Lecture 1: the Limits to Life

- Limits to life in the solar system.

- Earth is the only planet with life as far as we know.

- Life evolved and diversified.

- Our ancestors.

- Human societies developed during the Holocene.

- Human impacts on all life on Earth.

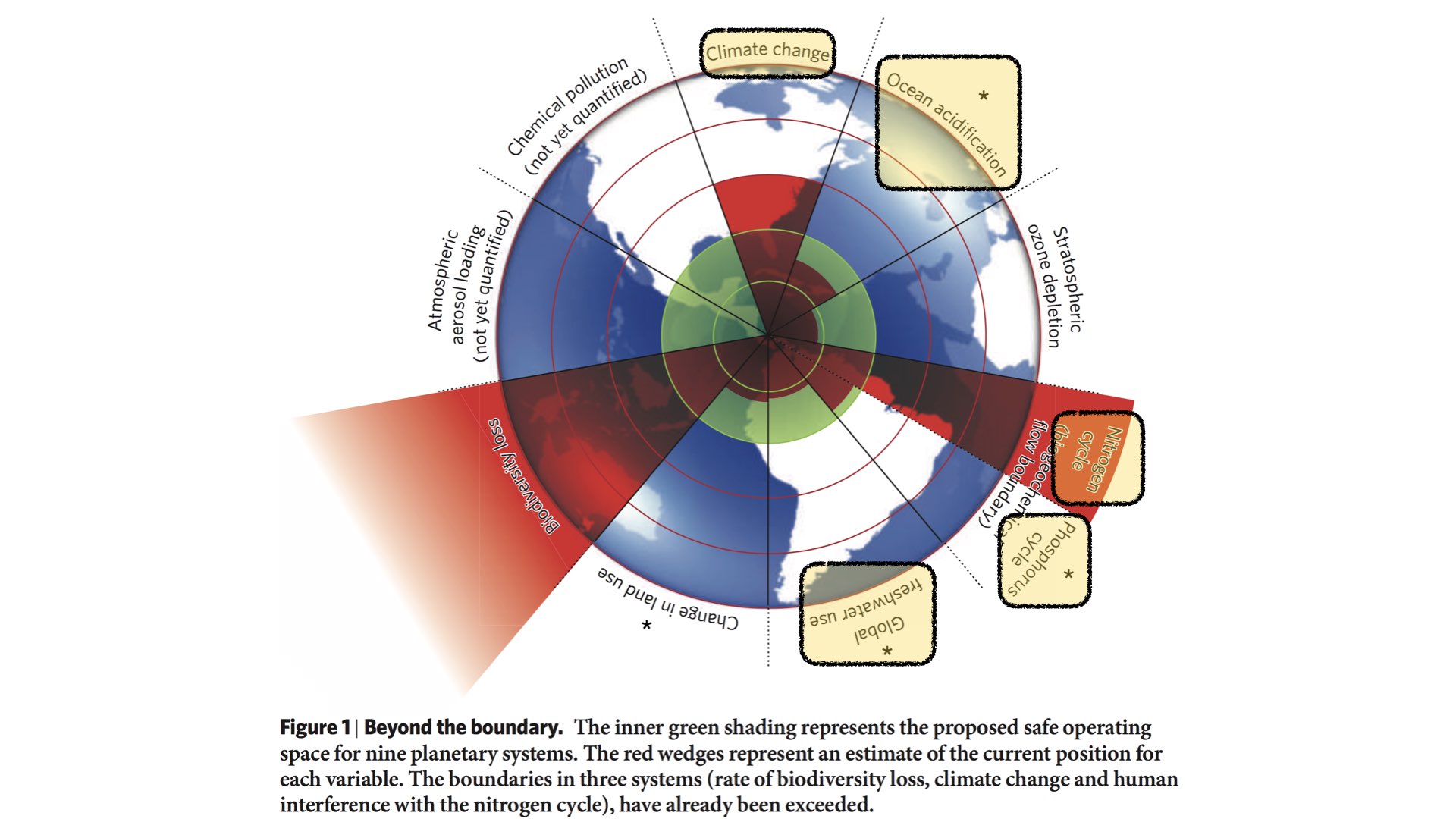

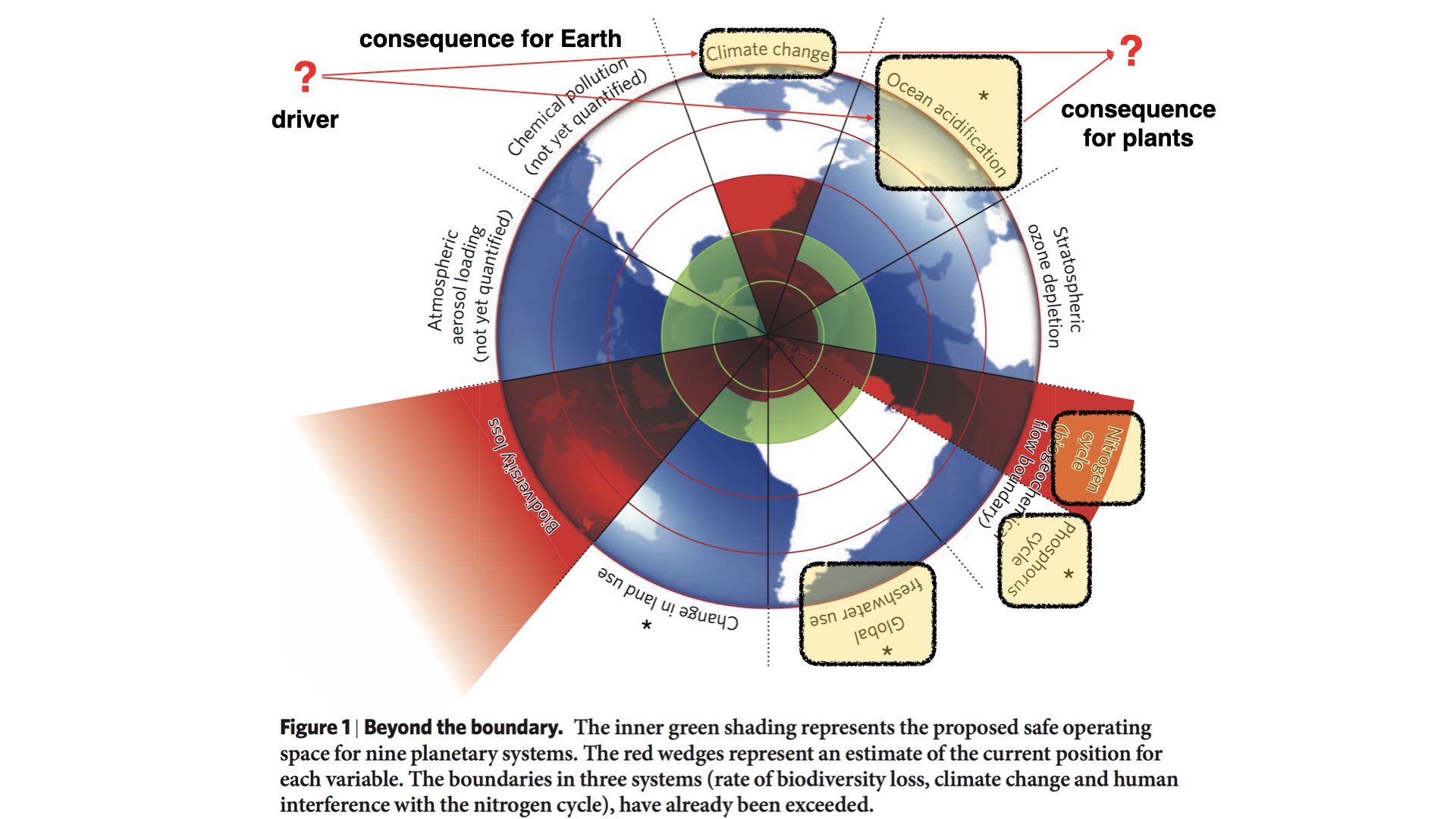

- Exceeding planetary boundaries.

- Consequences for all life on Earth, including that of plants.

This lecture will provide students with an understanding of the concept of planetary boundaries and the significant role humans play in altering Earth’s environmental systems. I will offer a broad overview of how life on Earth has evolved over billions of years, and highlight the immense timescale involved in the diversification of life. I emphasise how humans, despite their relatively recent appearance, have profoundly affected the planet. By examining previous planetary-scale events, such as the Great Oxidation Event, we will explore how certain forms of life have historically altered Earth’s systems and contrast these with the current impact of human activity. This will lead to a discussion on the consequences of exceeding planetary boundaries, particularly focusing on how these changes affect plant life.

By the end of this lecture, you will be able to:

- Explain the concept of planetary boundaries and understand why they are critical for maintaining the stability of Earth’s systems, particularly those that support life.

- Describe the evolutionary timeline of life on Earth, highlighting the immense time it took for life to diversify and comparing it to the brief period in which humans have existed.

- Identify key planetary-scale events, such as the Great Oxidation Event, that were caused by the super-abundance of certain life forms, and explain their impact on Earth’s atmosphere and ecosystems.

- Understand how human activity differs from natural events in terms of its rapid and wide-reaching impact on planetary systems, especially through the capacity for knowledge, learning, and technology.

- Evaluate the impact of exceeding planetary boundaries on all life, with particular emphasis on the implications for plant ecophysiology and the survival of diverse ecosystems.

- Reflect on the role of human societies in shaping Earth’s current environment, particularly during and after the Holocene, and recognise the critical need for sustainability to prevent further ecological damage.

1 Introduction: Contextualising Plant Ecophysiology

Today we will cover the first portion of the lecture content. Yesterday was an introduction to the module; today, we need to set the scene within which we will contextualise the plant ecophysiology component of your ecophysiology module.

Generally, the way I like to do this is to start by giving you a brief overview of the state of the world and the place of people in it. It is because of people that the various stresses that plants experience exist. People, because they are so numerous, exert a whole range of different influences on the planet, and I would like to give you an overview of how that came to be.

I will call this set of lectures, or these slides, “The Limits to Life”, because there are certain boundaries within which life can operate smoothly. As we move outside those boundaries or exceed some of these limits, life becomes increasingly difficult for all of us, including the plants we are mostly interested in throughout this module. Human influence on the planet drives these exceedances.

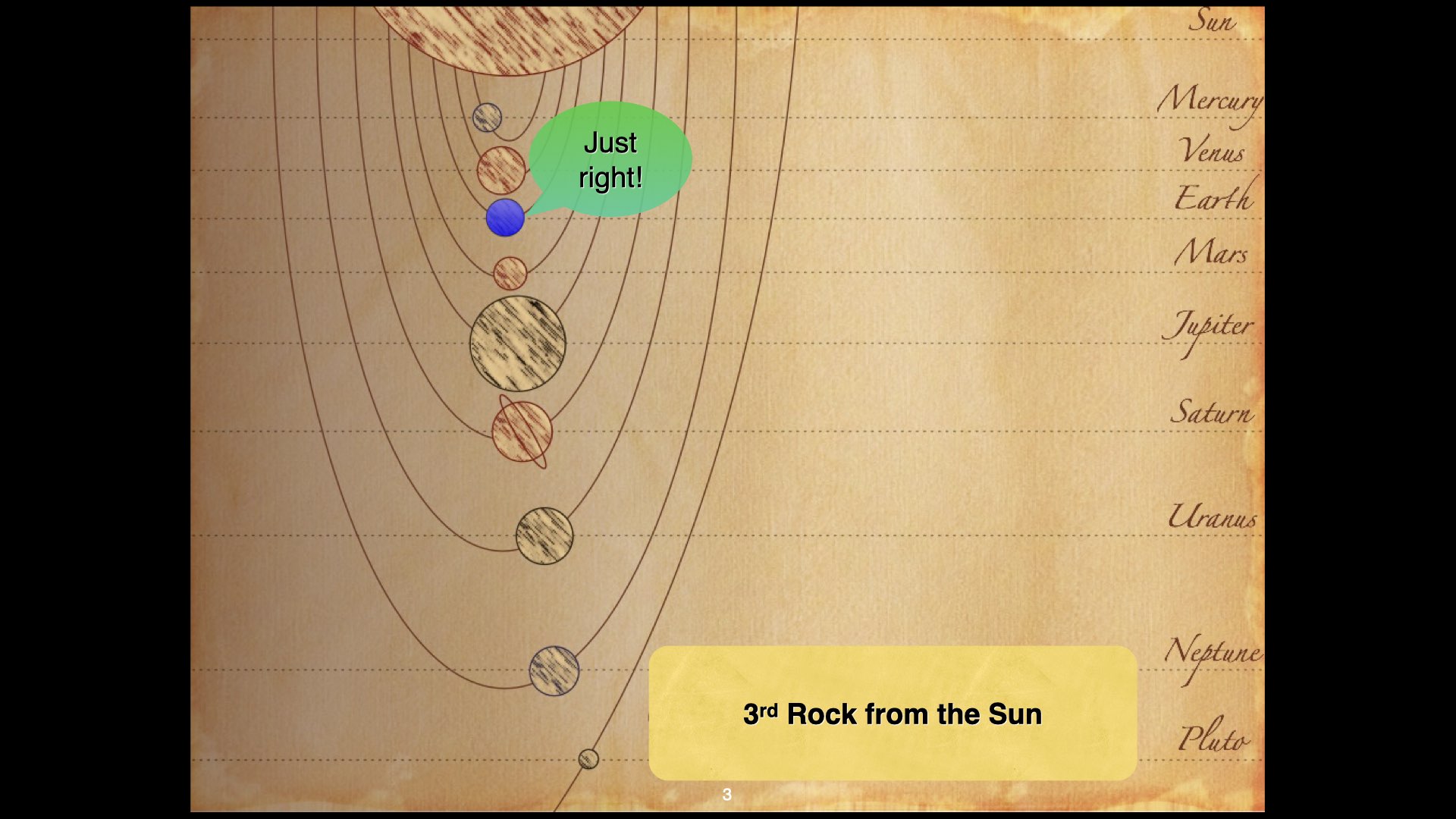

2 Earth’s Place in the Solar System

As you know, Earth is the third planet from the Sun, and that position is significant. The relevance of our position in the solar system, between Venus and Mars, is that it creates a perfect set of conditions where everything is just right for life to exist. This is not true for Venus, which is the second planet, nor Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun [attention: Mars is the fourth planet, not the third; Earth is the third]. Venus is closer to the Sun, so it is too hot; Mars is further away, and it is too cold. So, like Goldilocks, Earth is just right.

It is just right because water can exist in the three phases necessary for the existence of life: as a liquid, as ice, and as vapour — clouds. Without water present in all three phases, the hydrological cycle as we know it could not operate. This sets a series of limits within which life persists, with the range of temperatures on the planet being an important parameter. Even though water exists as a liquid between

3 Shifting Limits: Anthropogenic Change

This particular set of limits is shifting; it is not constant. It has not been constant forever, but now, in more recent times — at least since the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s — the rate at which those limits are changing is accelerating. That is called climate change. I will talk a bit more about this later on in the module, and also on Thursday, when I see you again, as there is an entire module focused on climate change, if I remember correctly.

4 Earth from Space

In 1990, Carl Sagan persuaded NASA to have the Voyager 1 spacecraft — then more than six billion kilometres from Earth — turn its camera back toward our planet. The result was the now-famous Pale Blue Dot. For the first time, humanity saw Earth not as a huge globe but as a single pixel of light suspended in the cosmic dark. That faint speck highlighted the planet’s singularity: in all the vastness of the solar system, Earth was the only known home for life.

In the image, though Earth is almost imperceptible, we know what lies within it: water in all three of its states — clouds forming from vapour, oceans of liquid spanning the surface, and polar caps of ice. The vast Pacific occupies much of the visible face of the planet, with familiar landmasses like Australia positioned at its edge.

That perspective reshaped how people thought about our world. It revealed Earth as rare, fragile, and utterly irreplaceable — the only place where human life can exist. There is a beautiful video in which Carl Sagan himself speaks about this vision, reflecting on the fragility of life on our pale blue dot.

