Lab 1: Surface Area to Volume (SA/V) Ratios in Biology

- Slides: SA:V

- Reading: Lecture 2. Surface Area to Volume (SA/V) Ratios in Biology

- Lab Date: 16 September 2024 (Monday)

- Due Date: 7:00, 23 September 2024 (Monday)

- Barrett, D. 1983. Body size and temperature: an extended approach. J. Biol. Educ. 71:78.

- Cohen, A, AB Moreh, R Chayoth. 1999. Hands-on method for teaching the concept of the ratio between surface area & volume. The American Biology Teacher 61: 691-696.

- Diamond, Jared. 1989. How cats survive falls from New York skyscrapers. Natural History, August, pp 20-26.

- Haldane, J.B.S. 1928. On Being the Right Size.

- Stanek, Jr., J. A. (1983) Why don’t cells grow larger? American Biology Teacher 45:393-395.

Students will work as individuals; assignments are per individual. This lab is due on Monday 23 September 2024 at 7:00 on iKamva.

Pre-Lab

Read this lab, the associated reading in the box above, and the pertinent material in your text.

Post-Lab

Upon completion of this lab:

- transcribe all tables and questions (Exercises A-E) to an electronic document and submit on iKamva. To submit online on Monday 23 September 2024 at 7:00.

Objectives

Upon completion of these exercises, the student will be able to:

- describe how organismal surface area and volume act together to influence S/V;

- perform various calculations involving surface are and volume;

- understand the relationship between S/V to biological form and ‘function’;

- understand how S/V relates to various rate processes in plants.

Background

These exercises are designed to introduce you to the concept of surface-to-volume ratios (S/V) and their importance in plant biology. S/V refers to the amount of surface a structure has relative to its volume (bulk). To calculate the S/V, simply divide the surface area by the volume. We will first examine the effect of size, shape, flattening an object, elongating an object on S/V ratios.

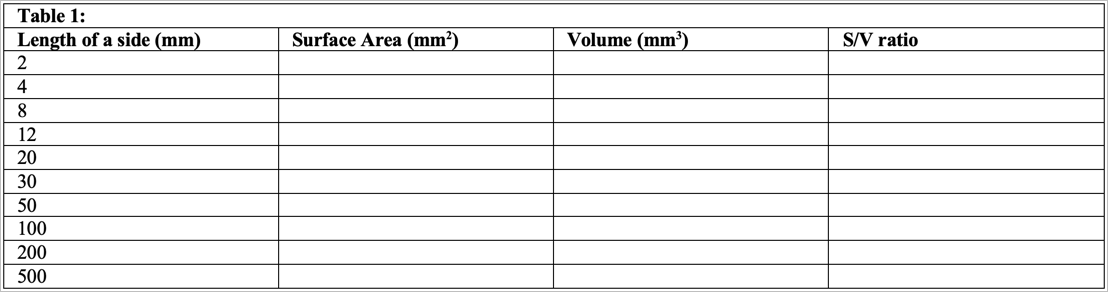

Exercise A: Influence of Size on S/V

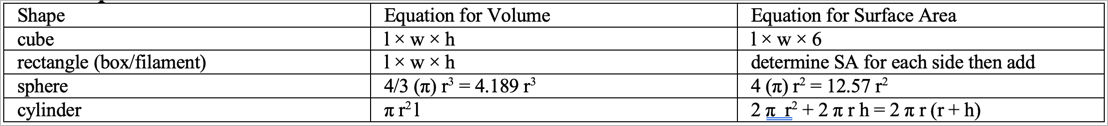

The purpose of this exercise is to see how the S/V changes as an object gets larger. We will use a cube to serve as a model cell (or organism). Cubes are especially convenient because surface area (length × width × number of sides) and volume (length × width × height) calculations are easy to perform. To calculate the S/V divide the surface area by the volume. Complete the table below for a series of cubes of varying size:

Questions

- Which cube has the greatest surface area? Volume? S/V?

- What happens to the surface area as the cubes get larger? What happens to the volume as the cubes get larger? What happens to the S/V as the cubes get larger?

- Proportionately, which grows faster – surface area or volume? Explain.

- Which cube has the most surface area in proportion to its volume?

- If you cut a cube in half, how does the volume, surface area and S/V of one of the resultant halves compare to the original?

- As the linear dimension of the cube triples, the surface area increases by the [square or cube?] of the linear dimension, and the volume increases by the [square or cube?] of the linear dimension.

