Lecture 2: Surface Area to Volume (SA:V) Ratio

- Surface Area to Volume Ratio, a universal law in biology.

- Understanding the plant (and algal) body plan.

- The major ‘functions’ of plants that are affected by SA:V ratio.

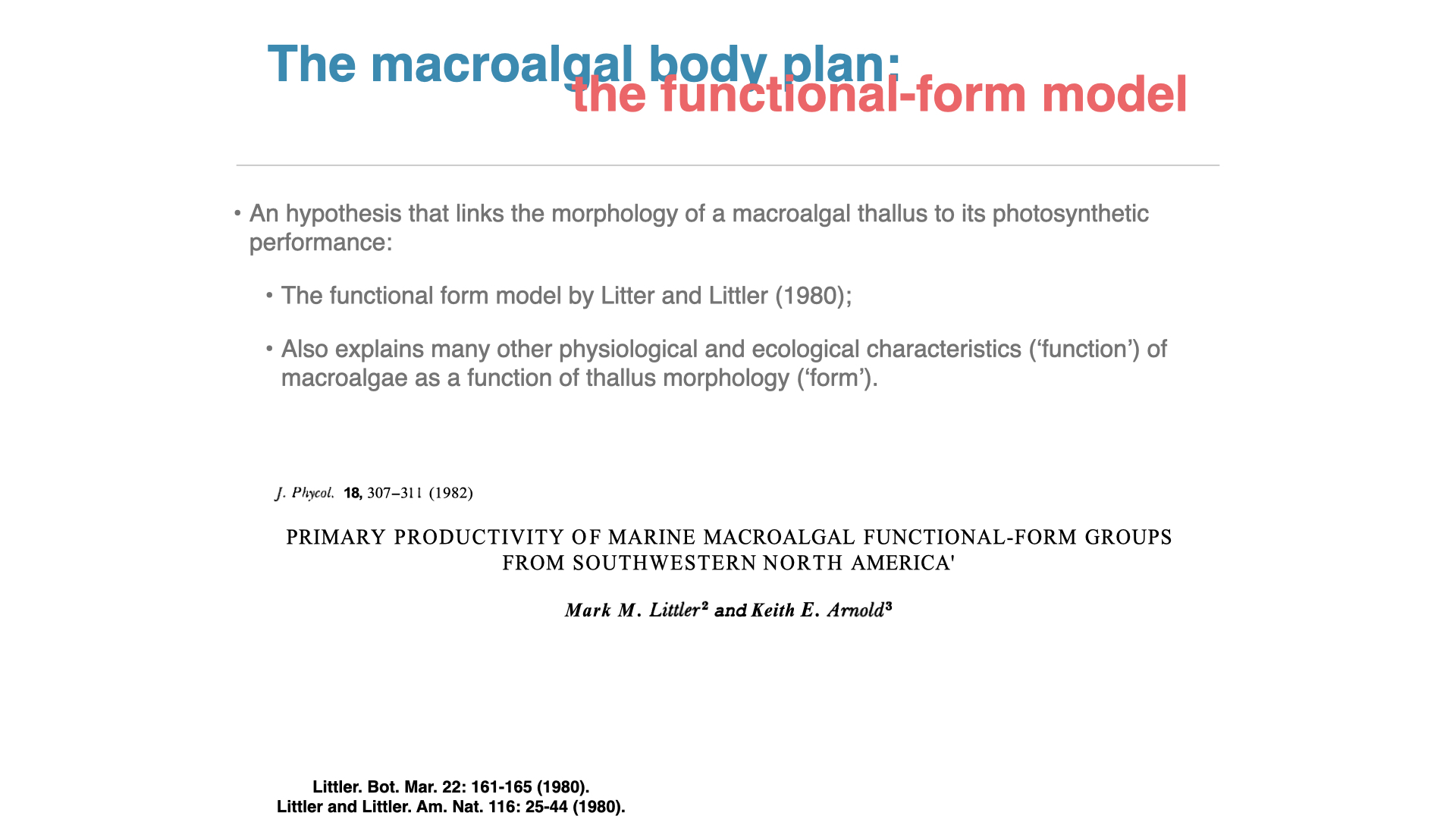

- Littler and Littler’s (1980) and Littler and Arnold’s (1982) functional form model (in seaweeds).

- Extending the functional form model to seagrasses (distribution, ecophysiology, and ecological interactions).

In this lecture, I will introduce students to the concept of the surface area to volume (SA:V) ratio as a fundamental biological principle that influences the structure and function of all living organisms. You will explore how this ratio affects the body plan and physiological processes of plants and algae, and how it shapes key functions such as nutrient absorption, gas exchange, and growth. We will delve into Littler and Littler’s (1980) and Littler and Arnold’s (1982) functional form model for seaweeds, which illustrates the ecological relevance of SA:V ratios in marine environments. Additionally, we will extend this model to seagrasses, and focus on their distribution, ecophysiology, and ecological interactions. The overarching goal is to equip you with the ability to connect this universal biological law to plant form and function in a variety of ecosystems.

By the end of this lecture, you will be able to:

- Define the “law” of SA:V in the context of plant biology and explain its ecophysiological implications.

- Recognise how SA:V affects plant processes such as photon capture, gas exchange, nutrient and water uptake, and thermal balance.

- Trace the broad evolutionary trajectory of plant body plans from high-SA:V unicells to low-SA:V, highly complex vascular plants.

- Explain why reductions in SA:V were often offset by innovations in transport systems, tissue specialisation, and reproductive strategies.

- Connect the concept of SA:V to both ecological function and evolutionary progression.

- Explain Littler and Littler’s (1980) and Littler and Arnold’s (1982) functional form model for seaweeds, identifying how the SA:V ratio plays a role in determining the ecological strategies of marine macroalgae.

- Extend the functional form model to seagrasses, analysing how their SA:V ratio influences their distribution, physiological adaptations, and ecological interactions in marine ecosystems.

- Apply the concept of SA:V ratios to broader ecological contexts, demonstrating an understanding of how this principle affects organismal form and function across terrestrial and marine environments.