5 Viewing Earth as a System

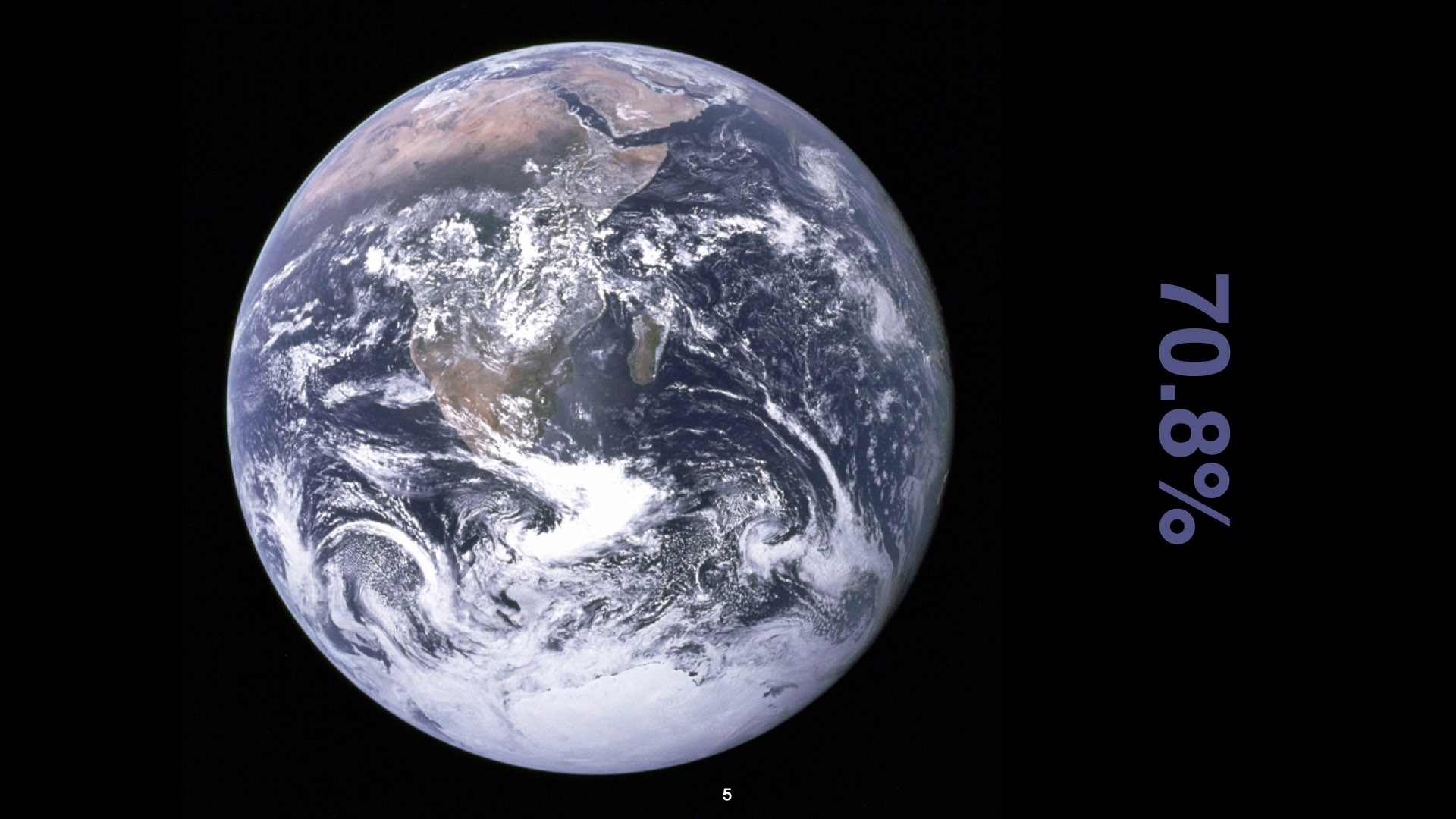

This module will focus on viewing Earth as a whole system, rather than on individual plants or animals. We will discuss how the Earth system sustains life, and the necessary conditions for life to persist. For instance, if you look down onto South Africa, with most of Africa visible on the top left and Antarctica below, you will see the swirling clouds of the large atmospheric gyres, which move water vapour and air around and constitute our climate systems.

One critically important aspect of the Earth is the oceans. Without the oceans, life would not exist as we know it.

Ideally, we should not call the planet “Earth” but rather “planet ocean”, as it is predominantly covered by ocean water.

