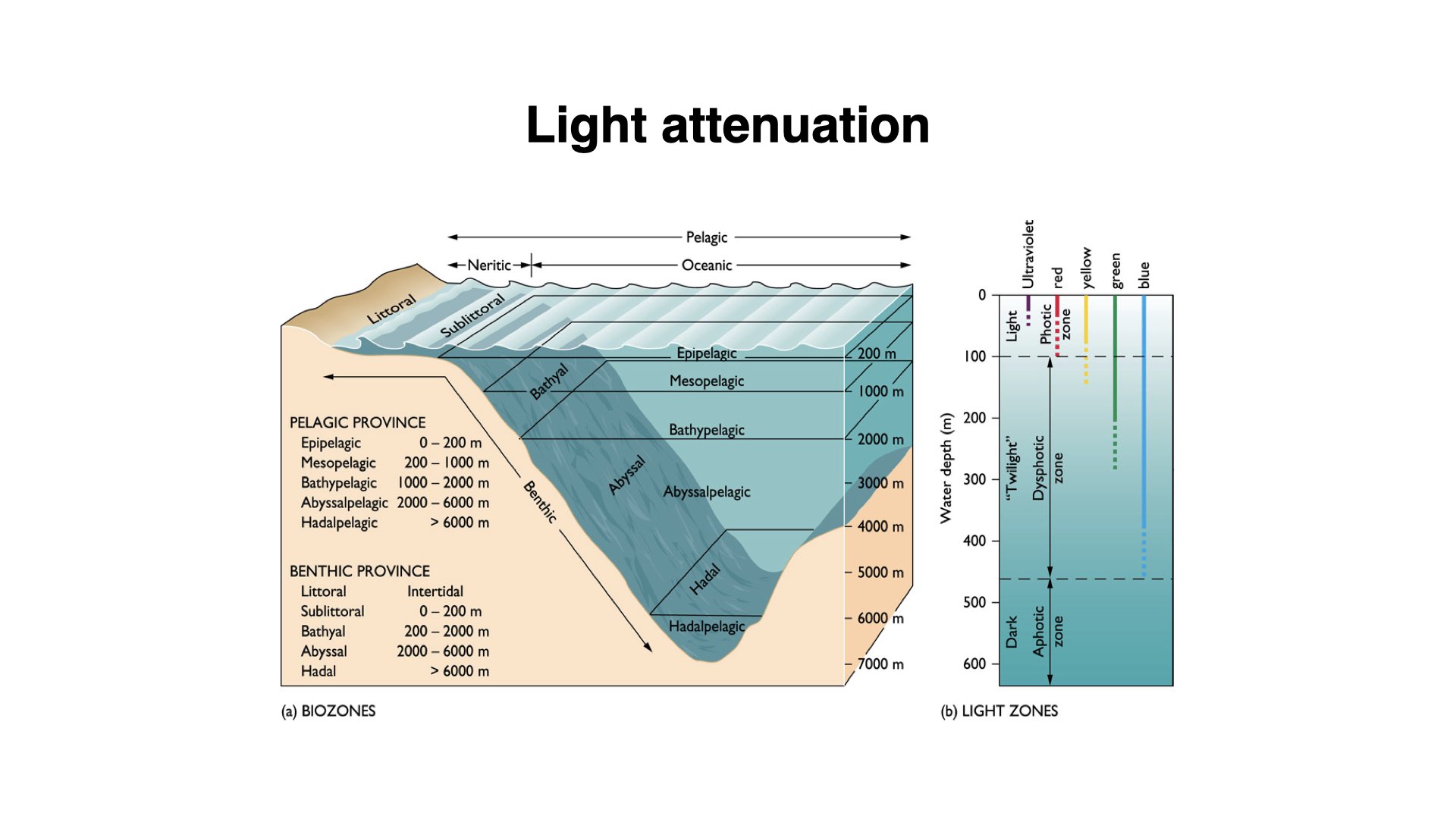

8 The Structure of the Ocean: Light Zones

As light penetrates the ocean, its intensity decreases and its quality changes with depth. At about

At about

About

The warmest water is at the upper layers — top

9 Coastal Vs. Open Ocean Light Penetration

There is a distinction between coastal water and open ocean water in terms of light penetration. In coastal waters, due to higher amounts of total suspended solids (TSS) and turbidity resulting from riverine input, human activity, pollution, and erosion, light does not penetrate much beyond

TSS in coastal areas absorbs and scatters light more, resulting in diminished light intensity and a shift in quality — colours change as certain wavelengths are more heavily absorbed or scattered. Despite this, blues and greens can penetrate furthest in the open ocean, as fewer particles are available to absorb them.

10 Measuring Light

10.1 Quantum measurements

Scientifically, we measure light using a quantum approach — the number of particles or ‘quanta’ (photons) of light falling on a given surface per unit time and per unit area. The standard unit is the micromole per metre squared per second (

This quantum measurement is additive—if

Importantly, quantum measurements do not distinguish between colours of light. Every quantum counts equally, regardless of whether it is red, blue, or any other colour. Thus, quantum measurements are agnostic regarding the quality of light.

10.2 Example typical ranges

In the tropics, midday full sunlight yields about

10.3 Light sensors

To measure photon flux density, we use light meters equipped with quantum sensors. There are two main sensor types:

- Spherical sensors: These measure light falling from all directions around the sensor — it is immersed in a sphere and integrates all incident light.

- Cosine-corrected sensors: These are flat disks, measuring light from a single primary direction and ignoring off-angle contributions.

Both sensor types have their place in plant biology, and we will encounter them in practicals.

10.4 Other units and approaches

There are other units for measuring light as energy, but these are less useful to us as biologists, except perhaps in the context of heat loss or gain. Such units, and others like foot candles or lux, are designed more around human visual sensitivity (biased to yellows and oranges), or for industrial and interior lighting, rather than scientific plant research.

11 Effects of Different Wavelengths on Plants

- Ultraviolet (<

- Infrared (>

- Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR): The relevant range for photosynthesis is between about

12 Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR)

PAR is the essential definition to remember. It is the segment of light — between

Reuse

Citation

@online{smit,_a._j.,

author = {Smit, A. J.,},

title = {Lecture 5: {Light}},

url = {http://tangledbank.netlify.app/BDC223/L05-light.html},

langid = {en}

}