1 Aims

In this lecture, you will encounter the general law of surface area to volume (SA:V) as it applies to plants. We will look not only at how this relationship governs ecophysiological processes — light capture, gas exchange, water relations, nutrient uptake — but also at how the historical unfolding of plant body plans across evolutionary time repeatedly involved shifts in SA:V. From single-celled ancestors in aquatic environments, to filamentous colonies, to the conquest of land and the rise of vascular complexity, the story of plants can be read as a history of managing this geometric constraint. By the time we arrive at gymnosperms and angiosperms, the reduction of SA:V is paired with new strategies — woodiness, vascular specialisation, seed protection — that allow plants to dominate terrestrial landscapes.

2 Introduction: the Universal Constraint of SA:V

When we speak of the “law” of surface area to volume ratio, we do not mean a legal statute but a geometric necessity. For any body, as size increases, volume grows faster than surface area. Thus, large organisms have proportionally less surface available relative to their bulk. For plants, this geometric law concerns almost every process: from light interception, diffusion of gases, uptake and loss of water, release of oxygen, to the excretion of metabolic byproducts.

The problem is obvious… the outer skin of a plant, or the thin leaf blade, is where exchanges with the environment happen; the inner tissues represent the metabolic demand. As SA:V declines, demand can outstrip exchange, unless the organism evolves compensatory structures and physiological strategies. The evolutionary history of plants, in many respects, is a series of solutions to this very problem.

So, when we talk about the surface area to volume ratio, we talk about the flat external surface — the skin, the total area of skin around a human body, or the two sides of a leaf, which is typically measured in square centimetres. The ratio of that quantity to the volume of something, which is the internal bulk of an organism — everything below your skin, or your meat, bones, and organs, or within, say, the leaf, where there might be one, two, or three layers of cells — is the volume, measured in cubic centimetres (or similar). So the ratio of these things — the surface area measured in square centimetres to the volume in cubic centimetres — is what is commonly called the surface area to volume ratio.

3 Ecophysiological Processes Affected by SA:V

Plants in their day-to-day lives require various things. They need to capture photons — they need to harvest light, in other words — so leaves provide a convenient two-dimensional flat surface, of which we can calculate the size, which translates directly to one of the units in the quantum measurement of light intensity, so metres squared. So the surface area of a leaf relates directly to the amount of area available for photon capture. It is quite easy to derive the total amount of photons falling onto a leaf surface if you know the total area in square centimetres of that leaf.

Plants must also acquire water and take up nutrients together with that water, and they must distribute all of these materials from the roots via the stems to the leaves. When they photosynthesise, one of the byproducts is oxygen. The oxygen must be released back into the atmosphere, and that is happening via the leaves again. So, the more surface area there is, the greater the area available for oxygen exchange. Similarly, the same holds true for carbon dioxide — the greater the surface area available within the leaf, the greater the amount of area exposed to the atmosphere by which carbon dioxide can be released back, or taken up from the atmosphere, into the leaves. There are various different metabolic wastes that need to be disposed of, which typically happens in the roots and so on.

All of these operations require — or are based on — various chemical, physical, and biological principles that impose various constraints on the rate at which these processes can operate. All of these functions are also constrained by the various parts of a plant body, the thallus. It also helps us to understand the construction — “construction” in inverted commas, because it has not been constructed by a person; it evolved. So we need to understand the various components that form the structure of a full plant body that permit these various different operations: CO₂ uptake, waste disposal, water uptake, and all of these.

Consider the leaf, the “elementary” structure that represents a high surface area relative to thin internal volume. Its planar geometry maximises light capture and gas exchange. However, this thinness comes at a cost: rapid desiccation, vulnerability to mechanical stress, and short lifespan. By contrast, succulent tissues (e.g., cacti) lower SA:V, storing water for long periods, but sacrificing the efficiency of gas exchange and photon interception.

Roots illustrate the same principle. Fine root hairs expand SA:V, enhancing contact with soil particles and nutrient uptake. Woody taproots, in contrast, reduce SA:V but add bulk for anchorage and deep-water access. Stems reveal the tension as well: thin ephemeral shoots exhibit high SA:V and rapid growth, while tree trunks embody low SA:V, gaining mechanical strength but relying on internal vascular conduits to transport water and nutrients to distant leaves.

These trade-offs (between high exchange capacity and long-term persistence) are seen everywhere in plant morphology.

4 An Evolutionary Trajectory of SA:V

4.1 From cells to thalli: the evolutionary expansion of form

The earliest photosynthetic organisms, cyanobacteria, appeared more than 3.5–3.8 billion years ago. These were single cells, with astronomically high SA:V: every molecule of cytoplasm lay within nanometres of the environment. Modern representatives—Anabaena, Nostoc—illustrate this stage. Exchange was so immediate that the notion of “transport tissues” was unnecessary.

By around 1.6–1.2 billion years ago, eukaryotic algae with chloroplasts were established. Simple unicells like Chlamydomonas still retained high SA:V. Filamentous forms such as Spirogyra (green algae) illustrate the next step: chains of cells with a high proportion of surface exposed. Sheets and blades (e.g. Ulva, “sea lettuce,” whose fossil relatives appear by the late Proterozoic) expanded surface even further.

But as the Proterozoic gave way to the Phanerozoic, multicellular algae acquired more corticated and branched thalli. Laminaria (kelps, later in the Cenozoic) or red algal corallines (Paleozoic onwards) show how thicker tissues reduced SA:V while providing toughness, buoyancy structures, and predator resistance.

4.2 Land colonisation and the reinvention of SA:V

The colonisation of land occurred by the Ordovician to early Silurian (~470–430 Ma). Early bryophyte-like plants (Marchantia, mosses) clung close to the ground with thin tissues of very high SA:V. Their solution was not to resist desiccation but to remain in persistently moist habitats, so they relied on films of water for reproduction and diffusion-based transport within their tiny bodies.

By the Devonian (~419–359 Ma), vascular plants arose. Their axes (Cooksonia, Rhynia) were small, but their bulk already reduced SA:V. The first evolutionary solution here was the invention of tracheids, which are specialised water-conducting cells that moved fluids internally, bypassing the limits of surface diffusion. With tracheids, plants could thicken their bodies and extend upward without each cell being forced to sit directly on the surface.

Lycophytes and early ferns pushed this further. Leaves (microphylls and later megaphylls) increased the photosynthetic surface despite declining whole-plant SA:V. Large Carboniferous lycophyte trees (Lepidodendron) relied on enormous root systems for water acquisition, while ferns like Psaronius deployed broad fronds (high-SA:V appendages) supplied by internal vascular bundles. The solution here was a division of labour such that the thin, expansive organs could intercept light and gases, while thicker stems and roots could provide support and transport.