6 Demographic Changes and Global Population

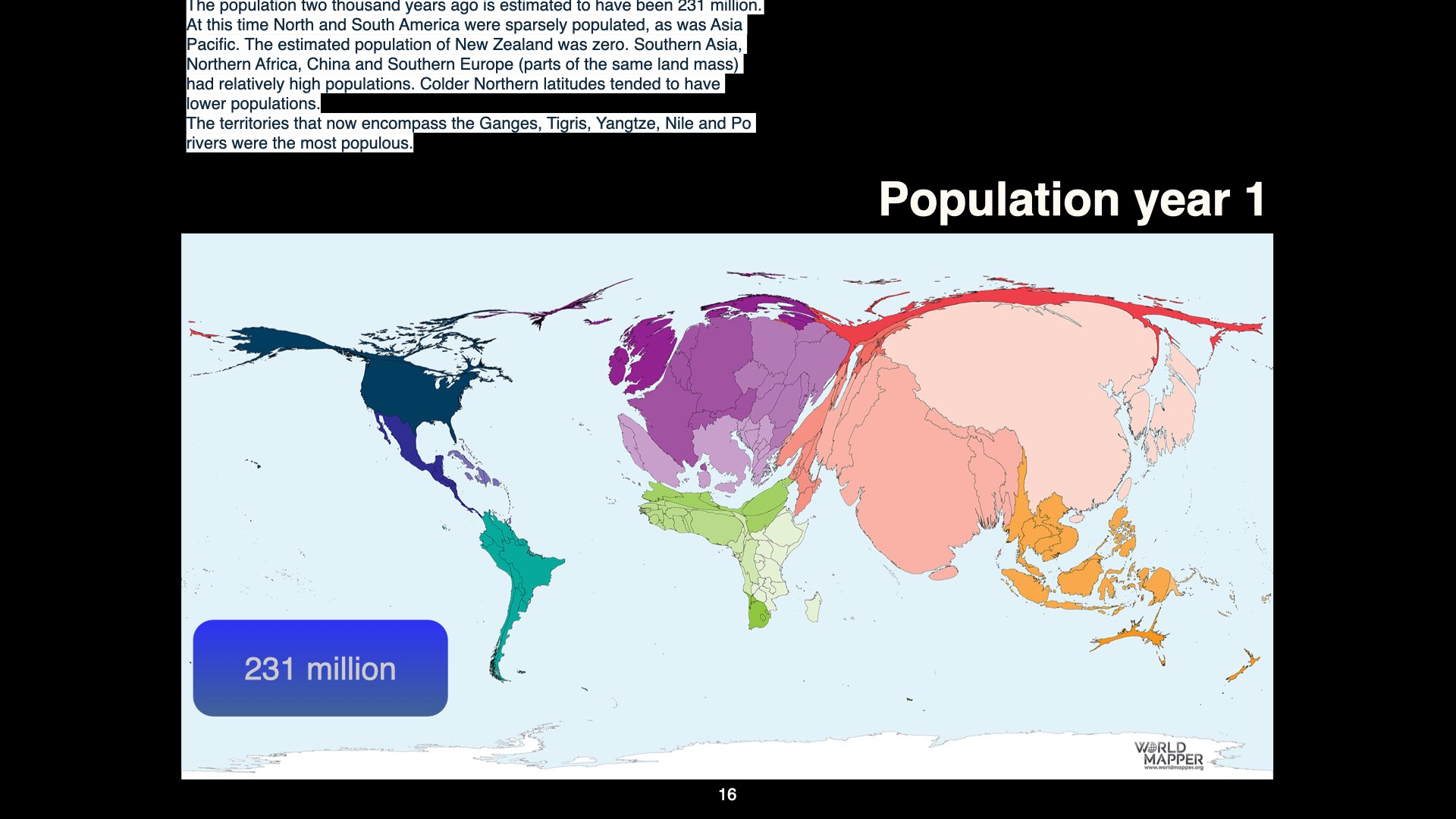

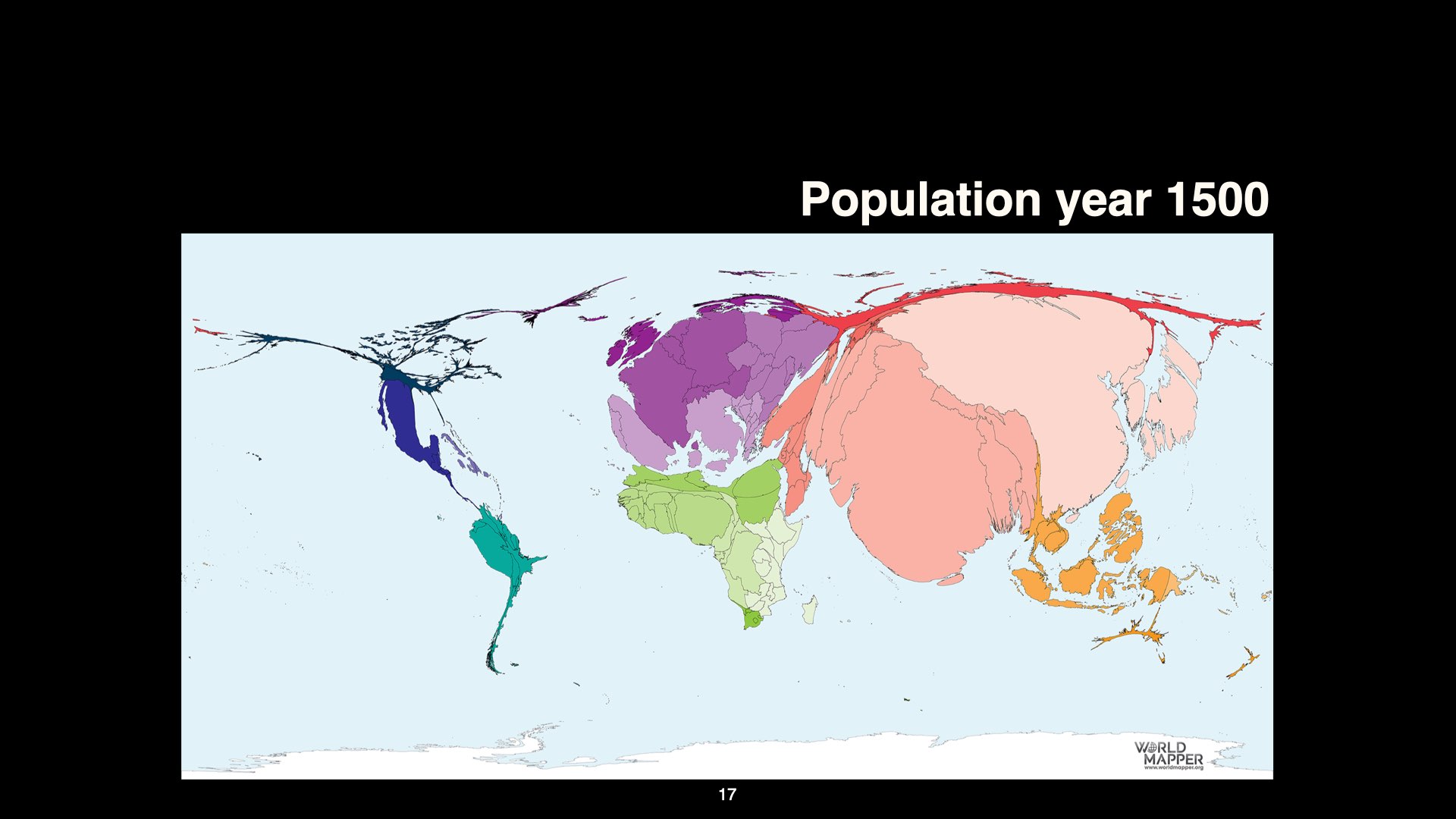

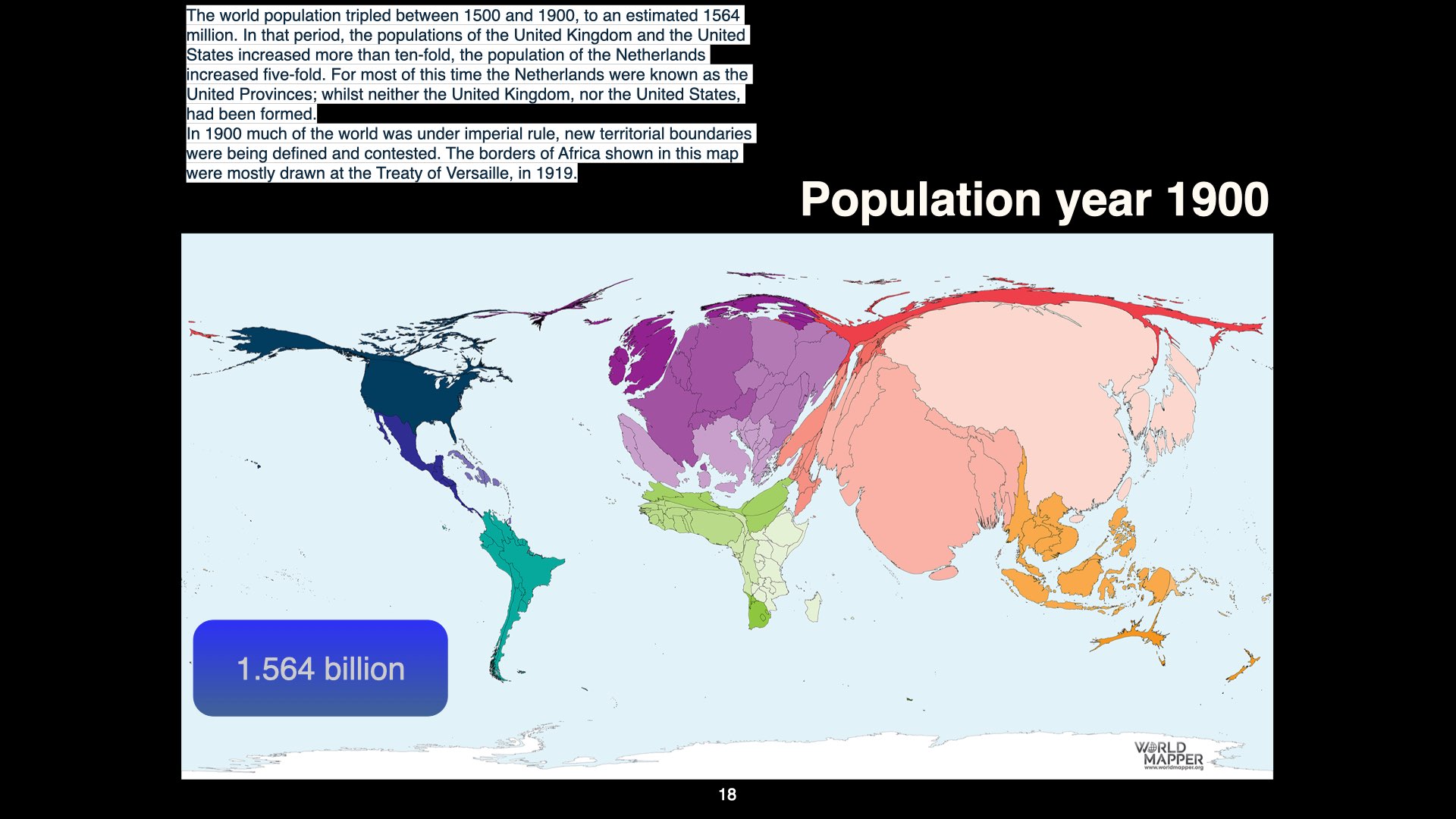

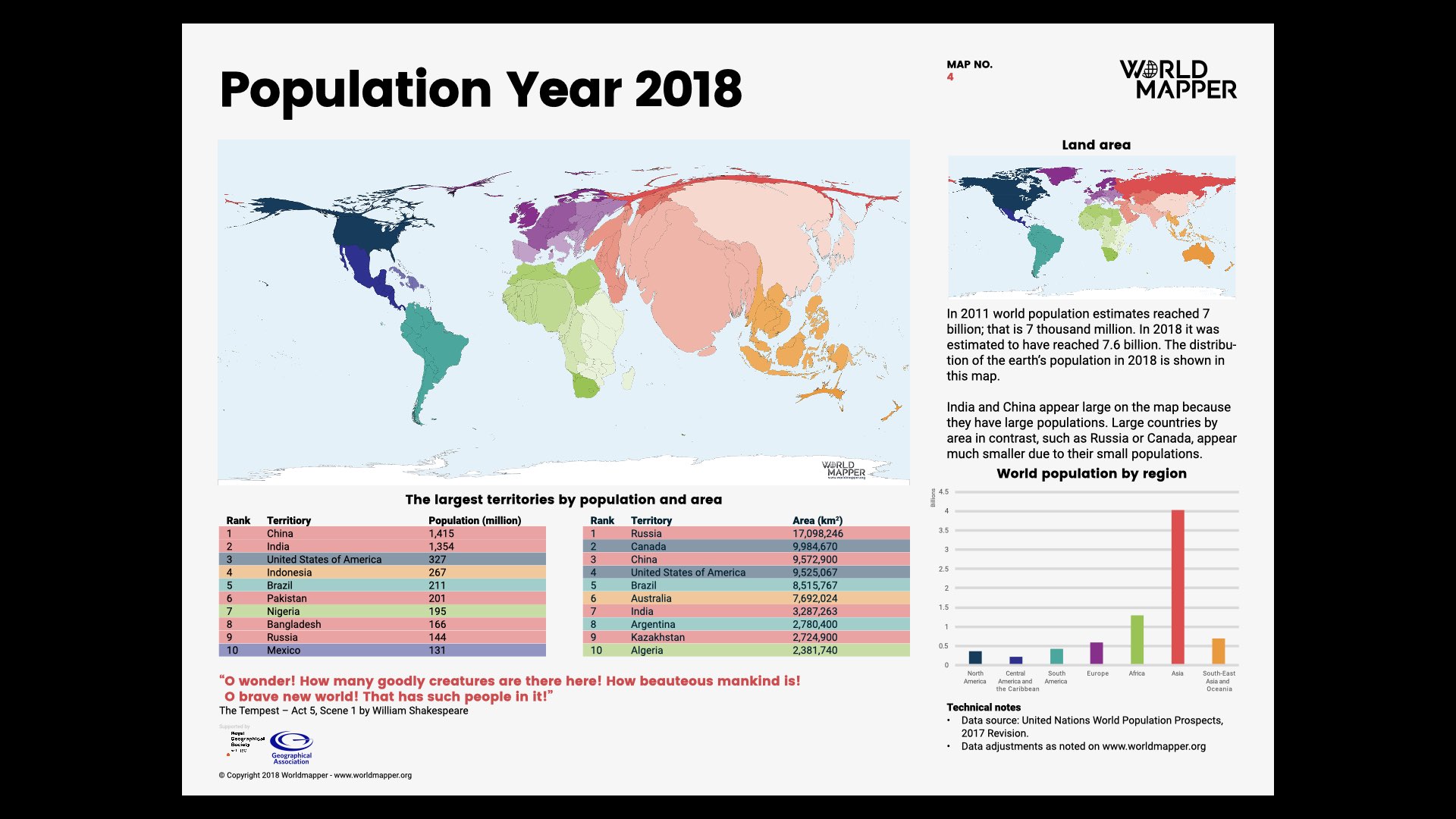

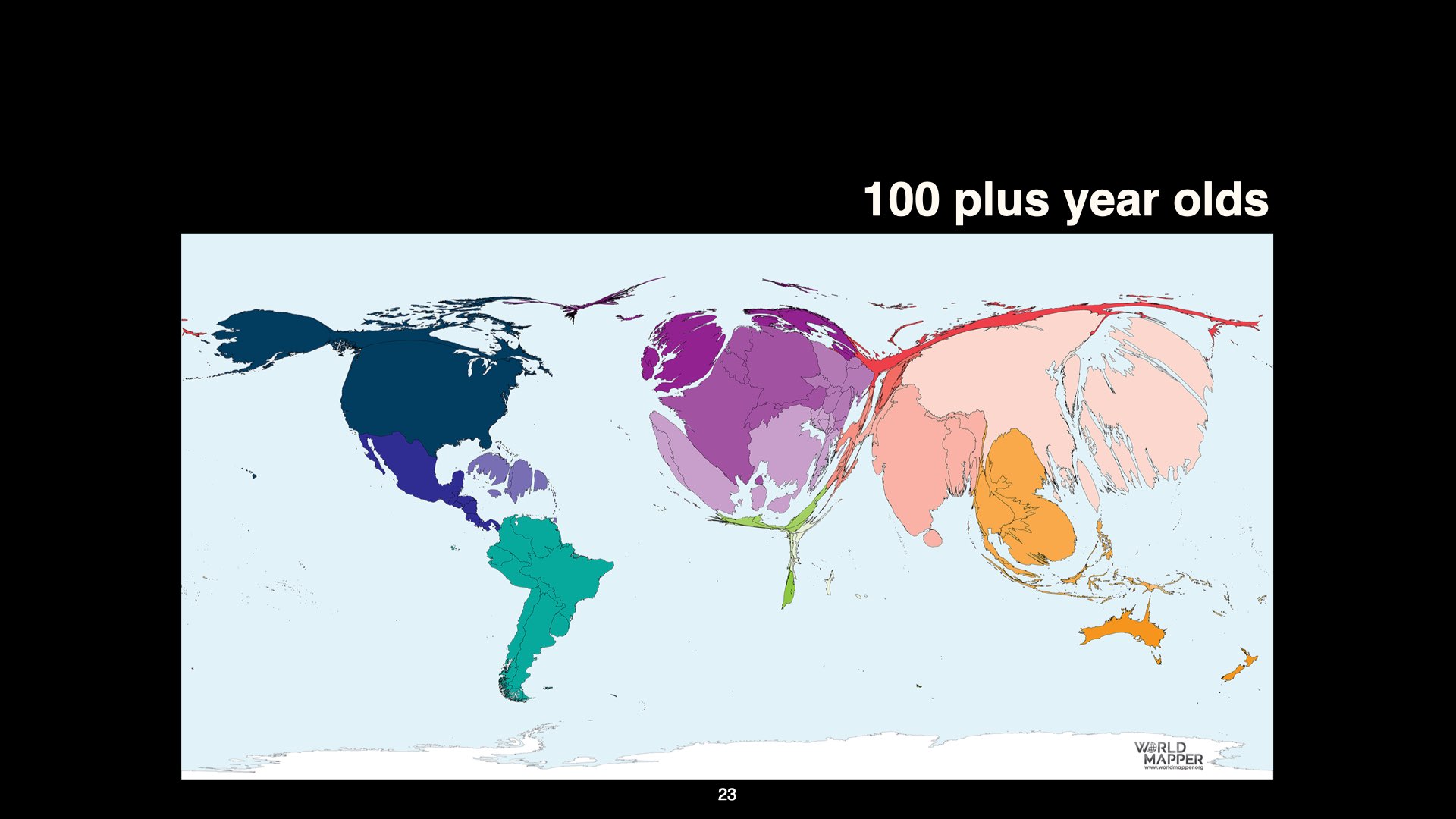

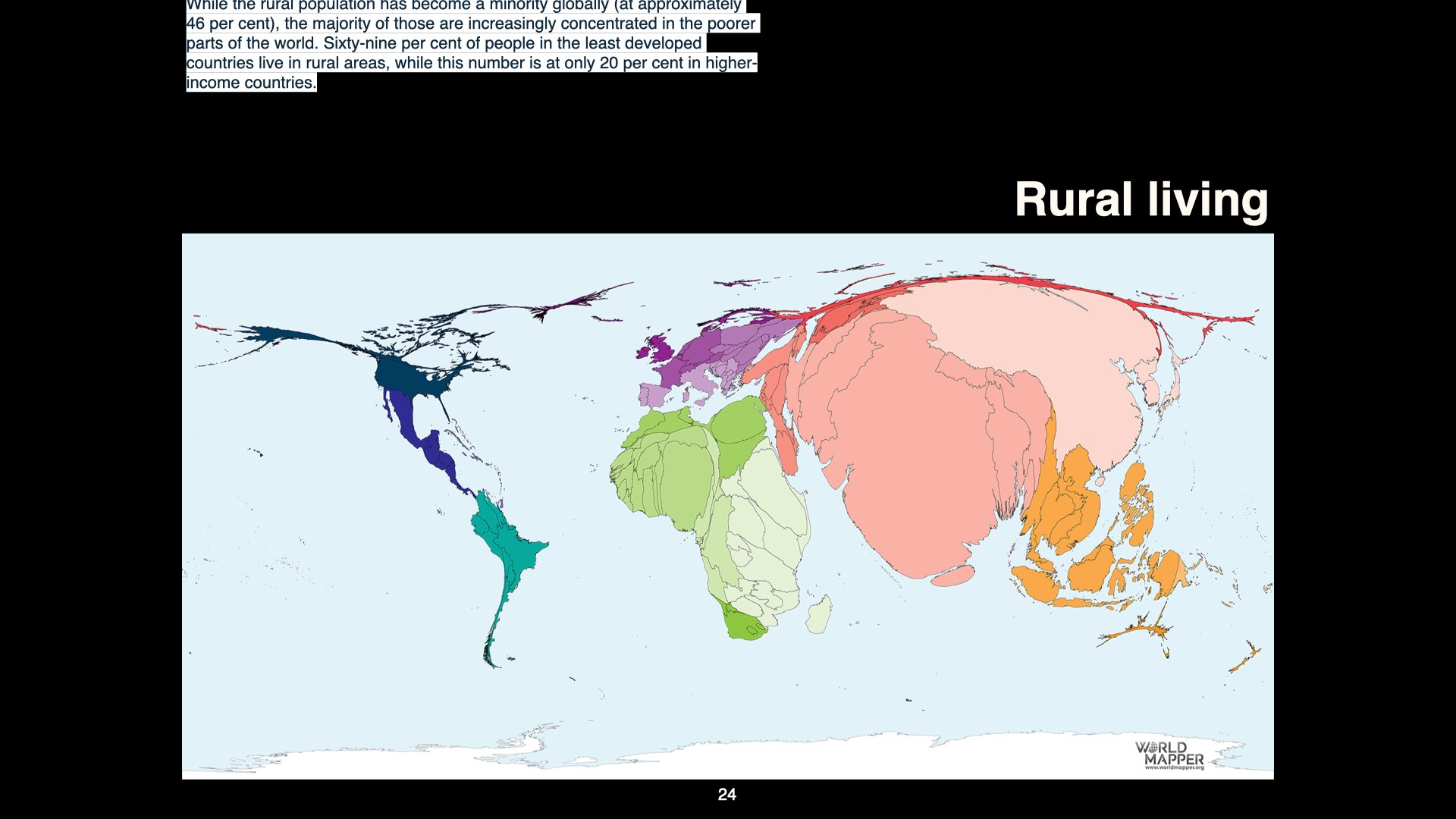

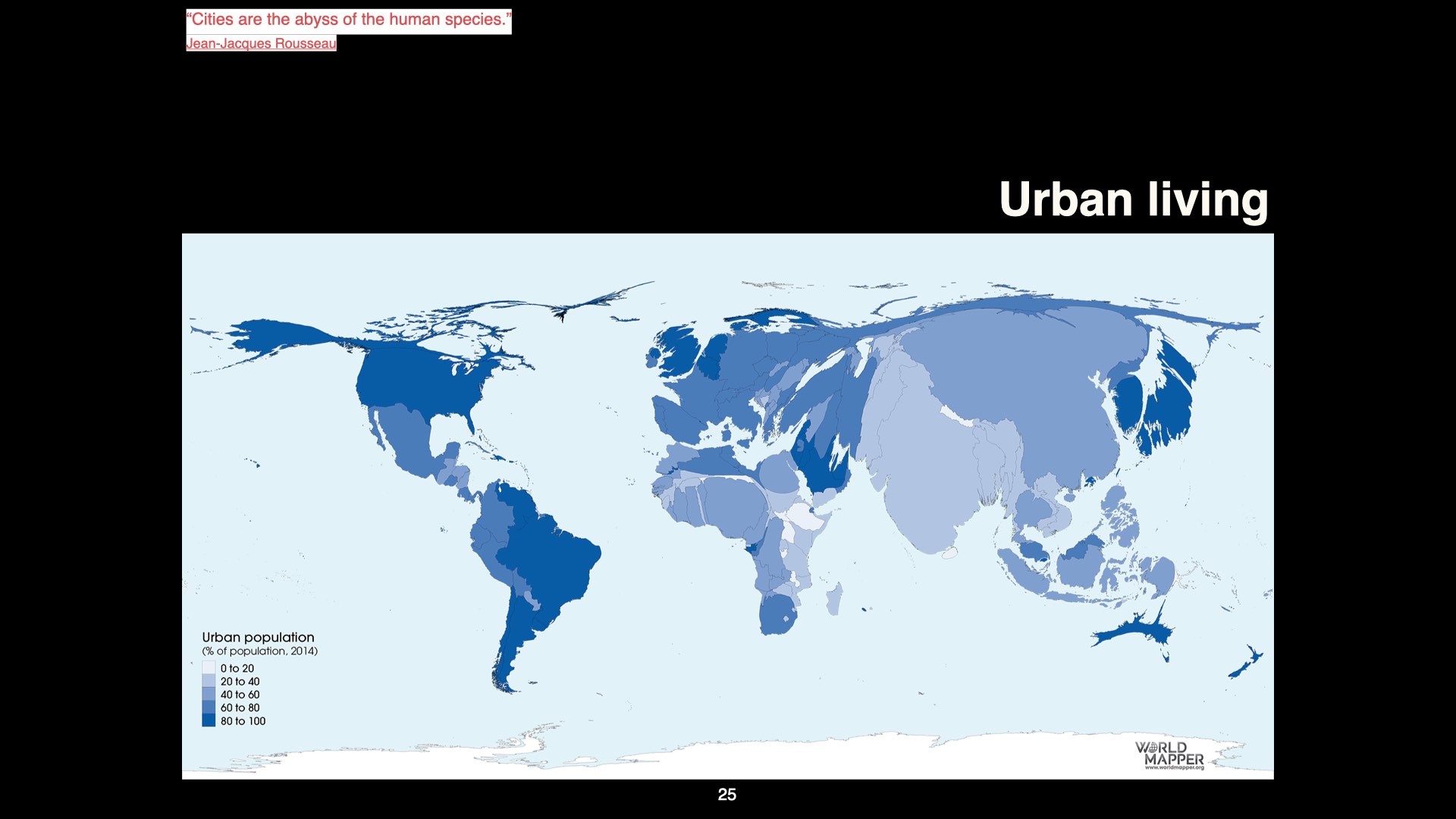

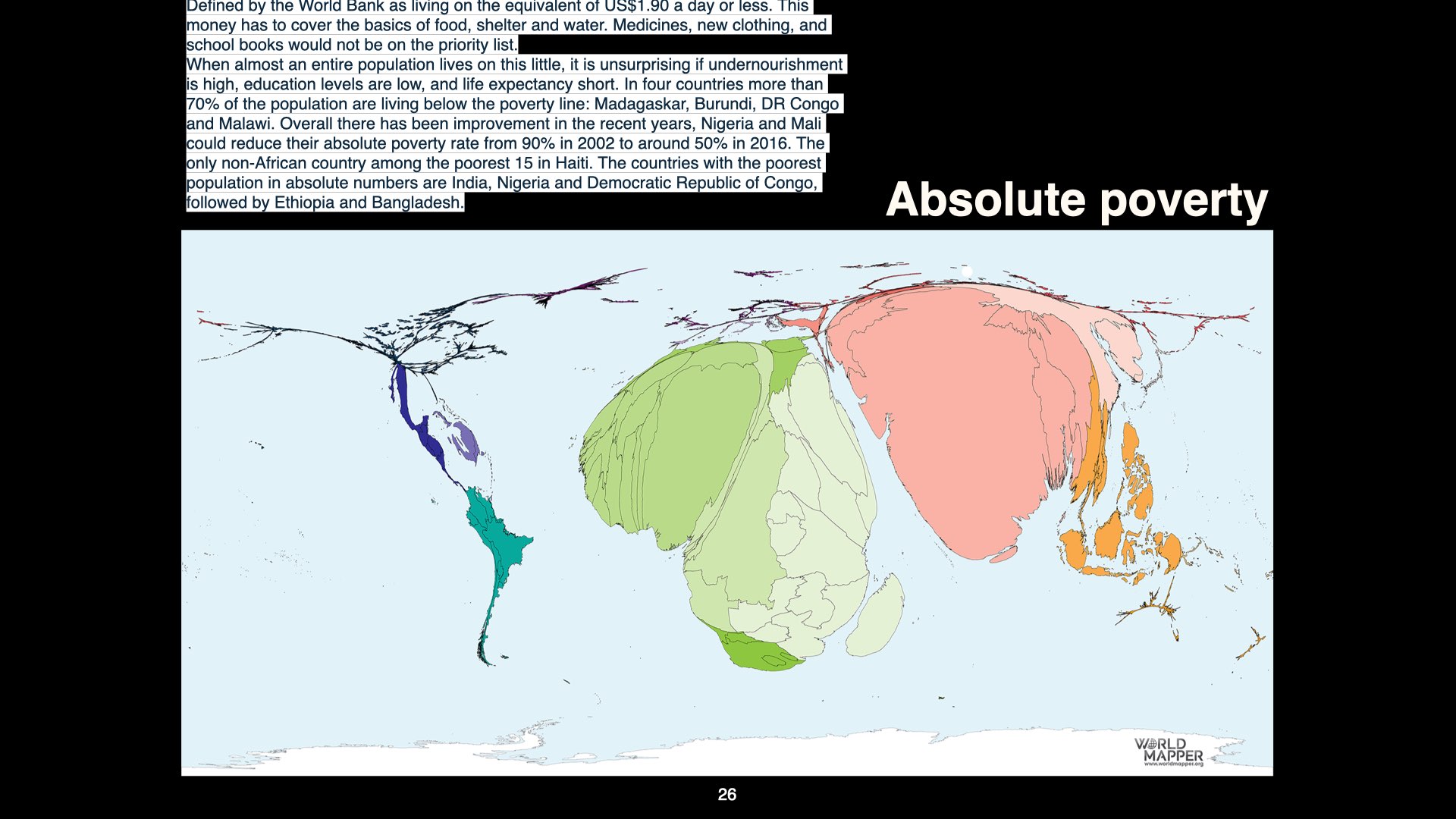

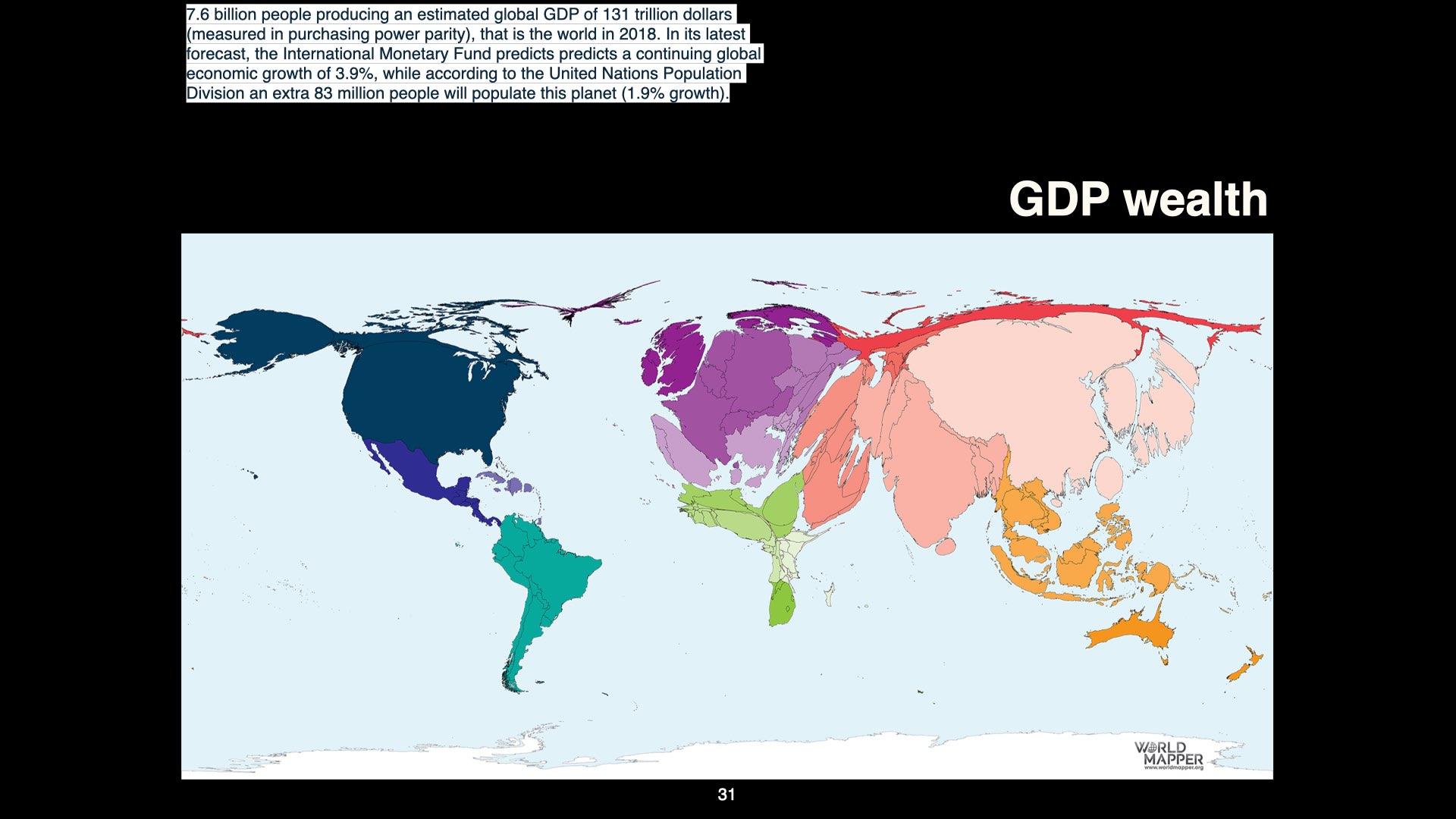

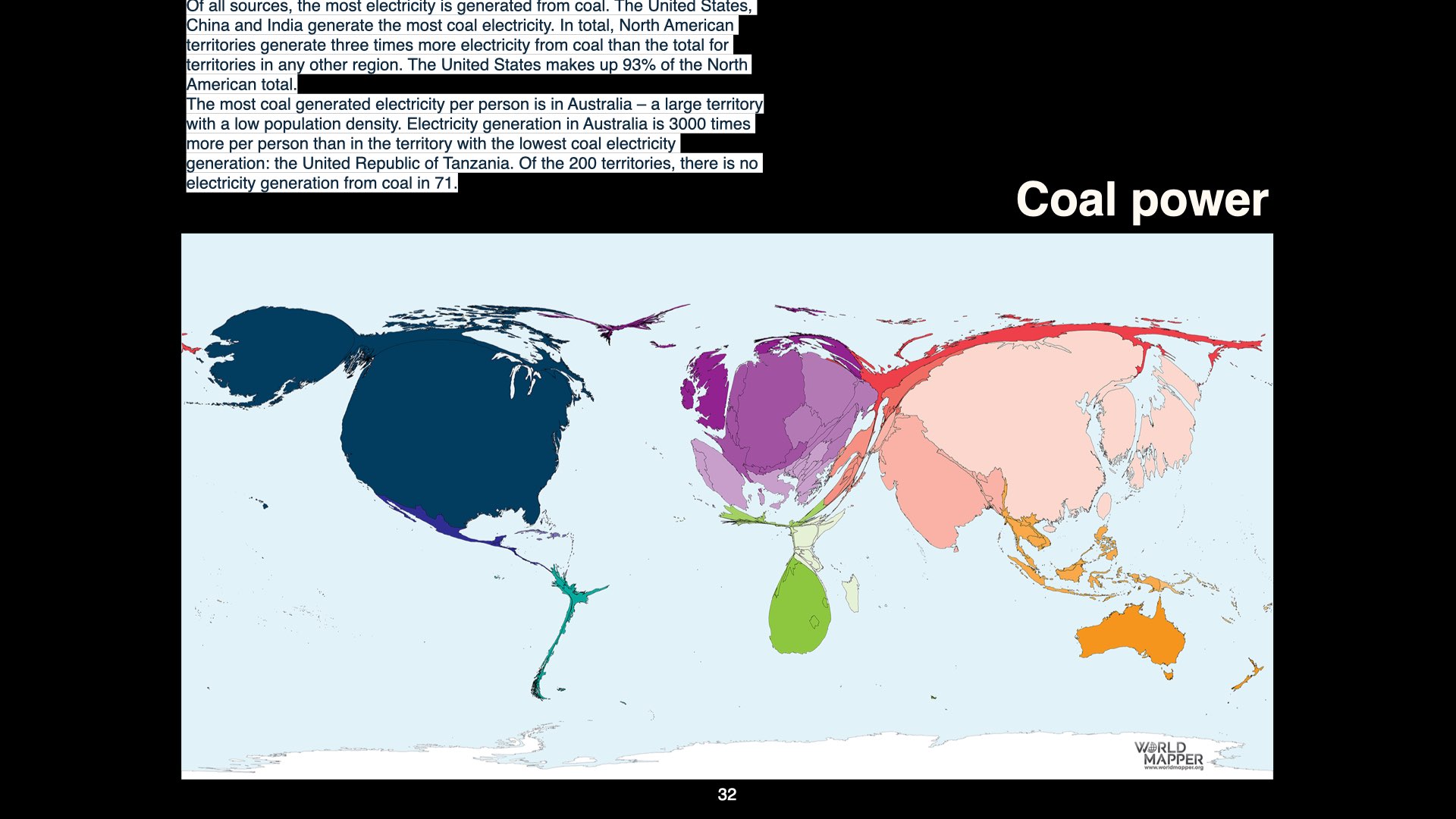

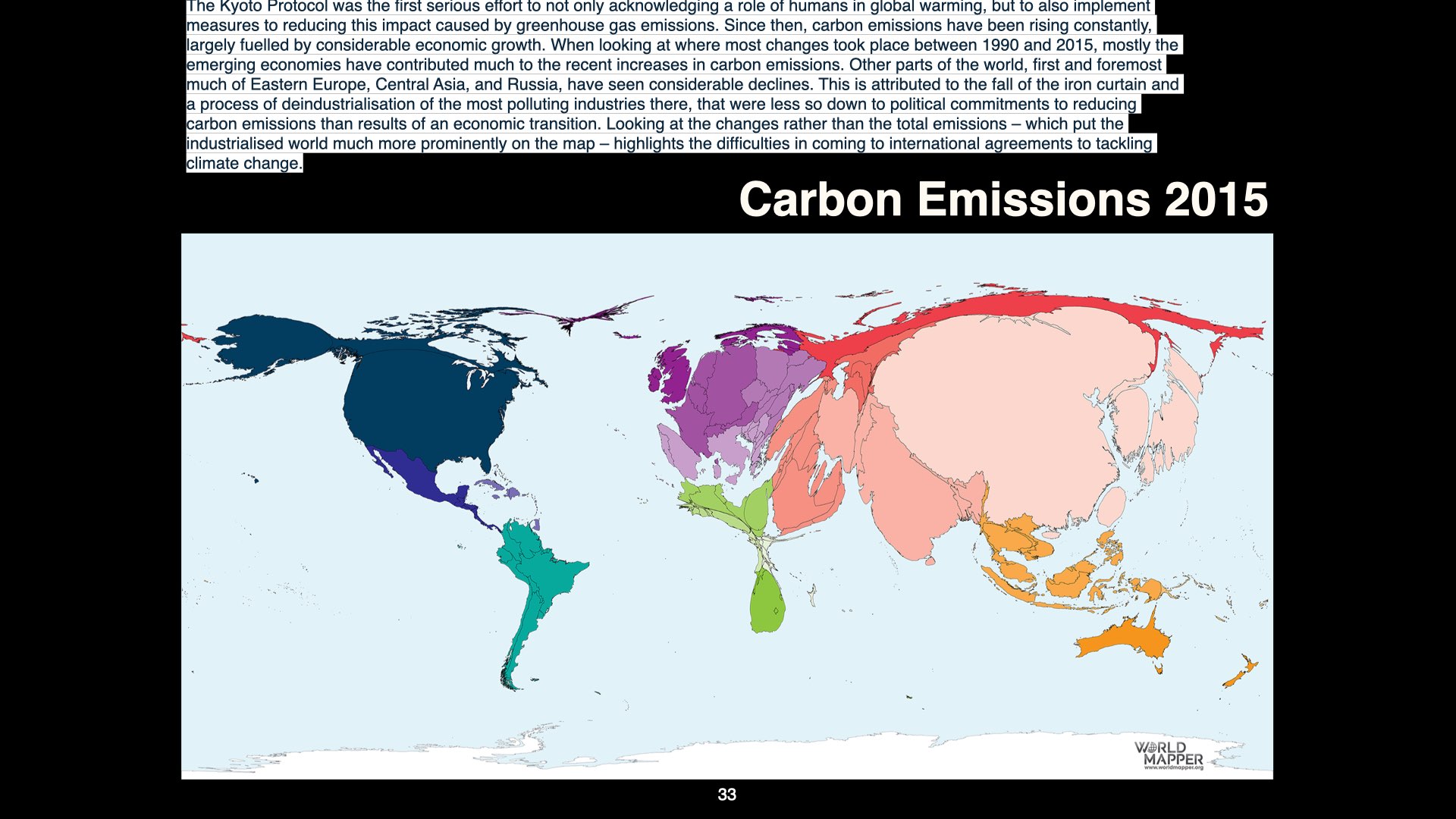

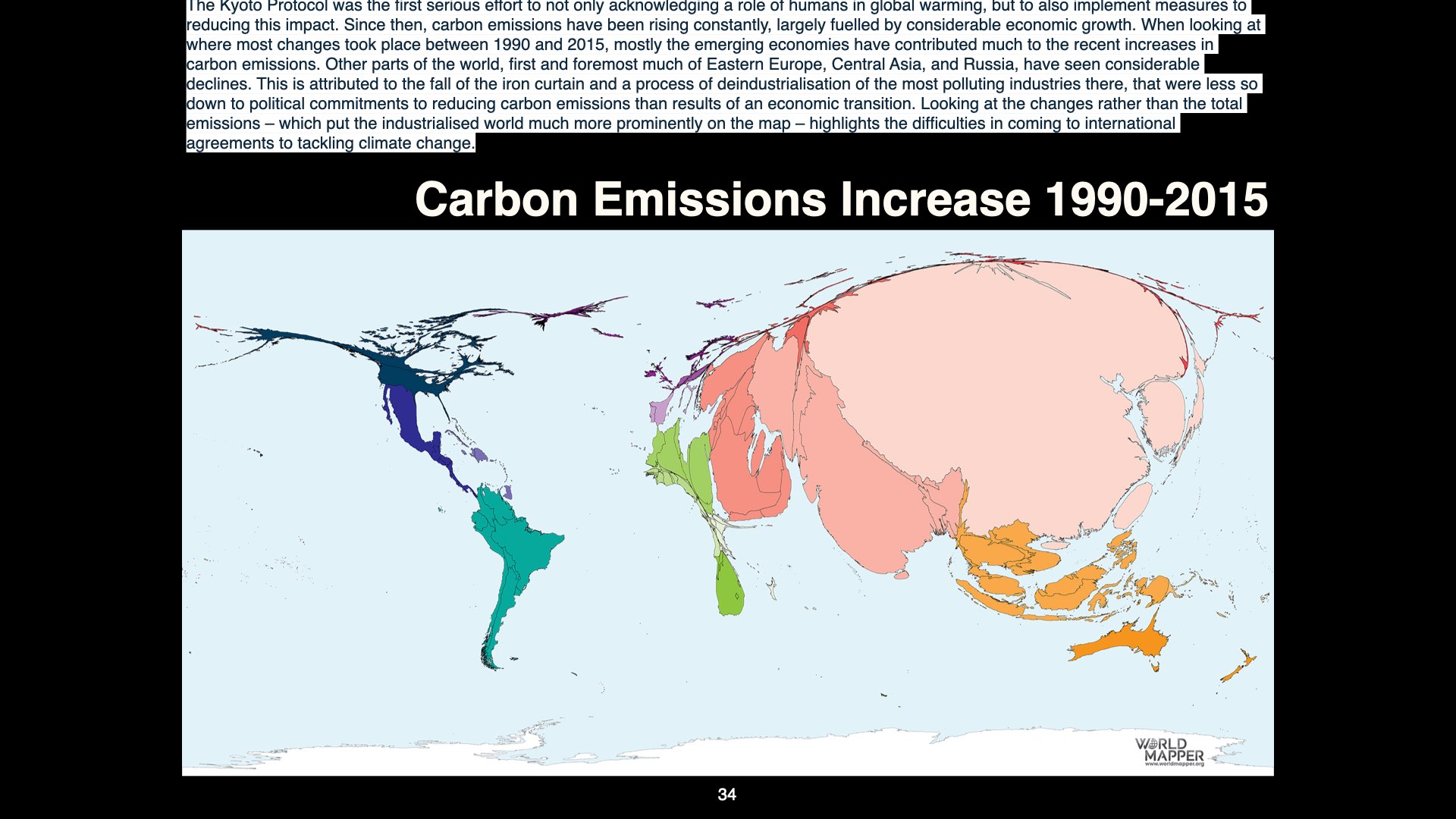

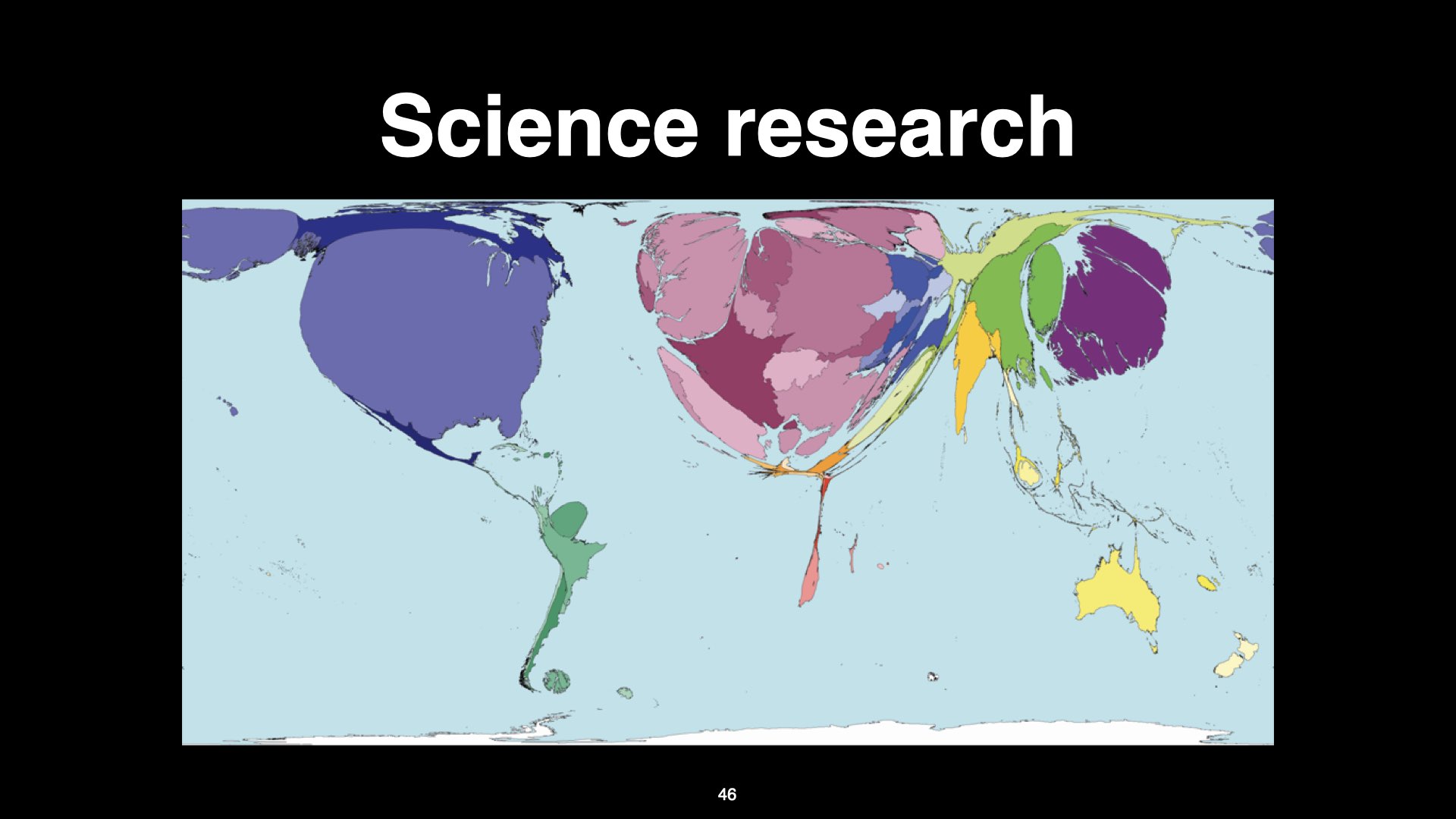

I want to show you some figures from a website called Worldmapper, which creates interesting images of world maps distorted according to the density of certain processes — for example, population density, education levels, or carbon emissions per capita.