- Plot the following: S/V vs cube size (length in mm); volume vs cube size (length in mm); and surface area vs cube size (length in mm).

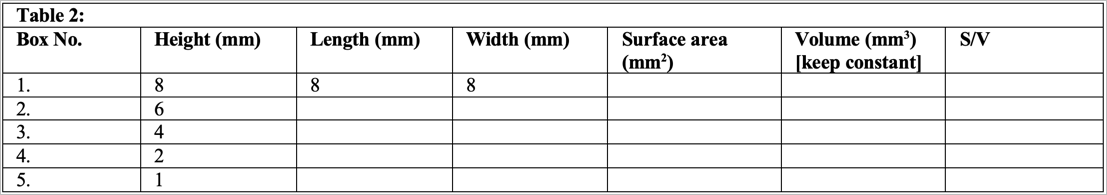

Exercise B: S/V Ratios in Flattened Objects

In this exercise we will explore how flattening an object impacts S/V. Consider a cube that is 8 × 8 × 8 mm on a side. Then, imagine that we can flatten the cube making it thinner and thinner (i.e. along one dimension, e.g. height) while maintaining the original volume. Complete the table below:

Questions

- What happens to the surface area and S/V as the box is flattened?

- Explain why some leaves are thin and flat (greater S/V). What could be the biological significance of this S/V relationship? Write a short essay to elaborate and include a few examples.

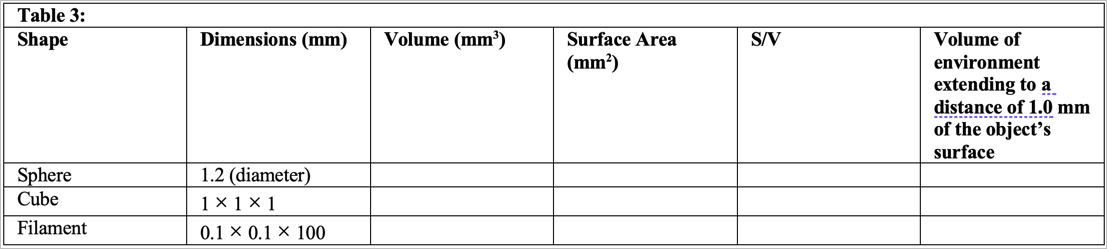

Exercise C: Shape and S/V Ratios

Here we will explore the impact of shape on surface to volume ratios. The three shapes given below have approximately the same volume. For each, calculate the volume, surface area and S/V and complete the table. The last column in the table, “Volume of environment extending to a distance of 1.0 mm of the object’s surface” is particularly important. Since the materials that an organism exchanges with its environment comes from its immediate surroundings, the greater this volume, the more material that can be exchanged.

Questions

- Make a sketch, to scale, of the three objects.

- Which shape has the greatest surface area? Volume? S/V?

- If you had to select a package with the greatest volume and smallest surface area, what shape would it be?

- Explain the implications of the last column in the table.

Exercise D: Shape and S/V Ratios (continue)