Progymnosperms, including Archaeopteris (not to be confused with Archaeopteryx), have another solution… the evolution of secondary growth (wood). Wood lowered SA:V dramatically by packing immense volume beneath relatively little bark, but vascular cambium and growth rings allowed the stem to maintain supply lines to the distant canopy. This is the strategy that opened the door to true trees.

4.3 Gymnosperms and angiosperms

By the Late Carboniferous into the Permian (~310–250 Ma), the seed had arisen. As plants grew taller and bulkier, desiccation became a critical hazard. Gymnosperms solved this by evolving needle-like leaves — low-SA:V organs with thick cuticles and sunken stomata — that drastically reduced water loss. This was paired with resin canals and strong wood, allowing them to survive in dry, cold, or nutrient-poor environments. The loss of leaf area was offset by the efficiency of their vascular networks, which channelled resources through massive trunks.

Angiosperms, which show a rapid rate of diversification from the Early Cretaceous (~140–100 Ma) onwards, have the most flexible deployment of SA:V strategies. Some lineages retained high-SA:V ephemeral leaves for fast growth (grasses, annual herbs), while others adopted succulence, coriaceous leaves, or reduced laminae to cope with aridity. Importantly, angiosperms added hydraulic “solutions” such as vessels (wider, more efficient water-conducting cells than tracheids) that enabled rapid transport to support thin, high-SA:V leaves even in tall trees.

Reproduction also adapted. Seeds (in gymnosperms) and later flowers and fruits (in angiosperms) developed strategies to decouple reproductive success from body geometry. Spores required moist environments and high-SA:V gametophytes; seeds enclosed embryos with nutrient reserves, freeing plants from that constraint.

5 Plant Structures and Surface Area to Volume Relationships

When we talk about higher plants, these would typically be the things that we see outside the window. If you walk around in nature, these would be angiosperms and gymnosperms. All of them are comprised of roots, stems, and leaves.

The roots, of course, are the bits below the ground surface, which serves several purposes. From an ecophysiological point of view, the most important surface function is that it interacts with the soil, which is where the water is and where the nutrients are, which are taken up by the roots from the soils and transported up the stems to the leaves. Also, roots fulfil an anchorage purpose as well. You can imagine that things with a high surface area to volume ratio — adventitious roots with lots of fine root hairs — have more surface area in contact with the soil particles themselves. They become very effective at taking up water and nutrients from the soil and bringing it into the plant. So that is a function of a high surface area to volume ratio — the high surface area is associated with direct contact with the soil.

On the other hand, as surface area to volume ratio decreases, the amount of bulk increases. That you typically see under the soil surface as tap roots — deep roots that are quite important for anchoring large plants. They can penetrate quite deep into the soil — maybe towards the water table, far down where it can access water. Anchorage structures, root structures that have a low surface area to volume ratio but more bulk relative to the surface, are very good at anchorage, whereas as soon as roots branch out more, reducing the amount of bulk relative to surface area, you have more contact with the soil, and can access nutrients and water.

The stems, similarly — in very fine ephemeral plants, would have a high surface area to volume ratio. They tend to be flimsy, not very strongly constructed, but as soon as the trees become larger, taller in stature, the surface area to volume ratio of the trunk decreases. There is more volume relative to the external skin, the bark, and therefore it becomes far more strong in terms of its ability to sustain all the bulk above ground. So contrast very large, thick tree trunks to the very thin little stems of ephemeral plants — very different in terms of surface area and volume ratio, and also in terms of the structural strength of these various plant components.

Leaves, of course, are just flat surfaces, very strongly packed with chlorophyll a. Some leaves might become increasingly bulky, with more internal volume relative to the amount of surface area, and so they are able to store more water, becoming more adapted to drier climates. More ephemeral plants — things that have to grow a lot faster, like lettuces for instance — are very flimsy, and as soon as you leave them out in the sun, they wilt very quickly. That is a function of a high surface area to volume ratio. Things like a cactus, for instance, have a huge amount of bulk; you leave it in the sun, and it sits there, fine, for weeks and months. That is because there is very little surface area relative to the amount of bulk through which water loss can take place.

So, it is quite easy to understand how the surface area to volume ratio constraint imposes various different adaptive or evolutionary benefits to plants to survive under certain conditions and environments. It is very easy to see when you walk around in nature, moving from forested areas at high latitudes to the tropics at low latitudes — the plants become very different in appearance and form, going from wet mesic areas to dry environments, to desert kinds of environments. The reason they look different is because there are major changes in the ratio of surface area relative to the volume of these plants.

6 Surface Area to Volume Ratio in Seaweeds (Macroalgae)

Plant structure concepts can also be translated to seaweeds — algae that live in the ocean or in freshwater. They have similar structures, though called something else. In seaweeds, you typically have no roots but a holdfast, which is just like a hand — sometimes called a hapteron (plural haptera) — and looks like a hand that grabs onto something for anchorage. The only purpose of a hapteron is to anchor a seaweed onto the ground, and larger seaweeds have larger haptera in order to grab onto more surface area and more rock, so that they can anchor better, especially in wavy environments.

There is also a stipe, which is equivalent in terrestrial plants to the stem, but in seaweeds is called the stipe. Then there are the fronds, which are equivalent in function to the leaves in higher plants. We see various surface area to volume ratio variations across seaweed types, as outlined in one of the papers you are meant to read.

Together, the holdfast, the stipes and the fronds are called the thallus (plural thalli).