If we look back 2,000 years ago, in year one (according to our calendar), most people were in Southeast Asia and Europe. Some distortion in South America is due to Inca and Maya populations, but mostly, the bulk of the population was in Asia and Northern Europe. Very few people were in North America, and New Zealand was unpopulated.

Moving forward 1,500 years, we see Asia and Northern Europe remain large, with Asia expanding. North America now grows in size, which shows that the population began to rise there. Later, during the last 500 years or so, Africa saw rapid population expansion.

This is very important, as continual population growth has a huge effect on biodiversity, both regionally and globally. Human impact is thus largely a consequence of very large numbers of people.

At the start of the previous century, in

Let us roll forward

Why has Africa’s population grown so rapidly? And can we explain this pattern?

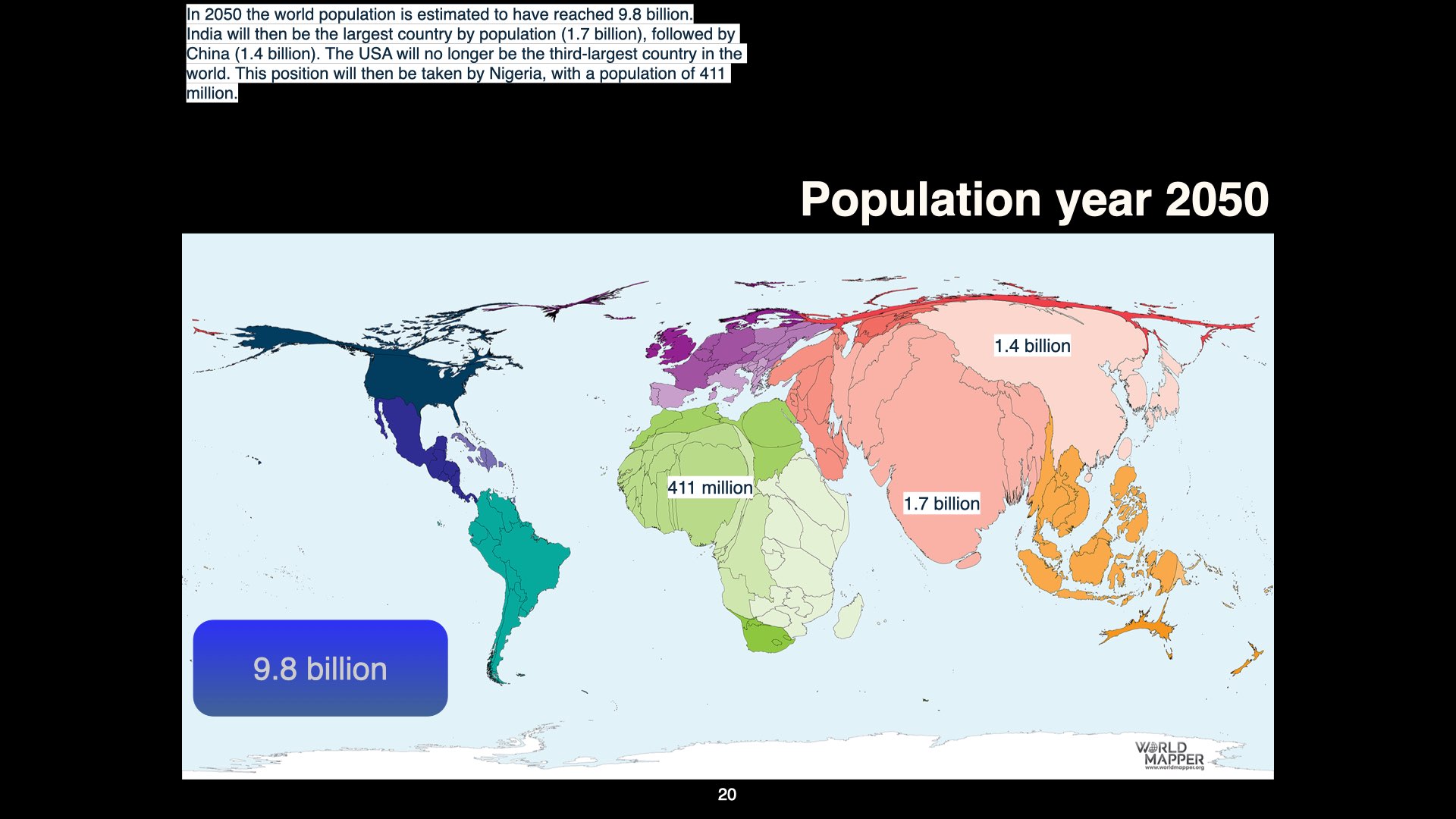

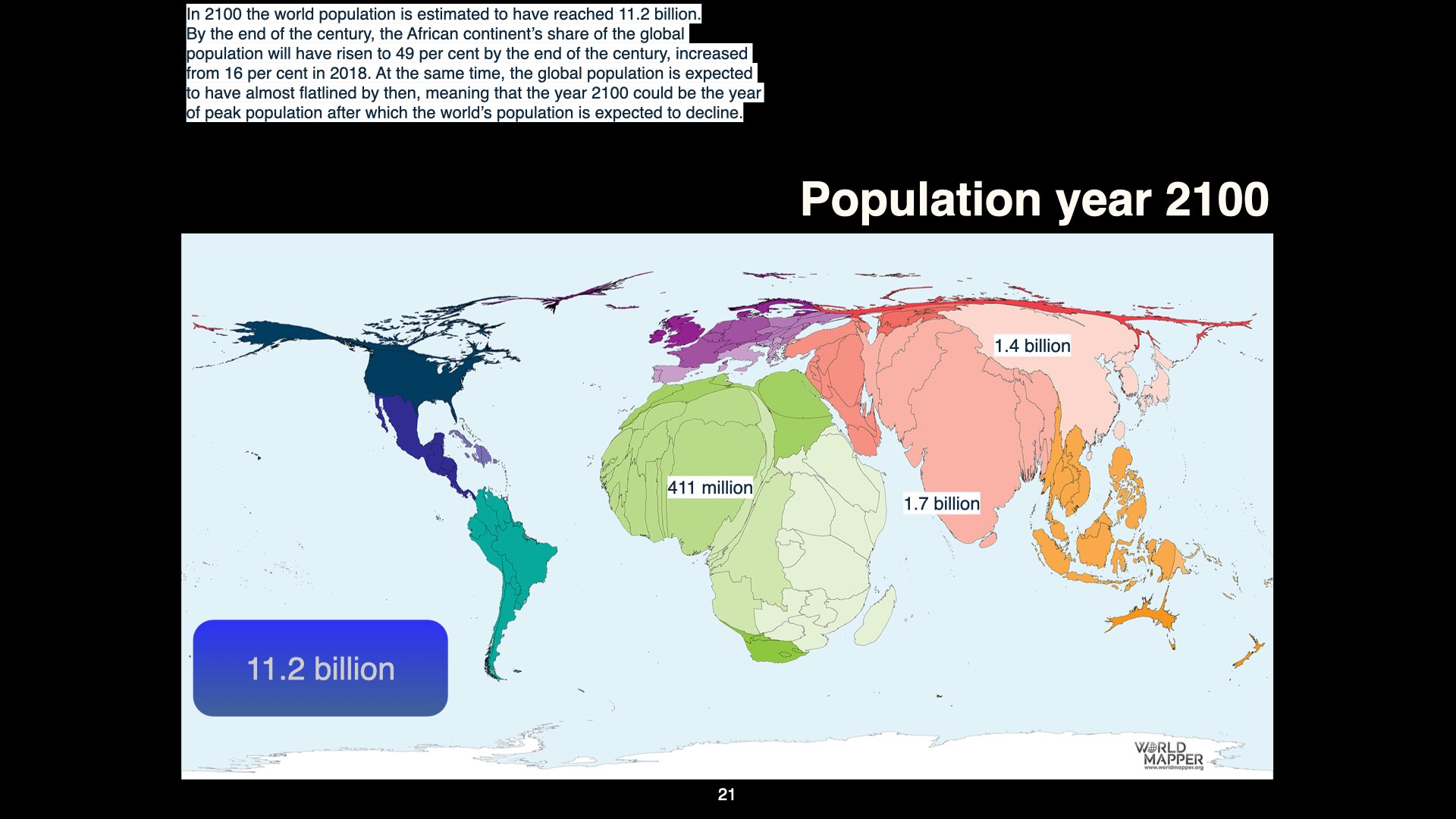

Extending to the year

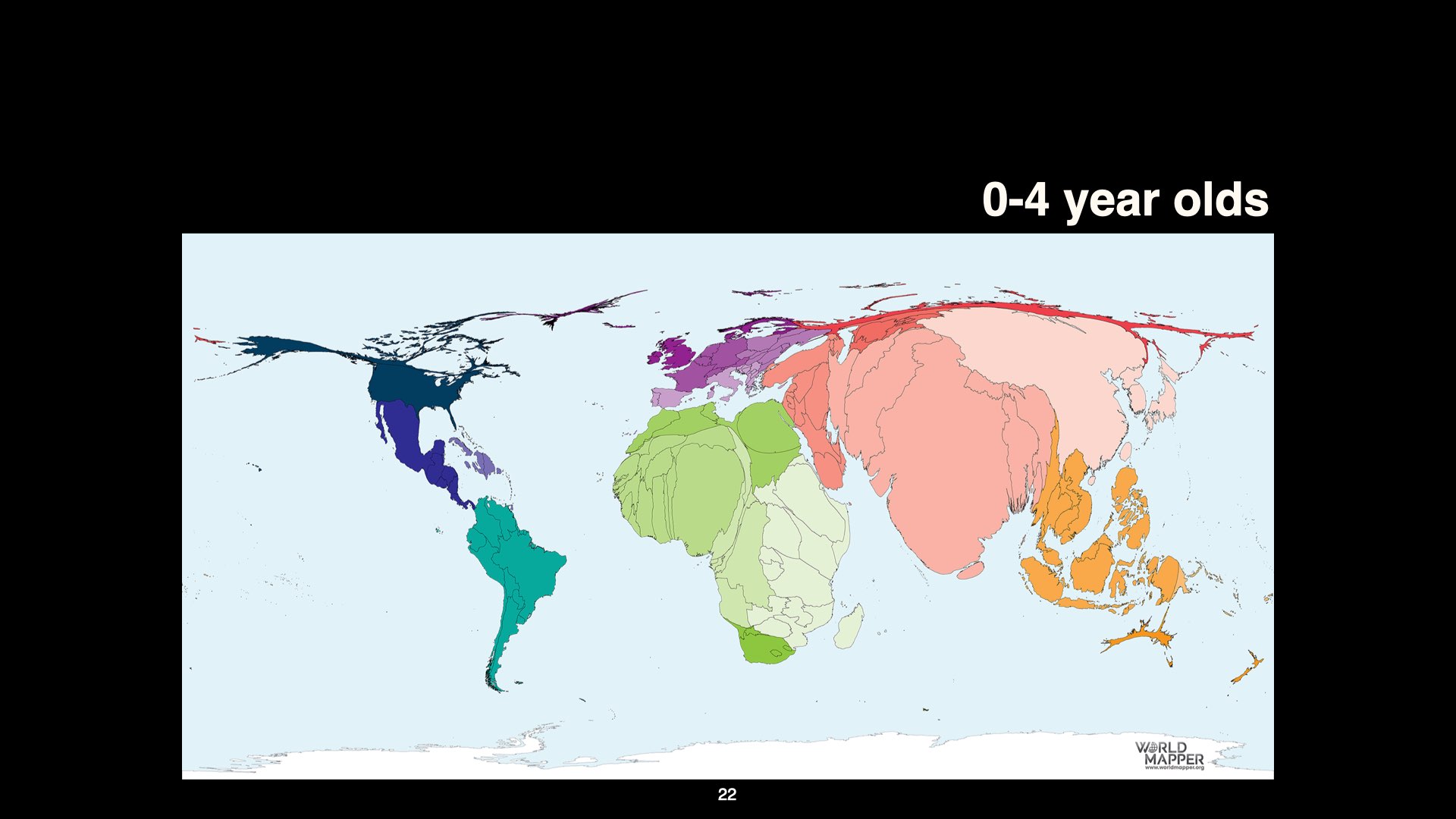

Examining demographics, Southeast Asia and Africa — regions experiencing rapid population growth — also have high proportions of very young people (aged

7 Patterns of Poverty, Urbanisation, and Education

In Africa and Southeast Asia, most people still live in rural areas; urban development has not proceeded at the same pace as in Europe or North America. South Africa is an exception, with more people making their lives in cities, a trend that continues to generate environmental challenges.

However, for much of Africa, people remain in rural settings. Industrial and urban development lags behind, and many areas remain undeveloped.

In Africa and Southeast Asia — the regions where population is growing most rapidly — the majority of people live in absolute poverty. The World Bank defines absolute poverty as income less than

Thus, the fastest-growing populations are also the poorest. This seems counterintuitive. If people are poor, why do they have more children?