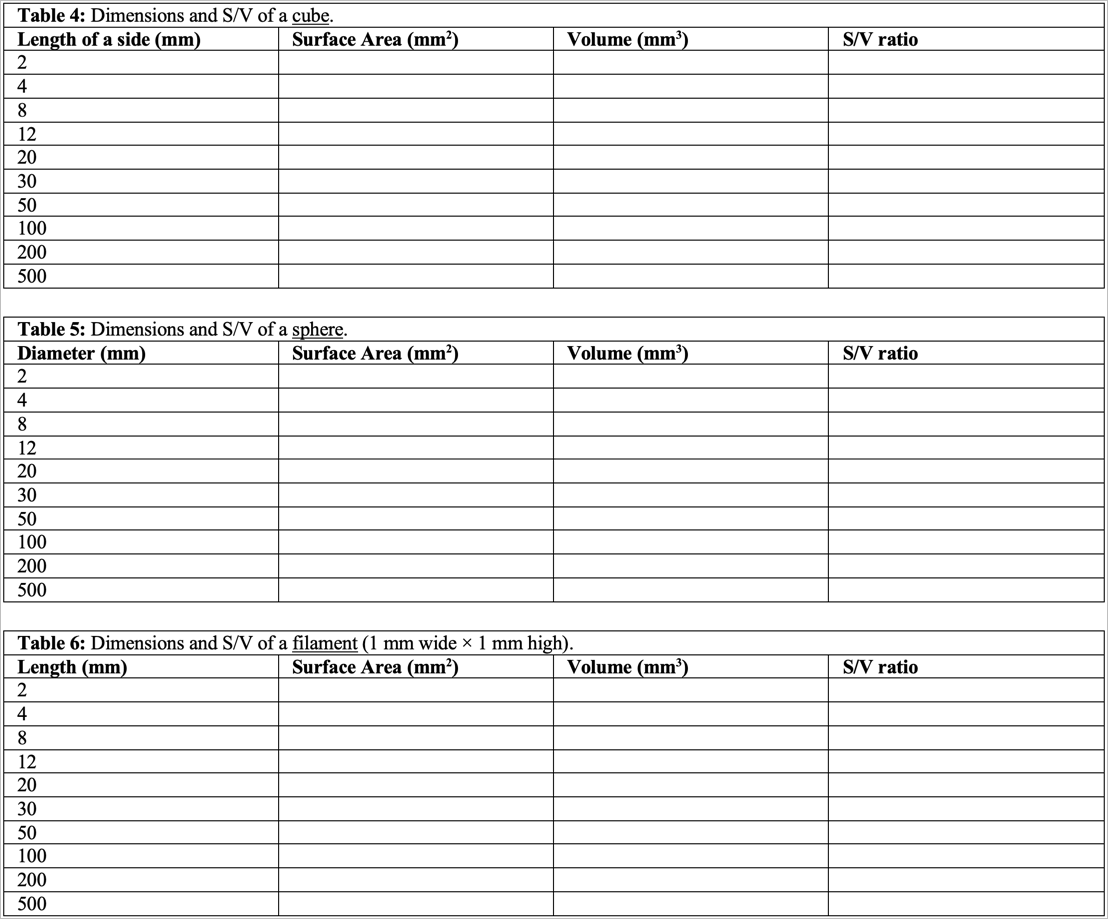

Complete the following tables (4-6), and for the data in each table, produce independent graphs of length (or diameter) vs surface area, length (or diameter) vs volume, surface area vs volume, and length (or diameter) vs S/V (i.e. there would be 12 figures in total).

Explain the relationships in the table regarding metabolic efficiency, and define what this efficiency might entail and why it is crucial. Name representative groups of organisms that filamentous and spherical morphologies can characterise, and considering the metabolic ‘functioning’ of these groups, explain why their particular shapes matter.

Exercise E: Other Plant Applications

Questions

- Explain why plants are essentially a cluster of filaments, whereas animals are blobs. In other words, why is a thin, elongated rectangle a good model for a plant, but a sphere a good model for an animal?

- Explain how S/V ratios relate to the form of plants that have evolved in mesic (moderate), xeric (dry) and hydric (aquatic) environments.

- Explain why the cells of the spongy mesophyll layer are irregular in shape whereas those of the palisade layer are more rectangular.

- Describe the trends that have occurred in S/V during the evolution of plants from single cellular cyanobacteria to multicellular algae to mosses to ferns to angiosperms.

- Obtain the leaf of a mesophytic plant. Record the scientific name and family of this species. Calculate the surface area of the leaf (ignore the edges of the leaf). Then, calculate the dimension of a cube that would have the same surface area.

- Explain why cells divide when they get large.

- Explain why the rate of cell growth slows as cells get larger.

- Explain why cats can fall off of tall buildings and survive. Why do people splat?

- Describe the scientific inaccuracy in the story of Goldilocks and the porridge.

- Explain why lungs, gills and intestines have the shape they do.

- Describe and explain the shape of a radiator?

- Mice have large eyes relative to size, and elephant small ones. Explain why. Are large eyes better than small ones?

- Earth is geologically active (has a molten core; plate tectonics) but the moon is apparently no longer geologically active. Explain why using S/V.

- Shrews have a reputation for being ferocious eaters. In other words, they must feed constantly. Explain why.

- Why are there few small animals in the Arctic?

Useful equations

Reuse

Citation

@online{smit,_a._j.,

author = {Smit, A. J.,},

title = {Lab 1: {Surface} {Area} to {Volume} {(SA/V)} {Ratios} in

{Biology}},

url = {http://tangledbank.netlify.app/BDC223/Lab1_SA_V.html},

langid = {en}

}