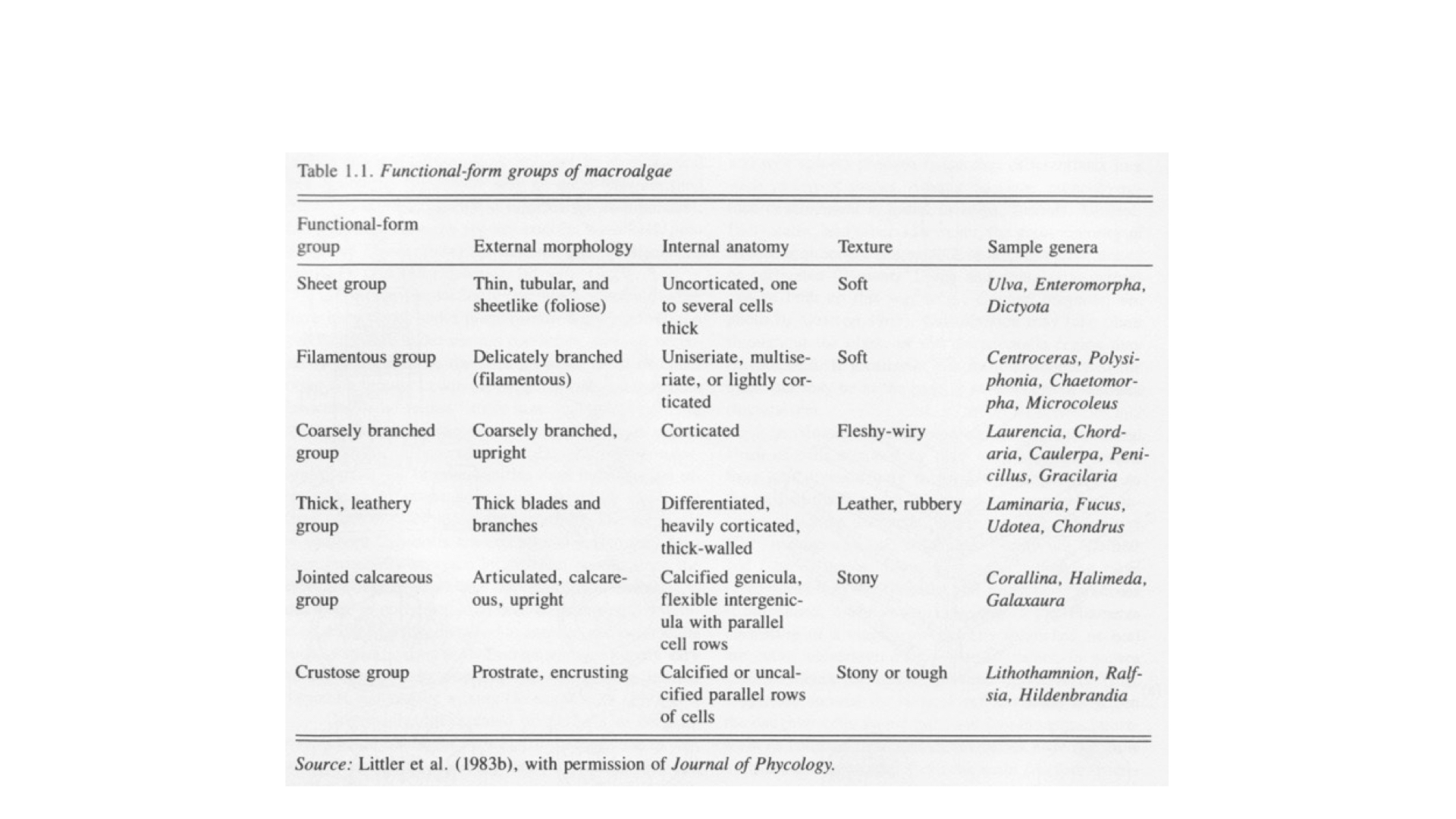

6.1 Littler et al.: functional form groups in macroalgae

This is the important paper that you need to read. It was published originally in the late 1970s by Mark and Diane Littler, but the one I want you to read for this lecture is on eConver — go and download it. It is called “Primary Productivity of Marine Macroalgae or Marine Macroalgal Functional Form Groups from Southwestern North America.” What Mark and Diane Littler did, and Keith Arnold in later collaborations, was to look at functional forms of seaweeds, dividing them into different groups, each characterised by different surface area to volume ratios. The experiments clearly show that as surface area and volume ratio changes, various ecophysiological functions of the algae change.