8 Education and Gender Disparity

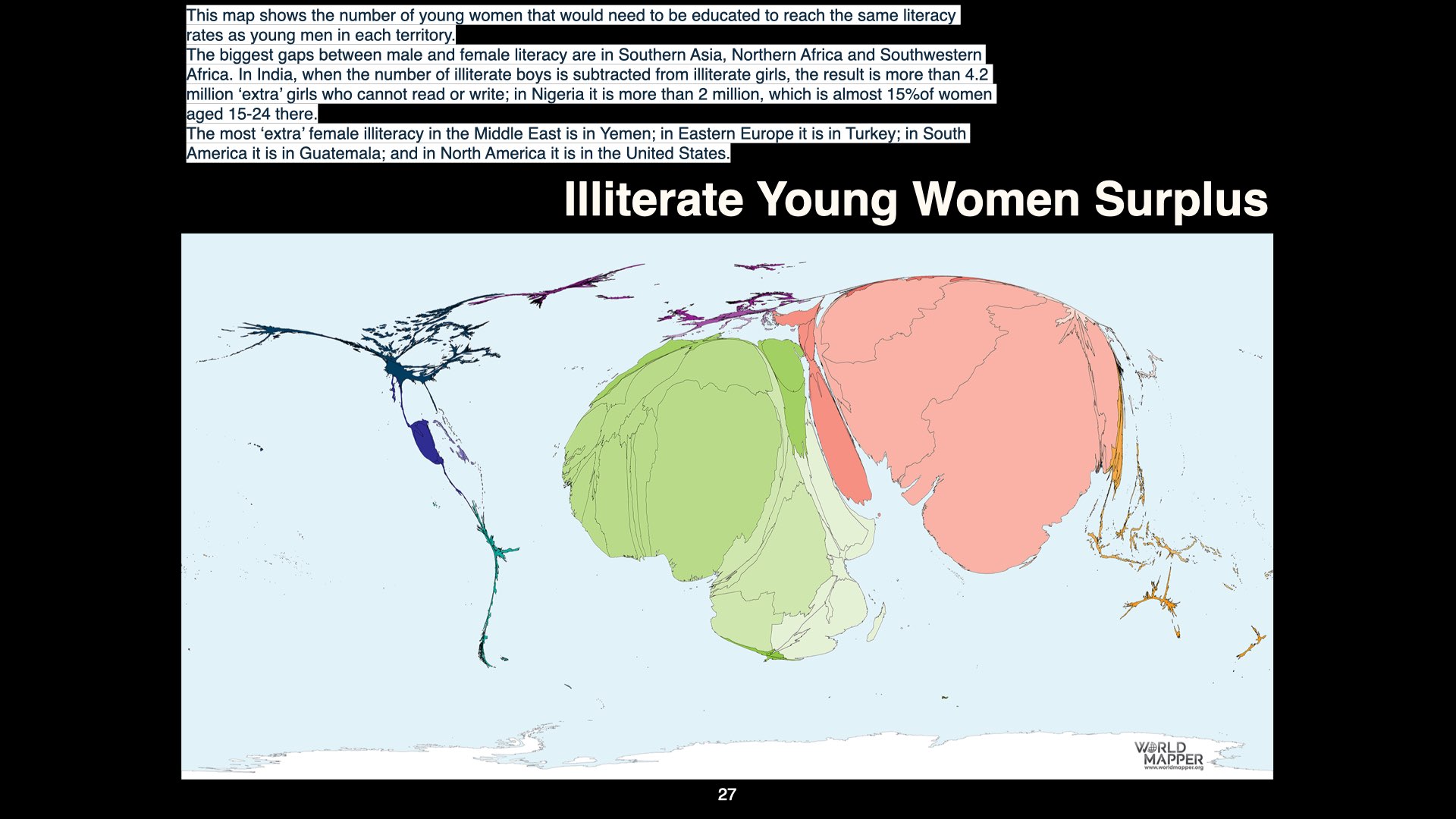

Another graph shows that the regions with high absolute poverty and high population growth also have the lowest education levels for women, compared to men. This is crucial — where women are uneducated, they tend to have more children. As education increases, women are empowered, and family size decreases.

But why is female education so much lower in these regions? This requires a deeper look.

9 The Role of Religion and Historical Structure

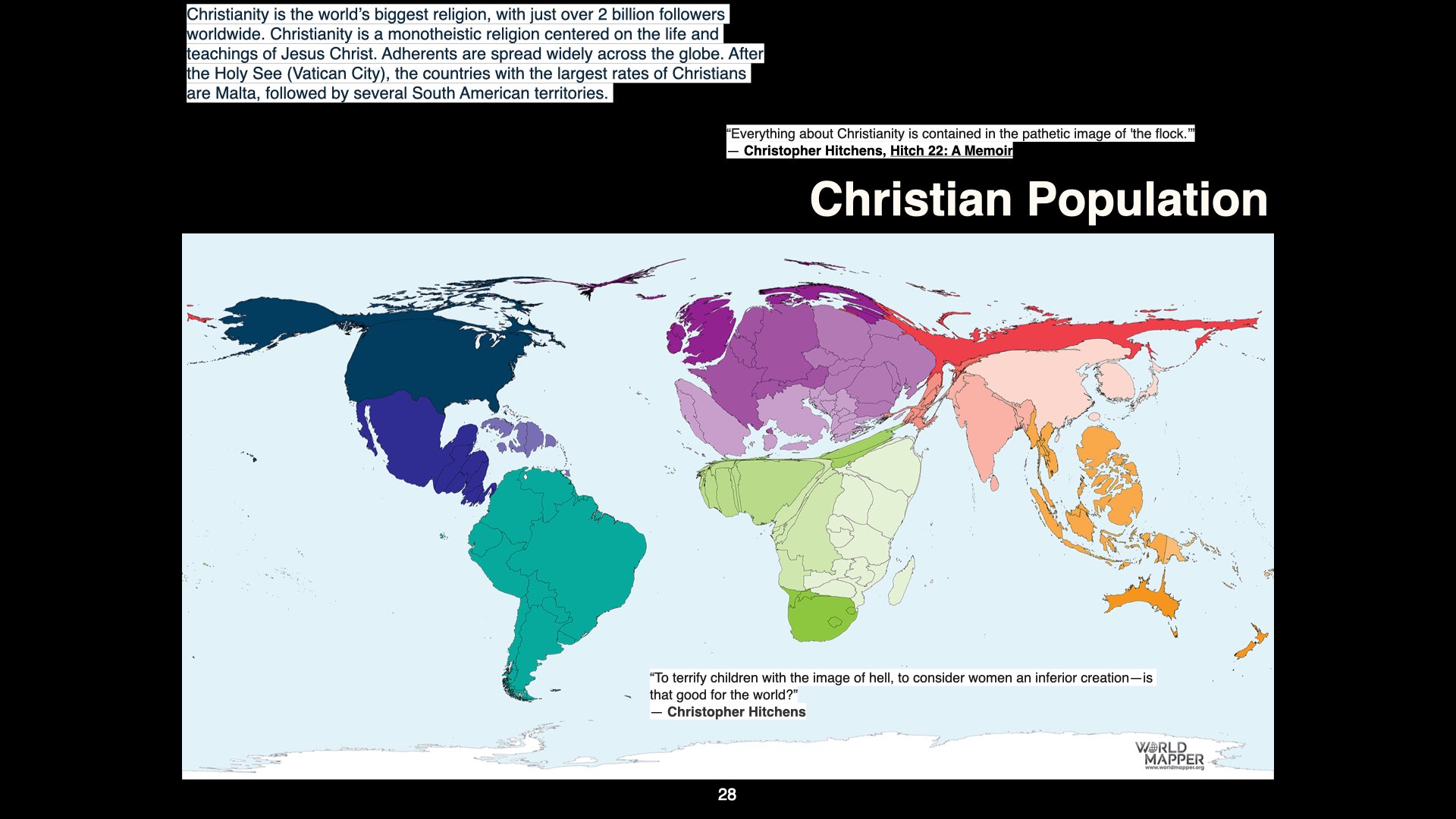

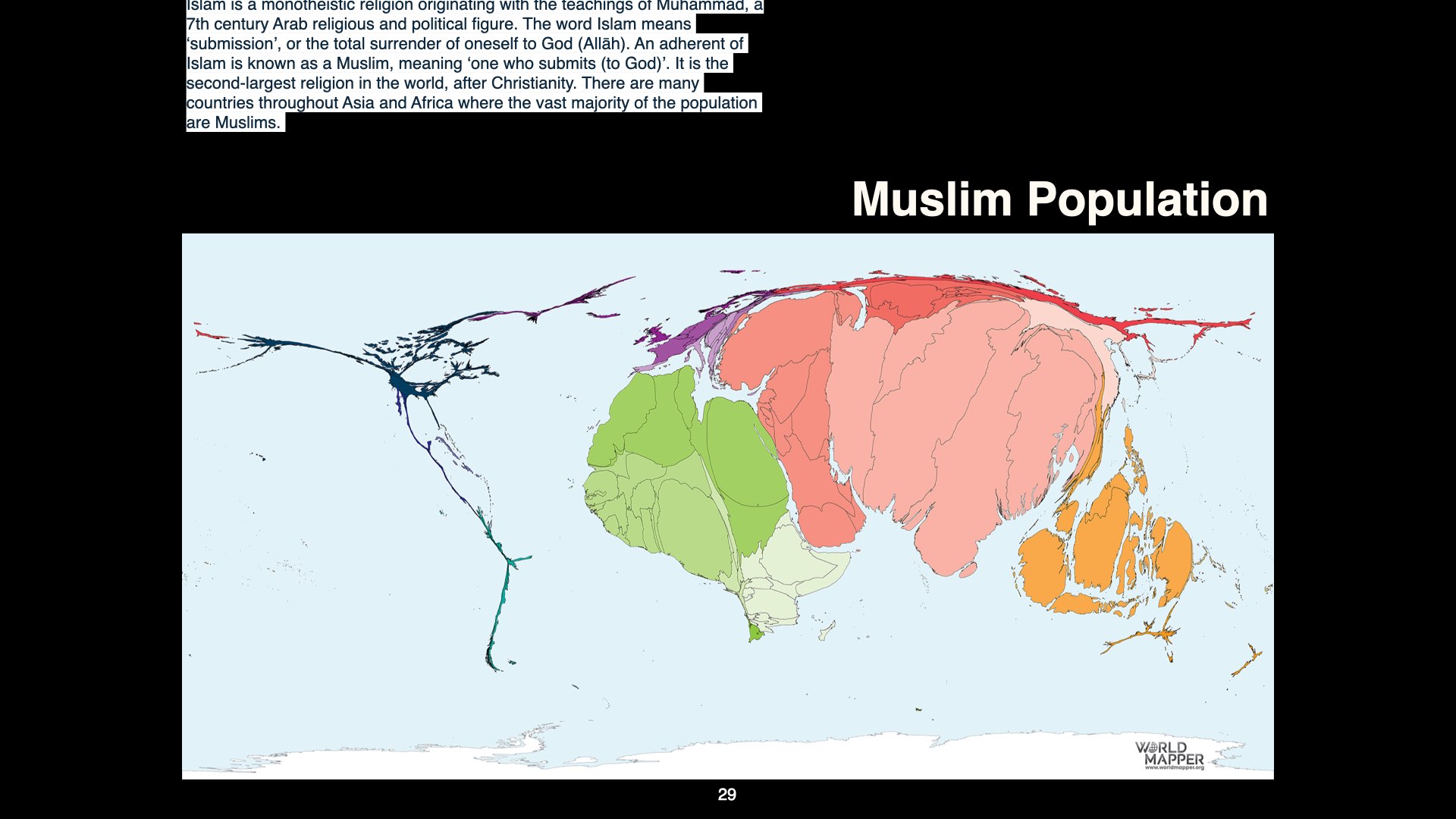

It is not the sole explanation, but religion plays a significant role. In large parts of Africa (particularly southern, sub-Saharan, and North Africa), Christianity is dominant, whilst in other areas, Islam has a major influence. Both Christianity and Islam, to varying degrees and in differing ways, have historically been associated with reduced access for women to education, sometimes through direct discouragement or outright prevention of female education. This disparity in education is, in my view, a central reason why population growth rates remain high in these regions.

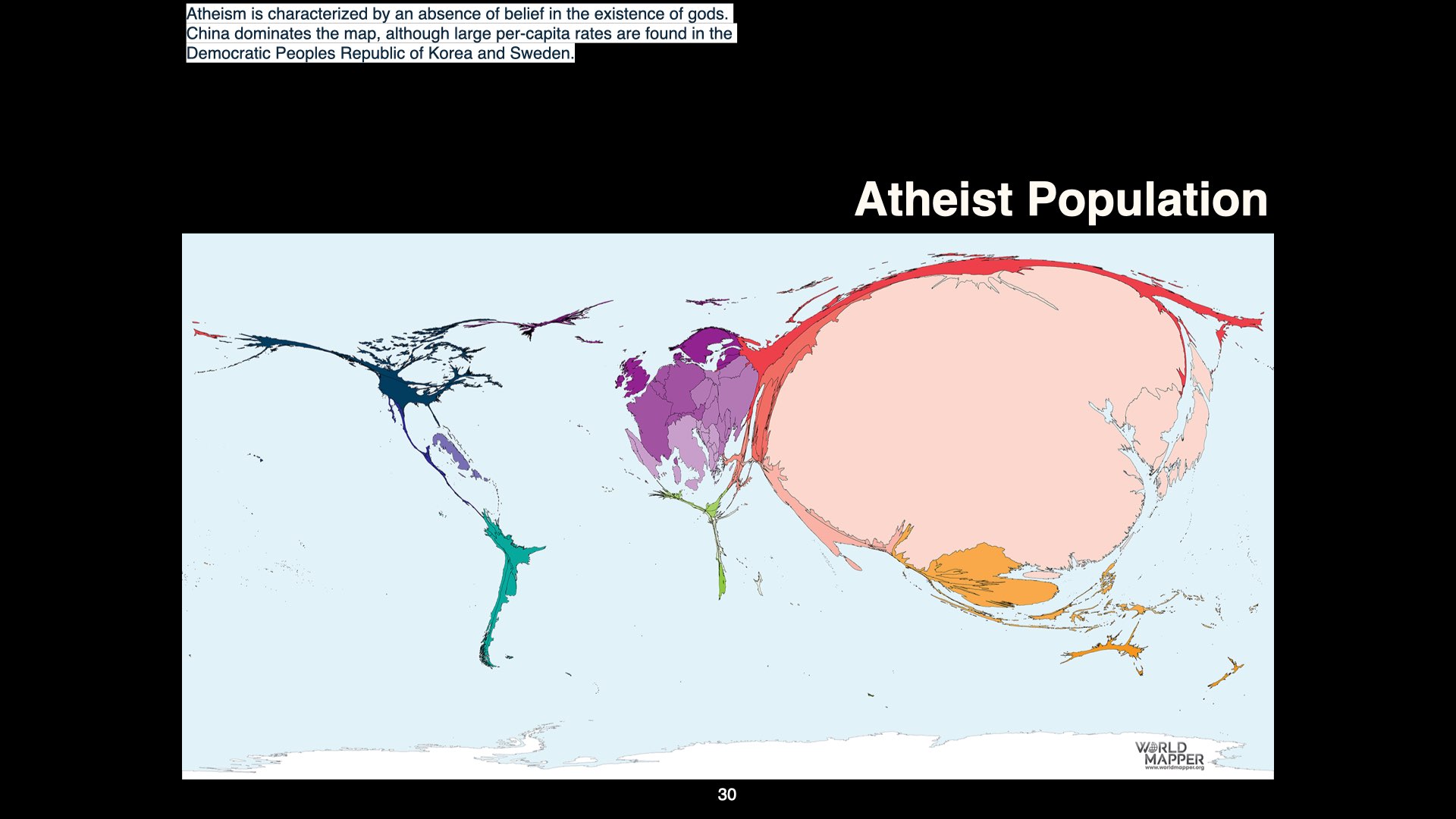

It is also interesting to look at regions in the world where religions are absent.

If you disagree or want to explore further, I encourage you to consult additional sources. As I always say, never take anything I say at face value — research and seek secondary sources.

Throughout history, many conflicts and ongoing strife in these regions have their roots in religious or cultural institutions, which more often than not have been sources of conflict rather than peace, prosperity, equality, or growth for all.

10 Human Impact and the Industrial Revolution

The reason for focusing so much on people is not to criticise religion, but to illustrate how having many people on the planet has created wide-ranging impacts on life on Earth. Whether we have too many people is a subject of much debate, and there is disagreement between people who make their argument on economic terms and those who make it on environmental terms.

Much of this began with the Industrial Revolution in North America and Europe, which led to the excessive combustion of fossil fuels. Coal, gas, and oil were consumed in vast quantities to grow the economies of these industrialised countries. This released excessive carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Since the 1900s, the developed nations in the Global North have contributed the most, per capita, to climate change.

South Africa, although developing, is the most industrialised country in Africa, and it ranks among the world’s top contributors to carbon emissions.

Countries that are now industrialising rapidly, such as those in Africa, North Africa, Saudi Arabia, the Middle East, China, Japan, and Southeast Asia, are increasing their carbon emissions at a faster rate than the Global North at present, as they attempt to close economic gaps.