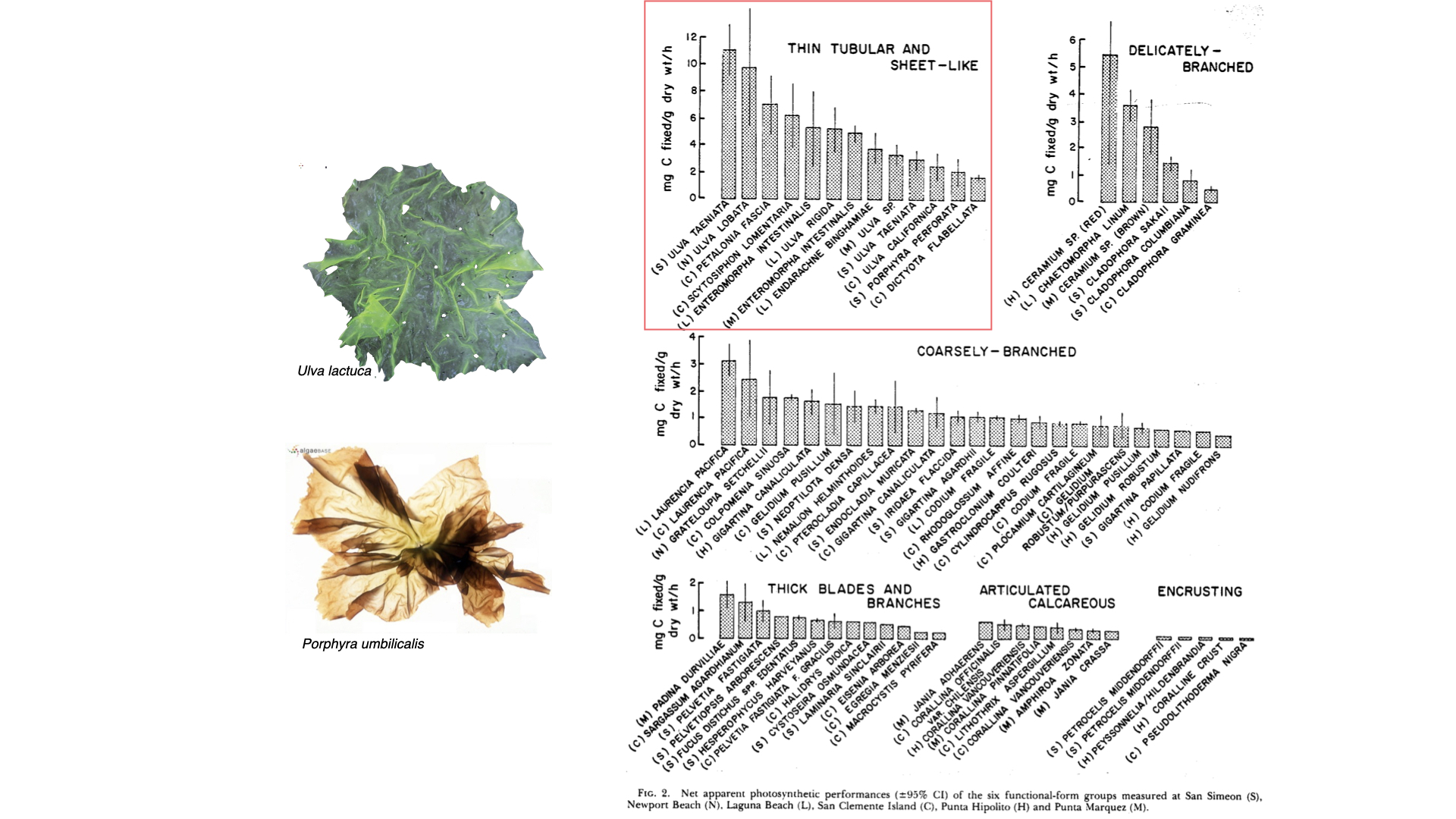

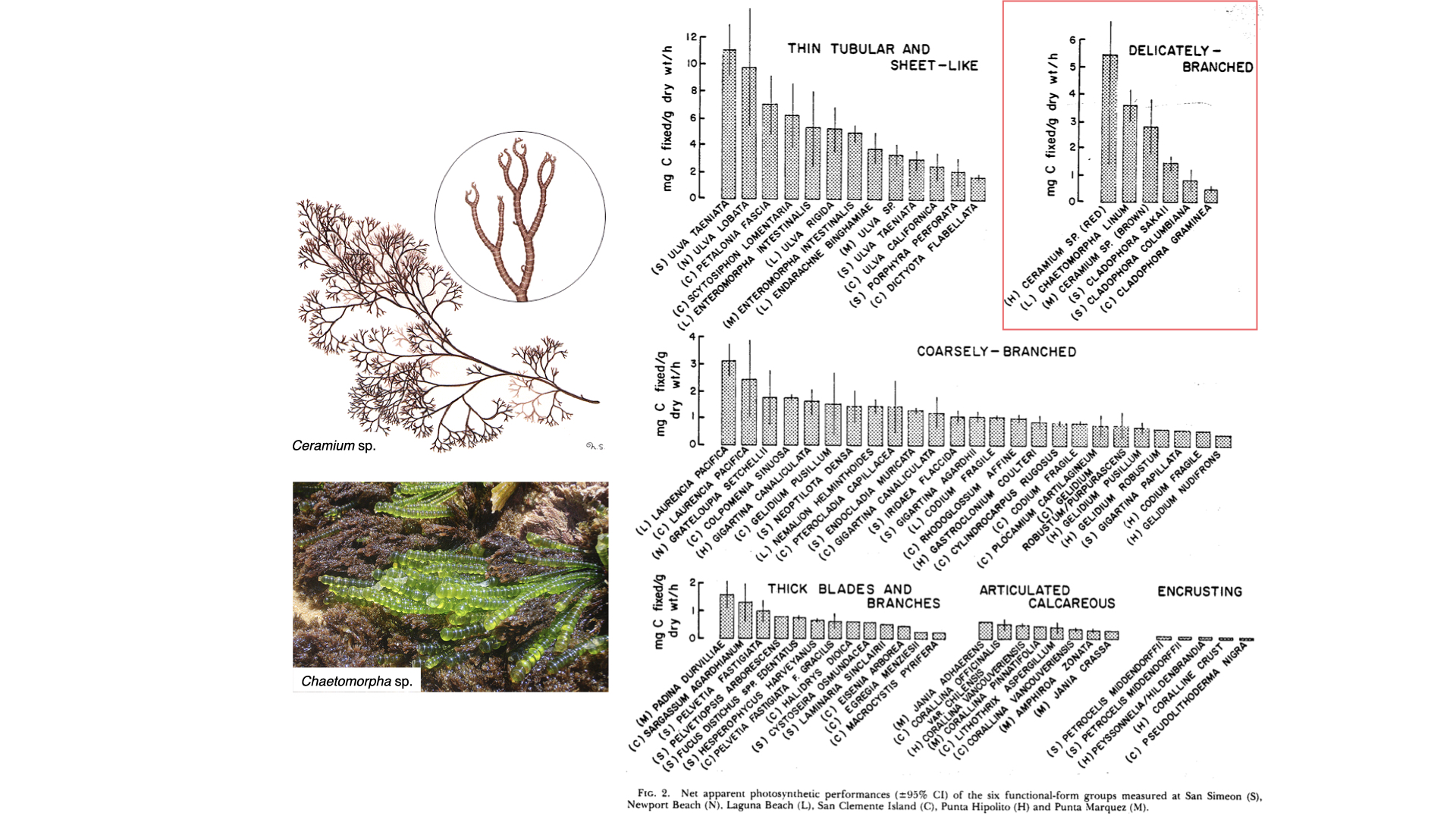

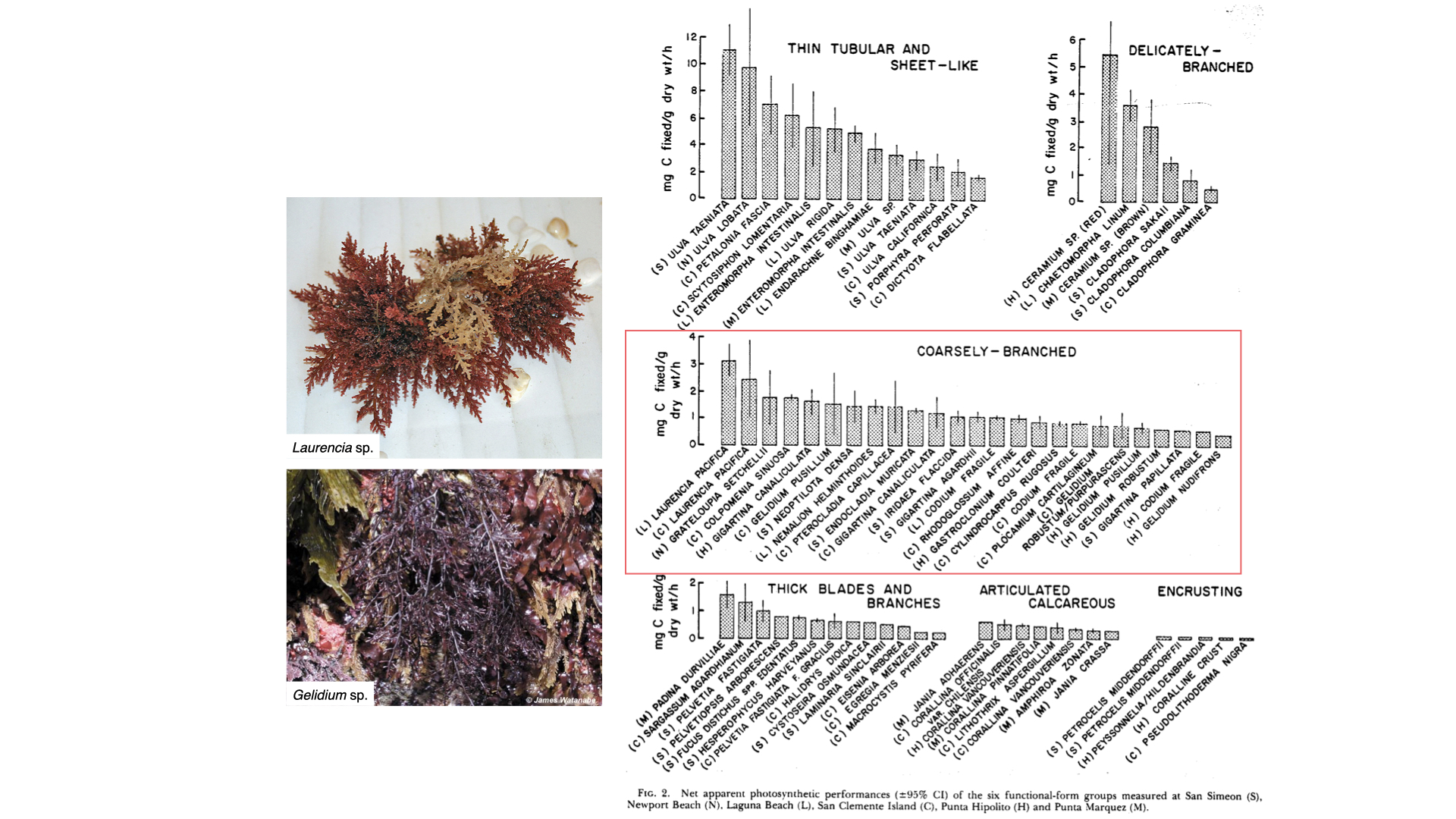

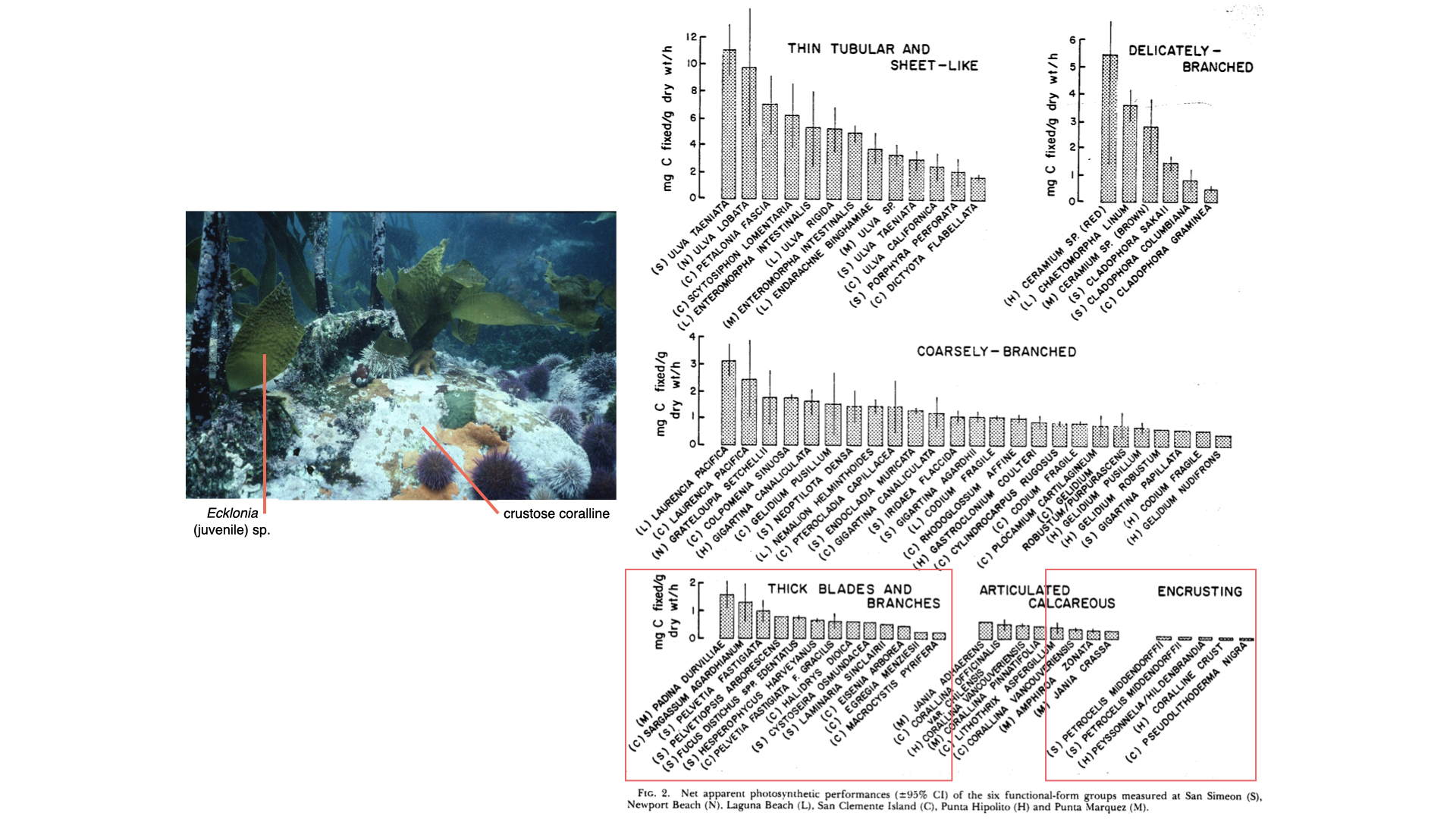

There were about six groups of functional forms. At one extreme are very thin, sheet-like forms — think of a lettuce, like cos lettuce. In fact, one seaweed they studied is called sea lettuce — Ulva is the common name because it has a similar appearance. As the seaweeds become increasingly complex, like filamentous or coarsely branched groups, the internal bulk increases and the surface area relative to bulk decreases. So, going from sheet-like at the top of the table to crustose at the bottom, you see a decrease in surface area to volume ratio as complexity increases.

We can look at some examples. Sea lettuce (Ulva) looks very similar to lettuce, and Porphyra umbilicalis — Porphyra is the seaweed used to make nori for sushi, commonly seen in Asian foods [note: Porphyra is now called Pyropia. Ulva and Porphyra are examples of the thin tubular and sheet-like group — characterised by high surface area to volume ratios. There is much more surface compared to the bulk inside.

If you look at the measurement of photosynthesis — the rate of carbon fixation, so milligrams of carbon per gram dry mass per hour — you will see that the values for these groups extend to quite high ranges, with high averages around 5 or 6 mg C/g dry mass/hour. For more complex forms — delicately branched, coarsely branched — the average value is lower, and as you move to even more complex functional forms, the photosynthetic efficiency decreases. This is because surface area to volume ratio declines — less surface area is available to capture carbon and exchange with the environment, thus constraining the rate of photosynthesis.

So, as surface area to volume ratio decreases, the ability of the plant to harvest enough carbon for fast growth rates also decreases. In simple seaweeds, plenty of surface area means efficient carbon access for the one or two cell layers, but in complex forms, there is less exchange and more constraints.

6.2 Broader consequences and applications

This constraint acts not only on carbon dioxide uptake and photosynthesis, but also on oxygen release, water and nutrient uptake, metabolic wastes disposal, and so on. The same principle applies to terrestrial plants.

7 Surface Area to Volume Ratio in Seagrasses

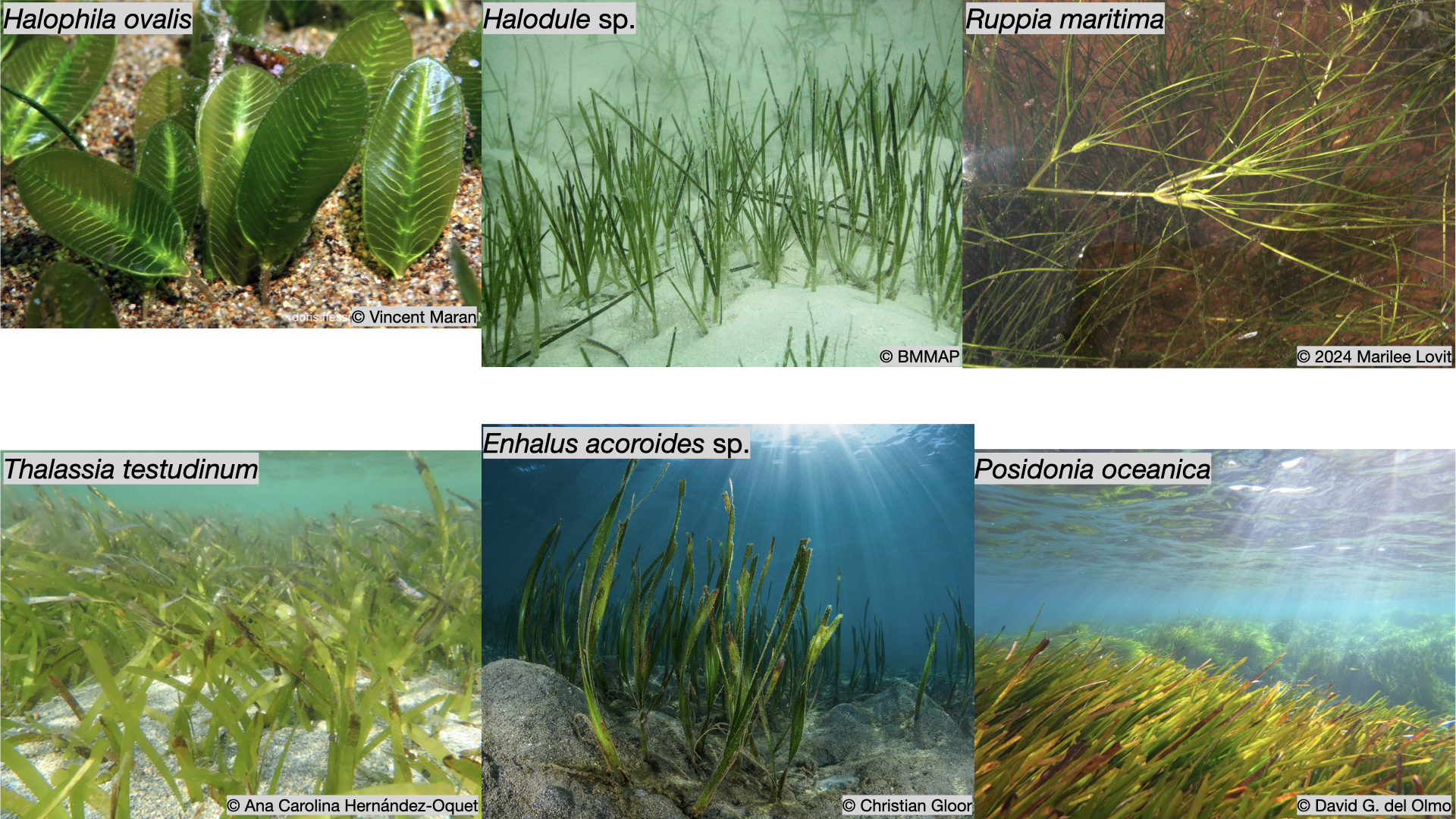

Now, let us extend this analysis to seagrasses. Seagrasses are, of course, angiosperms. They are different from true grasses but have evolved from land plants to reoccupy marine spaces. If you dive in seagrass meadows, for instance in Australia where these are abundant, it looks like a lawn of grass underwater. These meadows are often dominated by one or a few seagrass species.