11 Trends in Carbon Emissions and Renewable Energy

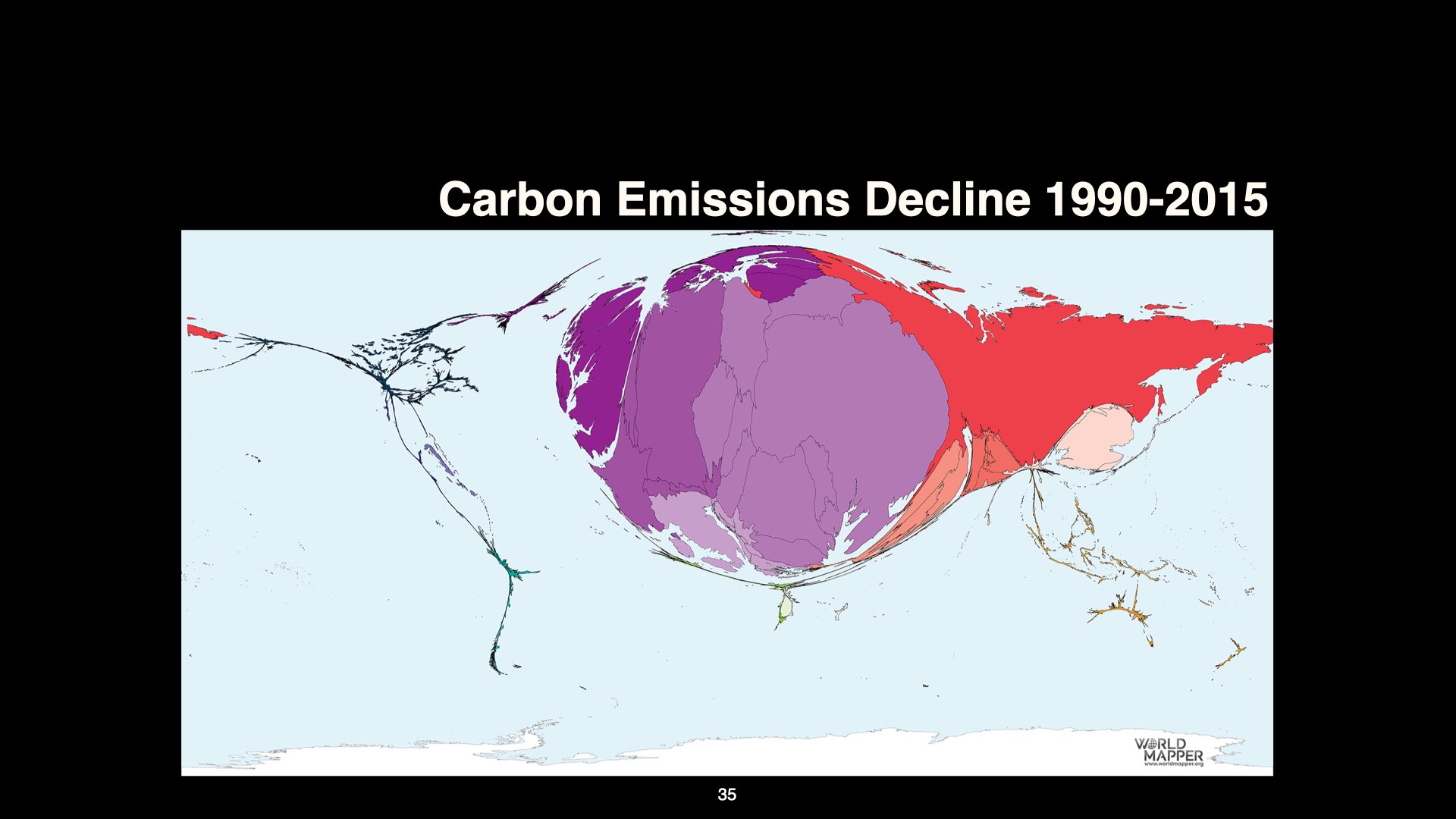

There has been a decline in Europe’s carbon emissions, particularly among Scandinavian countries, which have shifted much of their energy supply to renewables. The United States has not decreased emissions as much, for various political reasons, yet still shows a downward trend.

12 Healthcare and Environmental Disparities

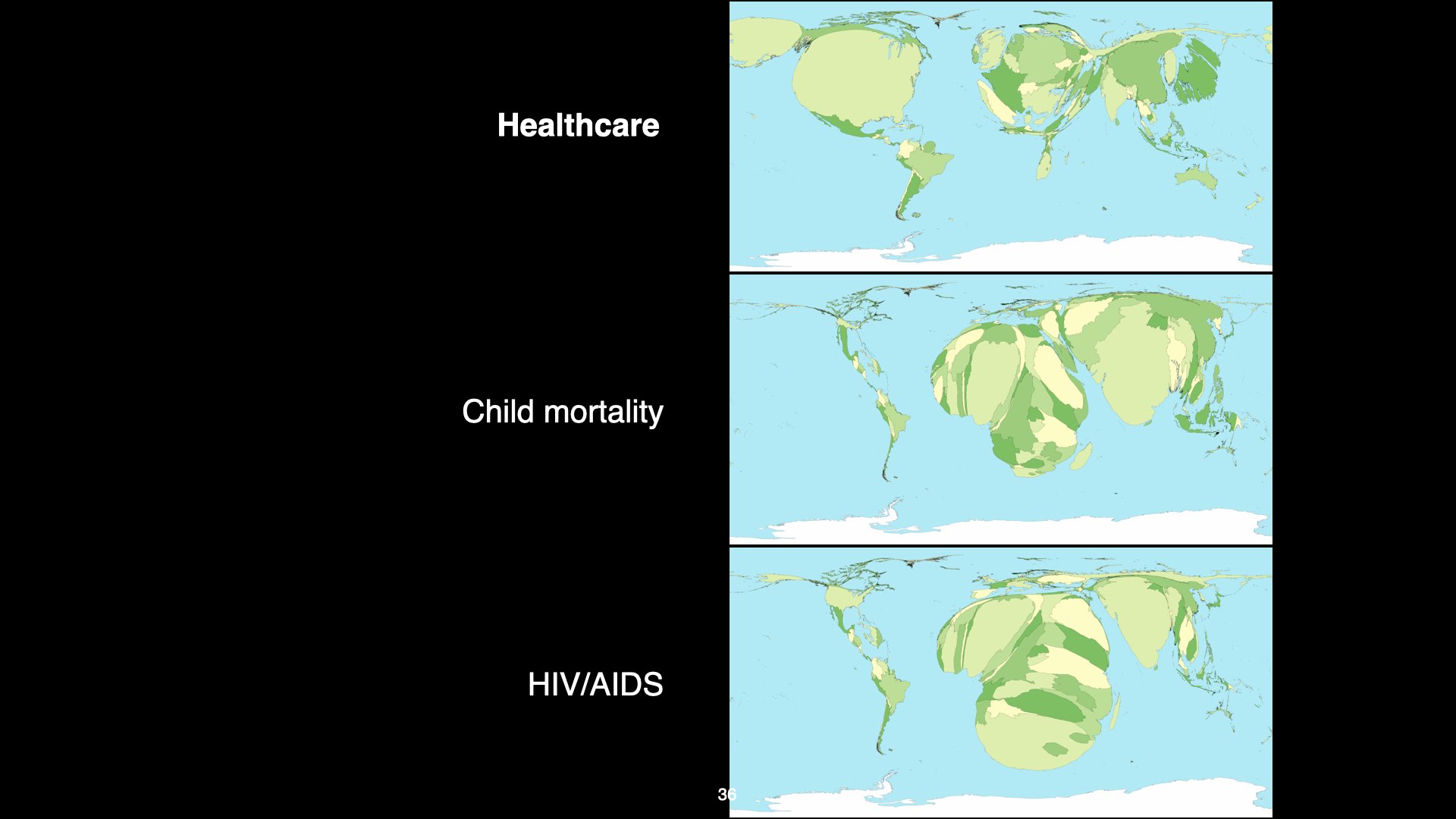

Poorer regions with the highest population growth have the lowest levels of healthcare, highest child mortality rates, and highest rates of HIV/AIDS.

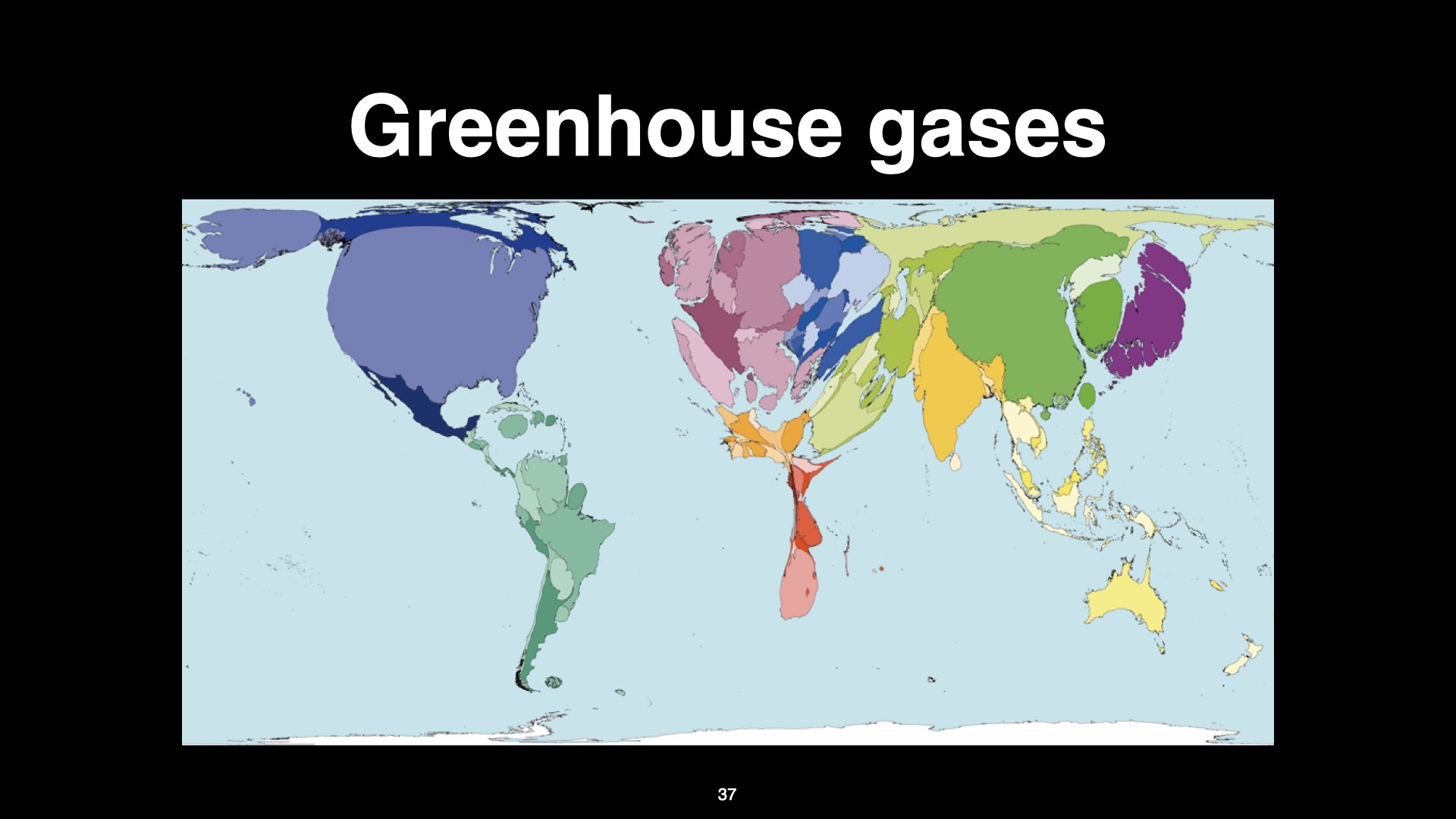

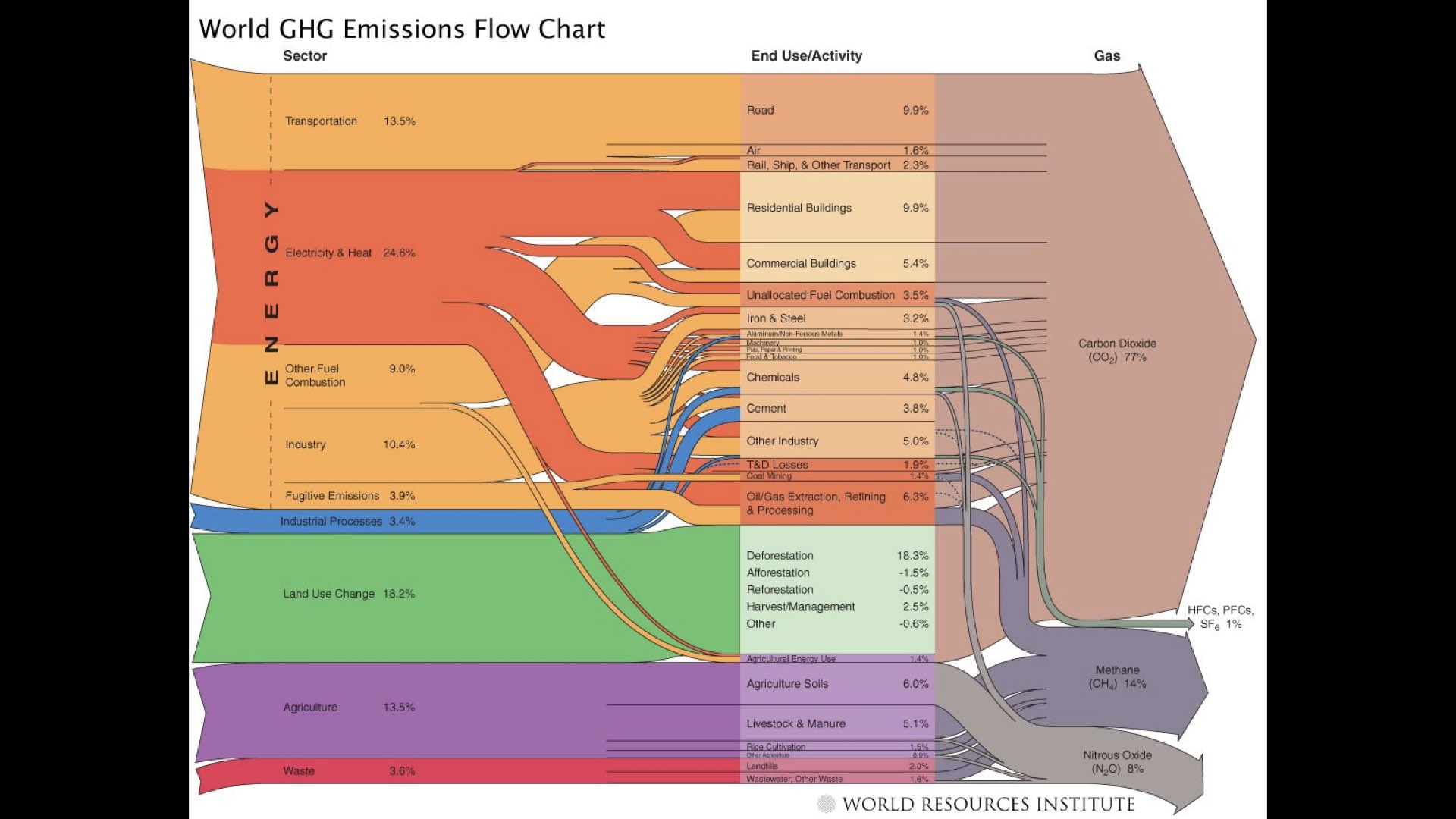

Greenhouse gas emissions remain highest in the most industrialised countries. Most carbon emissions originate from transportation, the generation of heat and electricity, industry, and other fuels. Land use changes — such as deforestation for agriculture, afforestation, reforestation, harvest management — can alter the flux of carbon dioxide.

Deforestation, in particular, leads to higher CO

In developing countries, rapid population growth has meant that agriculture has expanded, leading to increased emissions of methane and nitrous oxide, often exacerbated by changes in land use. Waste recycling infrastructure is generally lacking, and more pollutants flow directly into the environment.