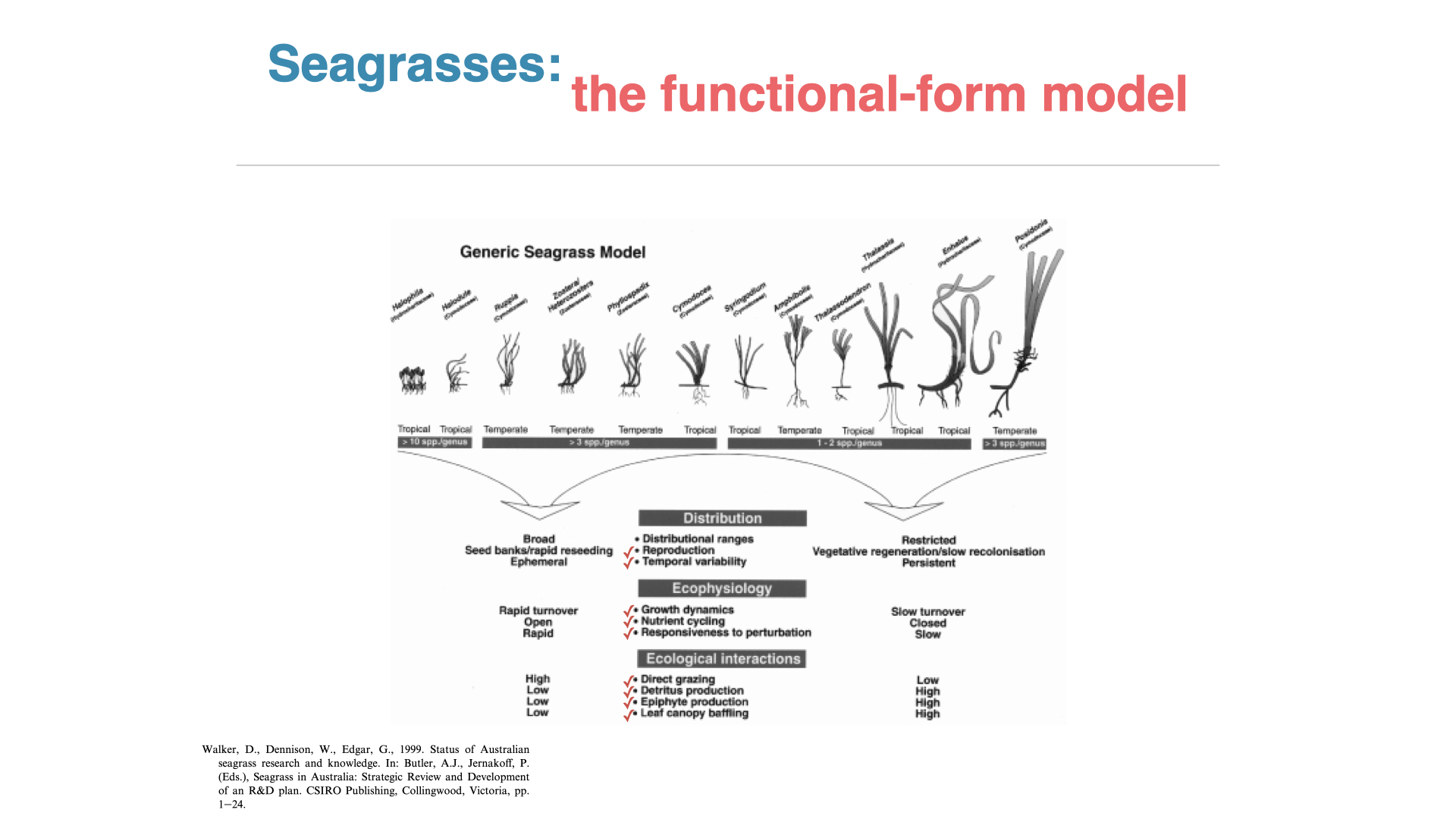

Seagrasses display a spectrum from very simple to very complex. On the left, we have fast-growing Halophila (high surface area to volume ratio); on the right, we have larger, more complex forms like Thalassia and Posidonia (low surface area to volume ratio). As you move from simple to complex, different evolutionary and ecological outcomes appear.

On the left (high surface area to volume ratio), seagrasses are ephemeral, growing quickly during favourable seasons, but they are fragile and highly accessible to grazing. That means that almost all the material is consumed quickly, with little left over as detritus, and they do not stick around long enough for epiphytes to colonise. The consequence is a rapid turnover and open nutrient cycling; any unfavourable environmental change has rapid impacts on these plants.

On the right (low surface area to volume ratio), species like Posidonia and Thalassia are persistent, long-lived, often surviving for many decades. They invest more energy into below-ground rhizomes for persistence, less into seeds. Nutrient and carbon turnover is slow — nutrients taken up are stored and remobilised when needed— and so they show a closed nutrient cycling strategy. They are resilient to many perturbations, but, if damaged, recover slowly.

In terms of ecological interactions, simple, ephemeral seagrasses are readily grazed; complex, persistent ones are tougher, less palatable. In complex forms, large amounts of detrital material can accumulate, resisting decomposition for long periods, and their persistence creates stable habitats, allowing rich communities of epiphytes, plants, and animals. The longer the structural tissues, such as rhizomes, remain, the more they can accumulate attached organisms.

8 Closing Remarks

Surface area to volume ratio, then, has major consequences for the ecophysiology, distribution, and ecological interactions of plants and algae. Whether you look at terrestrial or marine environments, you will see similar patterns: ephemeral, R-selected versus perennial, K-selected strategies. When you walk through nature, look for these surface area to volume ratio reasons for why different plants occupy particular habitats — often, the explanation lies in this fundamental geometric constraint.

There are some readings on ICOMVA for you, including some papers on surface area and volume ratios, as well as background on what seagrasses are. Remember, seagrasses are not true grasses; they look like grasses but represent a group of plants that have evolved on land and then returned to the sea — a separate evolutionary trajectory from seaweeds, which have always existed in the oceans. [Slide reference: left-hand side — Halophila as high surface area to volume, right-hand side — Posidonia sinuosa as low surface area to volume ratio. Note the presence of epiphytes on the latter.]

So, review this material, understand the consequences of surface area to volume differences, and their impacts across the spectrum of plant types and ecological circumstances. Be able to explain the consequences for distribution, ecophysiology, and ecological interactions.

Reuse

Citation

@online{smit,_a._j.,

author = {Smit, A. J.,},

title = {Lecture 2: {Surface} {Area} to {Volume} {(SA:V)} {Ratio}},

url = {http://tangledbank.netlify.app/BDC223/L02-SA_V.html},

langid = {en}

}