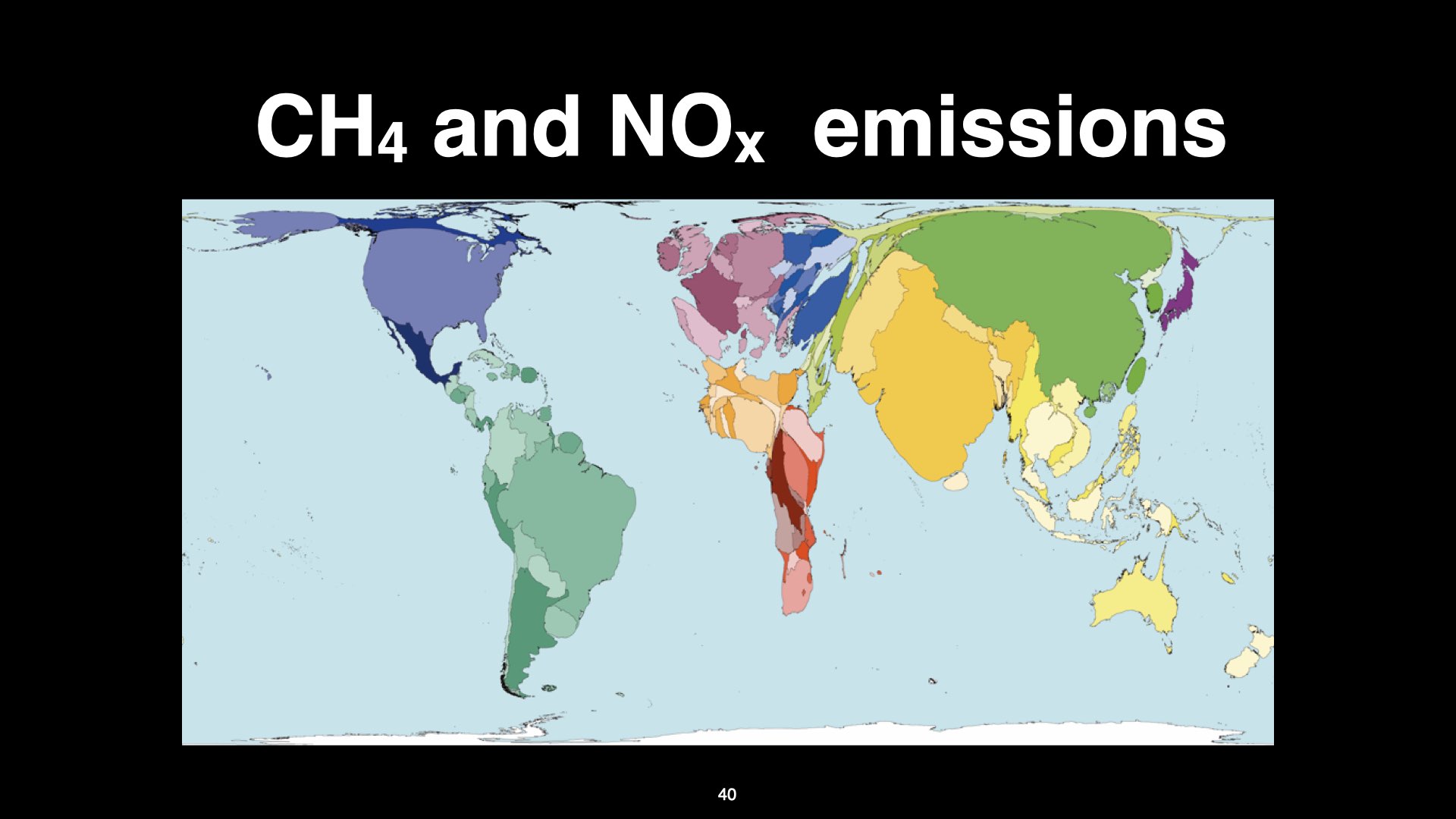

13 Methane and Nitrous Oxide: Regional Patterns

Looking at global patterns, Southeast Asia, South America, and China stand out for methane and nitrous oxide emissions. Livestock, mainly cattle, are the major methane source in South America. In Southeast Asia and China, the main sources are extensive rice farming (which under anaerobic conditions releases methane) and fertiliser use.

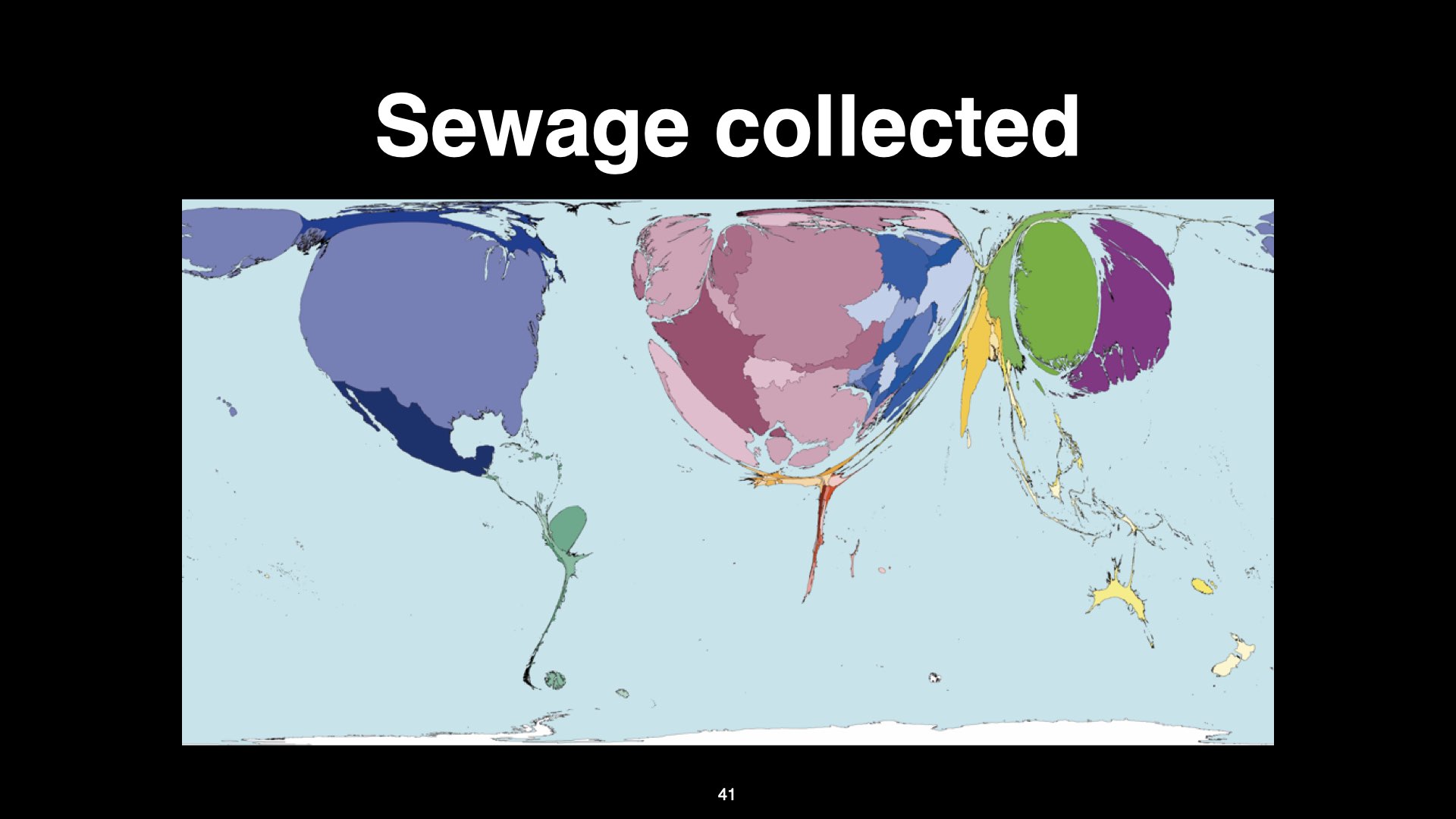

14 Waste Management and Pollution

In the developing world — Africa and South America — most sewage is not collected, but instead flows directly into the environment, aggravating pollution. In contrast, Europe and North America invest substantially in infrastructure to treat and recycle waste, reducing environmental pollution.

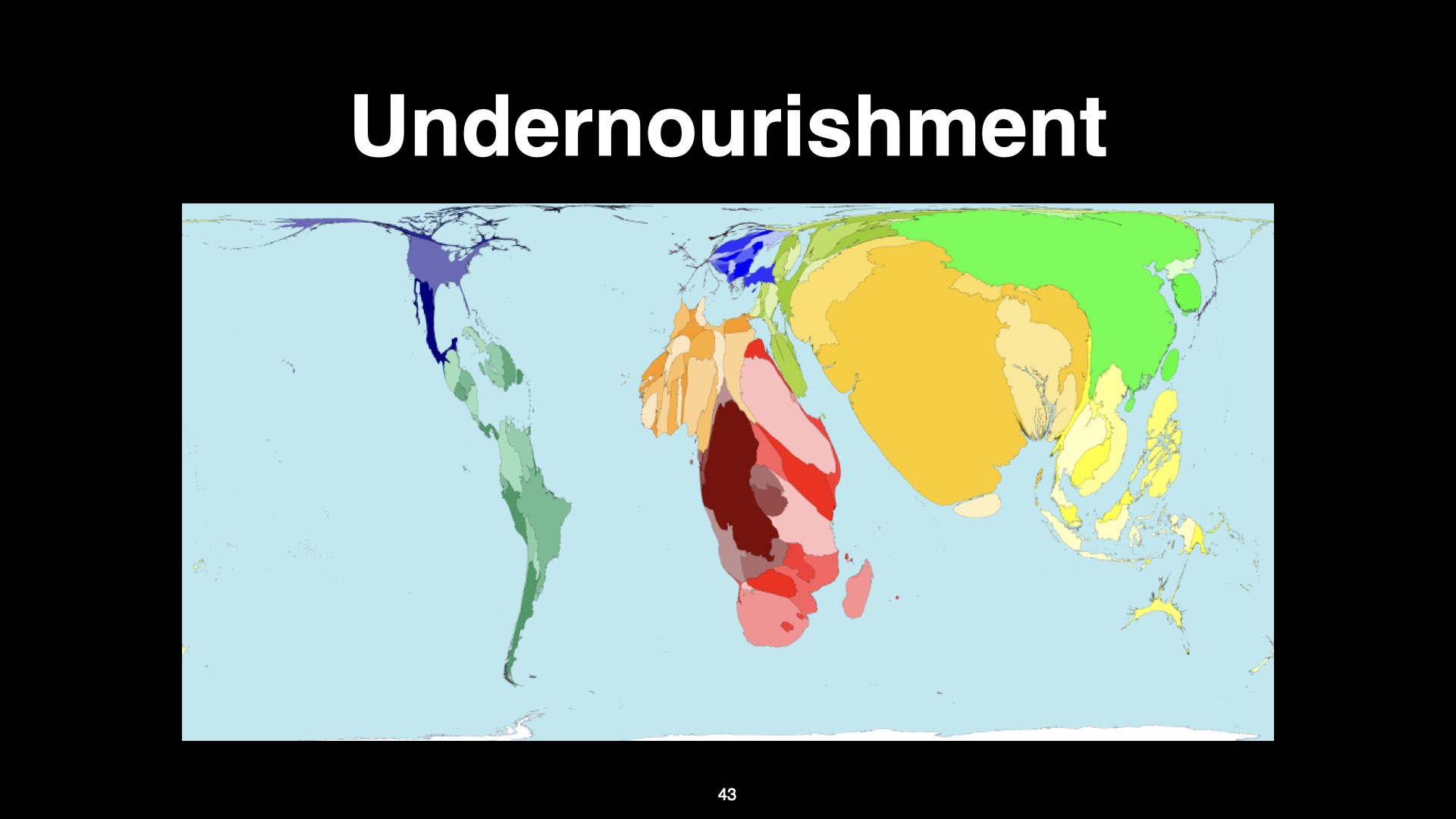

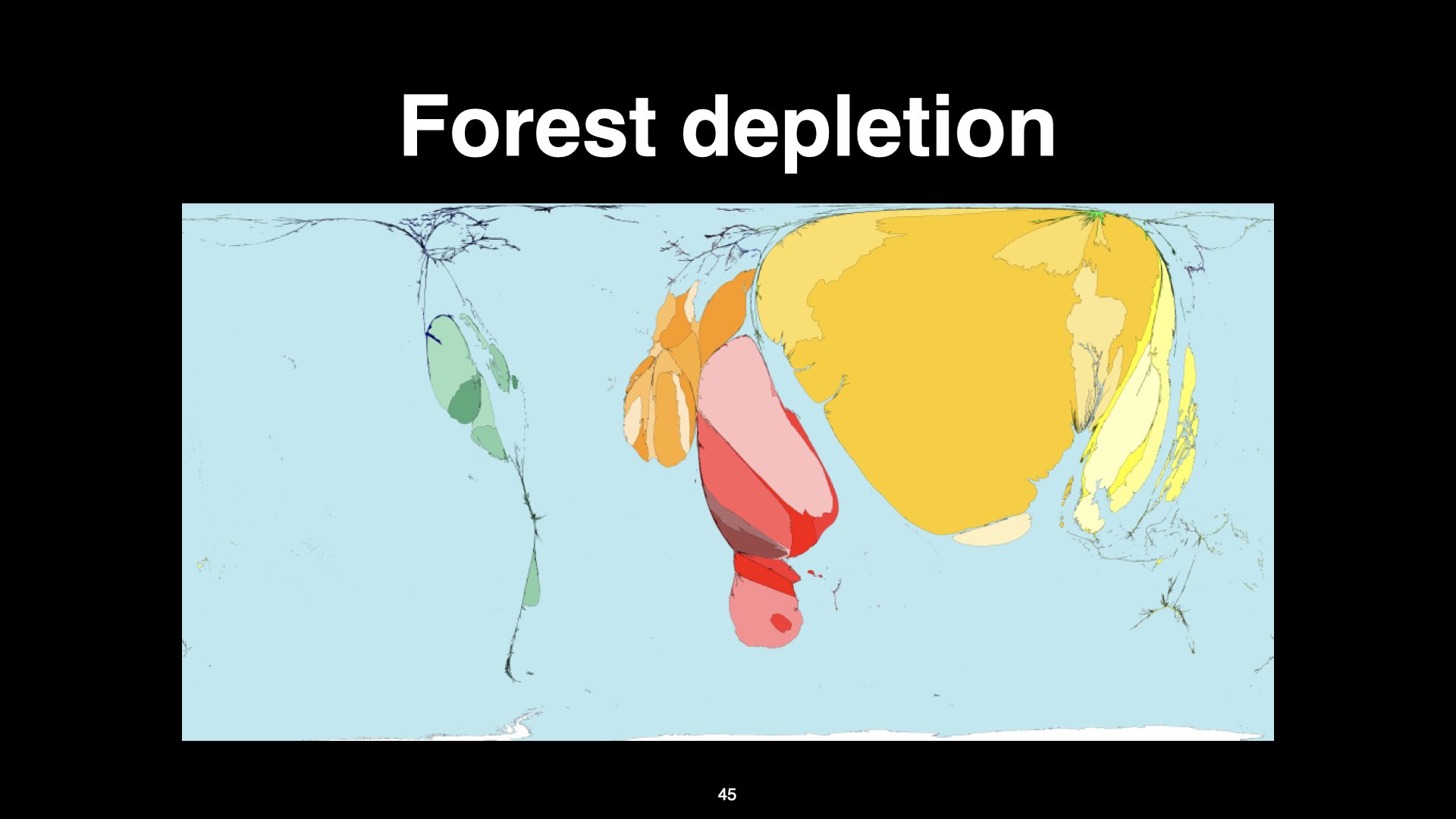

15 Undernourishment and Deforestation

Undernourishment is highest in regions with the fastest population growth, due to a lack of resources to support large families. Again, this links back to poverty and education.

Deforestation is occurring rapidly in Southeast Asia, China, South Africa, North Africa, Brazil, Colombia, Panama, and elsewhere. Forests are cleared primarily for agriculture, agro-industry, expanding residential areas and cities, and — particularly in Africa — to supply fuelwood for heating and cooking.

[Say something about fisheries exports.]

16 Science Research and GDP

Scientific research is most intense in countries with the highest gross domestic product (GDP). South Africa is almost unique on the continent for its scientific output, but remains far behind countries in the Global North.

17 Setting the Scene for the Module

To prepare for Thursday’s lecture, please read the paper “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity” by Johan Rockstrom and colleagues. I have posted the paper on iKamva; please have a look, as it discusses the boundaries that humanity must not exceed to maintain a habitable planet.

We have already described climate change in some detail, and its origins. The nitrogen and phosphorus cycles are also affected by waste management practices, and the safe limits for the nitrogen cycle have already been exceeded, moving us into dangerous territory there. We are also approaching a dangerous level of climate change, and the greatest ongoing threat to the planet is biodiversity loss, which itself is a direct result of too many people, lack of education, and the other factors I have described.

18 Looking Ahead

For the rest of the module, I will talk about climate change, ocean acidification, the nitrogen cycle, the phosphorus cycle, global freshwater use, and biodiversity loss. Each of these issues has major consequences for how stressed plants are within the environment, as human impacts on planetary boundaries indirectly produce the environmental stresses plants experience.

Thus, we will examine how plants perceive stress, the physiological and ecological effects of stress, and how plants cope with these challenges. That will be our focus for the rest of the module.

Reuse

Citation

@online{smit,_a._j.,

author = {Smit, A. J.,},

title = {Lecture 1: The {Limits} to {Life}},

url = {http://tangledbank.netlify.app/BDC223/L01-worldmapper.html},

langid = {en}

}